Page controls

Page content

Approved by the OHRC: November 2018

View PDF: A Collective Impact: Interim report on the inquiry into racial profiling and racial discrimination of Black persons by the Toronto Police Service

Contents

Executive summary

I. Introduction

II. Background and context

III. Progress of the inquiry

IV. Findings

V. Areas of concern

VI. Interim actions

VII. Next steps

Appendix A: Timeline

Appendix B: Terms of reference

Appendix C: Inquiry letters

Appendix D: Status of OHRC requests

Appendix E: Wortley Report

Endnotes

Executive summary

Between 2013 and 2017, a Black person in Toronto was nearly 20 times more likely than a White person to be involved in a fatal shooting by the Toronto Police Service (TPS). Despite making up only 8.8% of Toronto’s population, data obtained by the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) from the Special Investigations Unit (SIU) shows that Black people were over-represented in use of force cases (28.8%), shootings (36%), deadly encounters (61.5%) and fatal shootings (70%). Black men make up 4.1% of Toronto’s population, yet were complainants in a quarter of SIU cases alleging sexual assault by TPS officers.

SIU Director’s Reports reveal a lack of legal basis for police stopping or detaining Black civilians in the first place; inappropriate or unjustified searches during encounters; and unnecessary charges or arrests. The information analyzed by the OHRC also raises broader concerns about officer misconduct, transparency and accountability. Courts and arms-length oversight bodies have found that TPS officers have sometimes provided biased and untrustworthy testimony, have inappropriately tried to stop the recording of incidents and/or have failed to cooperate with the SIU.

The OHRC spoke directly to approximately 130 individuals in Black communities. It heard first-hand about their experiences with the TPS and the resulting fear, trauma, humiliation, mistrust and expectations of negative treatment by police. Even where individuals did not have first-hand experiences, high profile incidents or experiences of friends and family reinforced community distrust. For example, one individual observed:

The Dafonte Miller matter affects everyone in the community because it was so egregious and it was hidden and was allowed to be hidden for so long until someone else brought it forward… [it] is a collective experience…someone in your family has experienced some sort of trauma with the police – so it always brings you back to that event… it’s a collective impact…

Last year, the OHRC launched its inquiry into racial profiling and racial discrimination of Black persons by the TPS to help build trust between the police and Black communities. The goal of the inquiry was to pinpoint problem areas and make recommendations. This Interim Report describes what the OHRC has done to date. It provides findings relating to SIU investigations of police use of force resulting in serious injury or death, describes the lived experiences of Black individuals, and offers highlights of legal decisions.

The Interim Report findings go some way towards explaining why trust between the TPS and Black communities remains fractured, despite decades of protests, reports, recommendations and commitments related to anti-Black racism. It confirms the long-standing concern of Black communities that they are over-represented in incidents of serious injury and deadly force involving the TPS. It demonstrates that the more serious the police conduct and lethal the outcome, the greater the over-representation. It reveals serious use of force in interactions where there was a lack of a legal basis for police stops and/or detentions of Black civilians in the first place, and inappropriate or unjustified searches of Black civilians.

Building trust between police and the community should be a top priority for everyone, not just Toronto’s Black communities. There is a clear link between public confidence in policing and public safety. People are less likely to cooperate with police investigations and provide testimony in court if they have negative perceptions of police. Without trust, police cannot provide proactive, intelligence-based policing, and this has profound consequences for our justice system. It also has a significant impact on the cost effectiveness of Toronto police services which cost over one billion dollars annually.

In a city where over half the population identifies as “visible minorities,” one of the most effective ways for police to build trust is to respect human rights. Police must hold themselves to the same high standards that we expect of other public institutions. That is the essence of the rule of law. The TPS and Toronto Police Services Board (TPSB) must be proactive in fulfilling their obligations under Ontario’s Human Rights Code. They must take steps to both prevent and remedy racial discrimination, particularly when they are on notice that there may be a problem.

