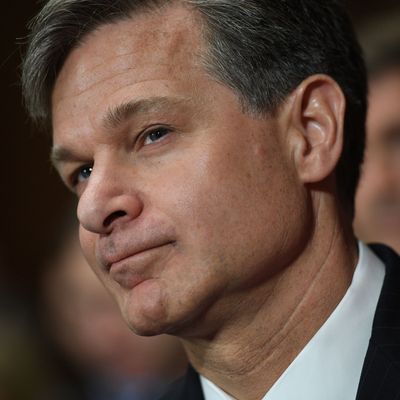

News reports from likely future FBI director Chris Wray’s Senate hearing today focused on the question of the agency’s independence from the White House. This is understandable — the bureau’s relationship to the White House is at the top of everyone’s mind — and Wray performed well: “My commitment is to the rule of law, to the Constitution,” he told members of the Senate Judiciary Committee. But when it came to the less attention-getting, but no less important, question of encryption, unfortunately, Wray performed somewhat less inspiringly: “There’s a balance, obviously, that has to be struck between the importance of encryption — which we can all respect when there are so many threats to our systems — and the importance of giving law enforcement the tools that they lawfully need to keep us all safe,” he said.

The problem is that there isn’t really a legal balance to be struck when it comes to encryption. American tech companies already comply with lawful orders for user information that isn’t fully encrypted, and shy of building backdoors into their products, there isn’t a lot more they can do.

“Unfortunately, I’m still not sure how this is an issue that can be solved by working together with industry,” said Matthew Green, a renowned cryptography professor at Johns Hopkins University, after seeing Wray’s comments. “Either the U.S. government will pursue a strategy that includes mandated encryption backdoors or it won’t. I believe other forms of cooperation, such as metadata sharing, are already available.”

Wray is entering a decades-long debate, one where a principal argument hasn’t really changed: Should you be allowed to make a device or a method of communication that’s so secure, even you have no way of knowing what your users are doing or saying? The FBI, famously, was so stumped when it couldn’t access San Bernardino shooter Syed Farook’s iPhone last year that it invoked the All Writs Act of 1789, a broadly written law used when the government needs an authorization that Congress hasn’t yet legislated or thought of, and demanded Apple write a personalized, fake software update to get past the phone’s login screen. At the 11th hour, the FBI said it had found and paid for a rare vulnerability in the code for the 5c, the model Farook had, and stood down.

Technologists and cryptographers have long been unanimous that forcing a tech company to build a secret vulnerability into their products, only to be used for emergency situations — a backdoor — is a terrible idea. If cops can use it, hackers and foreign governments can probably find it and exploit users, for one thing. And if American companies would be forced by law to build backdoors, as floated in an ill-fated draft bill last year by senators sympathetic to the FBI’s concerns about terrorists “going dark,” privacy-minded consumers would simply start using secure messaging apps made in countries that didn’t have that law.

At the same time, it’s hard to tell the law-and-order crowd that if a terrorist cell in the U.S. is using Signal, the FBI has to simply throw up its hands and use whatever other investigative tools are at its disposal. That’s why a number of political figures, among them former Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton and former FBI Director James Comey, have rejected the idea of outright backdoors, but like Wray today, still declared a wistful support for some kind of “compromise” solution, achievable by the tech industry and federal government really putting their heads together.

But politicians and law-enforcement figures pushing for a compromise “ignore the realities of mathematics and the dire need to increase internet security in favor of pushing technologists to ‘nerd harder’ and come up with some magical way to create strong security tools that only the FBI could break,” said Amie Stepanovich, U.S. policy manager at Access Now, a group that advocates for digital civil liberties.

In Wray’s defense, maybe he only hoped for an impossible compromise because he hasn’t had time to give the issue much thought: He readily admitted he was an “outsider” who didn’t have enough information about encryption in front of him to present a formal plan, a repeated theme in his hearing. For the future, Wray might consider stressing that pushing for mandatory backdoors should be off the table, or that strong encryption should be a fundamental consumer protection in a world where Russian intelligence agencies target American civilians, like the heads of U.S. presidential campaigns. Wray could have said that agents stymied by locked phones would have to rely more on old-school investigative techniques. He could have admitted that while the gray market of buying exploits in emergencies is far from perfect, it’s worked so far, and there simply isn’t a better solution out there.

Unfortunately, no senator probed Wray much further on the issue. What does he think the FBI should do if the agency encounters another Farook iPhone case, but this time can’t find a vendor hawking exploits? Apparently, hope that math changes.