Overall, the OHRC has serious concerns about racial profiling and racial discrimination of Black people by the TPS in use of force incidents; stops, questioning and searches; and charges.

The TPS share some of these concerns. Nearly ten years ago, then-Chief Bill Blair acknowledged that racial bias exists within the TPS. Since then the TPS has made some efforts to “assess and address issues of racial profiling and bias in community engagements (at both the individual and systemic levels) to enable the delivery of bias-free police services.” In 2013, the TPS noted that “effectively addressing and eliminating bias in policing has arguably been one of the most challenging and important undertakings in the history of the Service.” The TPSB publicly supported the OHRC’s inquiry when it was publicly launched in November 2017.

Nearly a year into its inquiry, the OHRC is releasing an Interim Report outlining some of its findings, concerns, next steps and suggested actions. The Interim Report will inform Ontario’s ongoing consultations on policing and police oversight reform and encourage the TPS and TPSB to do more to address human rights issues.

The OHRC will continue its efforts to analyze data received from the TPS, TPSB and SIU, hear directly from diverse Black individuals, and determine whether and where other problem areas exist. The OHRC will release a final inquiry report with findings, recommendations and next steps.

In advance of the release of its Final Report, given the interim findings, the OHRC calls on:

- The TPS and TPSB to acknowledge that the racial disparities and community experiences outlined in this Interim Report raise serious concerns.

- The TPS and TPSB to continue to support the OHRC’s inquiry into racial profiling and racial discrimination of Black persons.

- The TPSB to require the TPS to collect and publicly report on race-based data on all stops, searches, and use of force incidents.

- Ontario to implement recommendations in the Report of the Independent Police Oversight Review.

- The City of Toronto to implement recommendations in the Toronto Action Plan to Confront Anti-Black Racism.

I. Introduction

In 1988, Lester Donaldson, a Black man diagnosed with schizophrenia, was shot and killed in his rooming house by a Toronto Police Service (TPS) officer. The police said they were responding to a call of a man holding hostages, but found Mr. Donaldson alone in his room. He was shot for allegedly lunging at the officer with a knife. The officer was charged with manslaughter, but was later acquitted.[1]

The Black Action Defense Committee was formed in the wake of Mr. Donaldson’s death and 600 people demonstrated in front of 13 Division where the officer worked. Mr. Donaldson’s death contributed to the establishment of the SIU in 1990.[2]

Since this time, numerous task forces, studies, inquiries, and Court and tribunal decisions have confirmed that there is anti-Black racism in policing.[3]

The TPS itself has acknowledged that racial bias exists within the TPS.[4] The City of Toronto has stated that “Black Torontonians face many disparities related to law enforcement”[5] and “they are disproportionately impacted by racial profiling and over-policing.”[6] Mayor Tory has recently acknowledged that “…more work is still needed to examine how we can improve police services, policies and procedures that contribute to discrimination and racial profiling.”[7]

Despite these reviews, recommendations, decisions and acknowledgments, concerns with racial discrimination against Black people and police accountability have persisted and were exacerbated by the 2015 death of Andrew Loku.

Concerns of Black communities[8] led the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) to start an inquiry into racial profiling and racial discrimination of Black persons by the TPS. This inquiry is focused on particular activities between January 1, 2010 and June 30, 2017, to determine their impact on Black communities, including: stop and question practices; use of force; arrests and charges and forms and conditions of release for various offence categories.[9]

The inquiry will also examine the TPS and Toronto Police Service Board’s (TPSB) culture, training, policies, procedures and accountability mechanisms relating to racial profiling and racial discrimination.

This inquiry is different from past initiatives by the OHRC and others because it combines the lived experiences of Black communities with analysis of documents and data that the OHRC has been able to obtain through its inquiry powers under s. 31 of the Ontario Human Rights Code (the Code).[10]

Its goal is to pinpoint problem areas and make strong recommendations, which, if properly implemented, will set the stage to build trust between Black communities and police. Trust is the foundation to building relationships, and as the TPS has recognized, relationships are the key to strong and effective policing.

The OHRC’s inquiry is ongoing and there is more work to do over the coming months. It needs to analyze documents and data provided by the TPS, further analyze the data of the Special Investigations Unit (SIU), and continue outreach to Black communities. The OHRC will also assess if it should take further steps under the Code to address any issues identified.

This interim report is the first step towards the OHRC’s ultimate goal. It describes what the OHRC has done to date. It provides findings relating to SIU investigations of police use of force resulting in serious injury or death, describes the lived experiences Black communities have shared during the OHRC’s community engagement, and offers a review of legal decisions. The OHRC has spoken to approximately 130 individuals in Black communities across Toronto.

The interim report on the work and findings to date shows that there are deeply concerning racial disparities in use of force incidents that result in serious injury or death. It confirms the long-standing concern of Black communities that they are over-represented in incidents of serious injury and deadly force involving the TPS. It demonstrates that the more serious the police conduct and lethal the outcome, the greater that over-representation. It reveals serious use of force in interactions where there was a lack of a legal basis for police stops and/or detentions of Black civilians in the first place, and inappropriate or unjustified searches of Black civilians. It also highlights the SIU’s concerns about TPS co-operation with the SIU.

These racial differences and concerns call for an explanation by the TPS and TPSB, one that goes beyond simply relying on the fact that the SIU did not lay criminal charges. The TPS and TPSB also need to take steps to proactively address the impact this reality has on the trust and confidence that Black communities have in law enforcement in Canada’s largest and most diverse city. The results to date also underscore the need to move forward with measures to improve police oversight and accountability.

II. Background and context

a) The OHRC’s work on racism in policing

State action, including policing, is subject to the rule of law. The Code is part of the rule of law and promotes individual human rights and dignity. The Code prohibits discrimination against people based on race, ancestry, colour, creed, place of origin and ethnic origin, among other grounds, in policing services.[11] Racial profiling[12] and racial discrimination against Black people can be based on one or more of these grounds. Courts and tribunals have repeatedly recognized that racial profiling is a systemic problem in policing.[13]

There is also a socially significant intersection between race and mental health that may affect officer decisions about use of force. There are stereotypes about Black people regarding violence and criminality, and concerns that police are more likely to use force in their interactions with Black people. Furthermore, people with mental health disabilities may be more likely to be subject to officer use of force because of responses to police instructions or behaviours that may seem unusual, unpredictable or inappropriate, or due to police reliance on stereotypical assumptions about dangerousness or violence.[14]

The OHRC’s mission is to promote and enforce human rights, engage in relationships that embody the principles of dignity and respect, and create a culture of human rights compliance and accountability. The OHRC accomplishes its mission by exposing and challenging systemic discrimination, and examining incidents or conditions of tension or conflict from a human rights perspective, through education, policy development, public inquiries and litigation.[15] The OHRC’s public inquiry powers under s. 31 of the Code include but are not limited to:

- The power to request the production of documents or things

- The power to question a person on matters that may be relevant to the inquiry

- The ability to use expert assistance to carry out the inquiry.

Combatting racial discrimination in policing, including racial profiling, has been at the core of the OHRC’s work for over 15 years. The OHRC has created resources to help police services identify, monitor and reduce racial discrimination, including guides to collecting human rights-based data and creating organizational change; Paying the Price, the OHRC’s 2003 report on its inquiry into the effects of racial profiling; and Under suspicion, the OHRC’s 2017 research and consultation report on racial profiling that will shape its forthcoming policy and guidelines on racial profiling.[16] The OHRC has also made submissions to the government and independent reviewers outlining the need for changes in laws to promote accountability for systemic discrimination in policing, address carding and make communities safer.[17]

The OHRC has worked directly with the TPS and TPSB on issues of discrimination. In 2007, the OHRC entered into a three-year Human Rights Project Charter with the TPS and TPSB which aimed to embed human rights in all aspects of police operations.[18] But, as the OHRC did not have control over developing, prioritizing or implementing the recommendations, the Project Charter failed to enhance independent monitoring or accountability for systemic racial discrimination.

The OHRC was also involved with the TPS throughout various stages of the Police and Community Engagement Review (PACER) which began in 2012 and which led to a Report in 2013 that identified 31 Recommendations intended to ensure fair and bias free policing.[19] Upon the release of the report in 2013, the OHRC participated on a community consultation committee to support implementation of the report’s recommendations, and provided direct input into specific initiatives that emerged from the implementation activity. OHRC’s participation on the committee continued until 2018.

The OHRC has also made deputations urging the TPSB to address racial discrimination.[20] Finally, the OHRC has been engaged in litigation challenging racial discrimination by the TPS.[21]

Two years ago, the OHRC attempted to intervene at the Toronto Police Service Disciplinary Tribunal in the “Neptune 4” matter to ensure that racial profiling would be addressed. An Office of the Independent Police Review Director (OIPRD) complaint was filed after four Black teens were arrested at gunpoint by two TPS officers in 2011; their charges were later withdrawn. The encounter was caught on Toronto Community Housing Corporation security cameras. A version posted by the Toronto Star shows one of the teens being punched and pulled to the ground. The OIPRD found that charges of officer misconduct were warranted. The OIPRD highlighted that, according to the officers and the youth, the youth “were not misbehaving in any manner.” The OHRC was denied leave to intervene on jurisdictional grounds.[22]

b) Toronto’s Black population

According to the 2016 Census, the population of Toronto was 2,731,571. “Visible minorities” made up 51.5% of population. The largest “visible minority” groups were South Asian, Chinese and Black, who made up 12.6%, 11.1% and 8.8% of the population respectively.[23] There were 239,850 Black people in Toronto.[24]

c) Recent concerns about anti-Black racism in policing in Toronto[25]

In 2015, Andrew Loku, a Black man who lived in an apartment complex with units leased by the Canadian Mental Health Association, was shot and killed by a TPS officer. According to the SIU, he was shot seconds after the officer saw Mr. Loku holding a hammer in the hallway of the building.[26]

Black Lives Matter Toronto organized protests outside of TPS headquarters and at Queen’s Park in March and April of 2016, challenging racially biased policing and calling for an inquest into the death of Mr. Loku after the SIU did not find grounds to lay criminal charges against the officer.[27] Mr. Loku’s death contributed to the appointment of the Honourable Michael H. Tulloch, a judge of the Court of Appeal for Ontario, to review and make recommendations related to police oversight in Ontario.[28]

In 2015, the OHRC conducted a survey based on a non-random sample and gathered 1,503 responses from across Ontario. The results were published in Under Suspicion and most survey respondents came from the Toronto and Central region of Ontario.[29] 25.9% of Black respondents reported being stopped and questioned by police and having information recorded “unconnected to any specific traffic violation, criminal investigation or specific suspect description.”[30] Of the survey respondents who reported being racially profiled six or more times in the last 12 months, and reported being racially profiled by police, almost half (21) were Black. [31]

The OHRC also heard that some people may be exposed to racial profiling based on their unique intersection of identities. For example, Black male youth may be more likely to be singled out repeatedly by police because of stereotypes about being involved with crime.

Truthfully all my friends have been through the same things I have been through. It has become second nature to be aware of the police... [It’s a] clear violation, but position of power leaves us to just accept this treatment as normal (Black male, age 20-24).[32]

In 2017, the Environics Institute for Survey Research, in partnership with the United Way of Toronto and York Region, the YMCA of Greater Toronto, and Ryerson’s Diversity Institute released the Black Experience Project, a study of the Greater Toronto Area’s Black community. The study sample was based on 1,504 interviews of people who identified as Black or of African heritage. The project raised significant concerns about anti-Black racism in policing. For example, of Black men aged 25 – 44 who were interviewed, 60% reported being harassed or treated rudely by the police, and 79% reported being stopped in public places by the police.[33]

d) Policing and police oversight in Toronto

Toronto Police Service and Chief of Police

The duties of police services in Ontario, including the TPS, are set out in the Police Services Act.[34] They include preventing crime, enforcing laws and responding to emergencies.[35] The HRTO and the Court of Appeal for Ontario have held that these duties also include respecting human rights and complying with the Code, for example by not engaging in racial discrimination in delivering police services.[36]

The Chief of Police oversees the operation of the police service in accordance with the Police Services Act as well as the objectives, priorities and polices established by the Toronto Police Services Board (TPSB). The Chief reports to the TPSB and must obey its lawful orders and directions.[37]

The TPS is the largest municipal police service in Canada and employs over 5,500 officers and more than 2,200 civilian staff.[38] It has a 2018 budget of 1.005 billion dollars.[39]

Mark Saunders has been the Chief of the TPS since 2015. The Honourable Bill Blair was the Chief of the TPS between 2005 and 2015.

In 2009, then-Chief Blair acknowledged that racial bias exists within the Toronto Police.[40] A goal of TPS’s 2013 Police and Community Engagement Review (PACER) Report was to “assess and address issues of racial profiling and bias in community engagements (at both the individual and systemic levels) to enable the delivery of bias-free police services.” The report further stated that “effectively addressing and eliminating bias in policing has arguably been one of the most challenging and important undertakings in the history of the Service.”[41]

The OHRC acknowledges that the TPS has implemented a number of initiatives between January 1, 2010 to June 30, 2017 to address racial discrimination and racial profiling of Black people, including PACER. The OHRC will analyze these initiatives in its final report.

Toronto Police Services Board

The TPSB is a civilian board that oversees how policing is provided in Toronto. It is responsible for the “provision of adequate and effective police services.” It has the authority to set objectives and priorities, establish policies for the effective management of the police force, and direct the Chief of Police and monitor his performance. [42]

Like police officers and the Chief, the TPSB is required to provide a service environment free of discrimination. The Chief and the TPSB are jointly liable for the discriminatory actions of TPS officers and have a joint responsibility for compliance with the Code.[43]

Dr. Alok Mukherjee was the Chair of the TPSB between 2005 and 2015. Andy Pringle has been the Chair of the TPSB since Dr. Mukherjee’s retirement in 2015. Mayor John Tory is also a member of the TPSB.

In 2016, the Transformation Task Force, co-chaired by Chief Saunders and Chair Pringle, acknowledged that as Toronto grows, it will continue to “face challenges related not only to crime and social disorder, but also…discrimination [and] systemic racism.”[44]

The OHRC recognizes that the TPSB has implemented a number of initiatives between January 1, 2010 to June 30, 2017 to address racial discrimination and racial profiling of Black people, including a Human Rights Policy. The OHRC will analyze these initiatives in its final report.

The City of Toronto

In 2017, Toronto City Council adopted[45] the Toronto Action Plan to Confront Anti-Black Racism. Mayor John Tory acknowledged that “[a]nti-Black racism exists in Toronto” and its elimination must be the City’s goal. The plan stated that “Black Torontonians face many disparities related to law enforcement” and “they are disproportionately impacted by racial profiling and over-policing.”[46]

Recommendations and actions in the plan include:[47]

- Implement measures to stop racial profiling and over-policing of Black Torontonians

- Review the decision not to destroy the previously collected carding data

- Review use of force protocols from an Anti-Black Racism Analysis

- Review police and community training, including Community Crisis Response Programs, to include use of force issues

- Strengthen protocols for police response to Emotionally Disturbed Persons (EDP) and report regularly on police-EDP interactions, using an Anti-Black Racism Analysis.

- Build a more transparent, accountable and effective police oversight system to better serve Black Torontonians and to strengthen community trust in police

- Mandate the collection and public reporting of race-based data for greater transparency

- Review and overhaul the Professional Standards for discipline at the Toronto Police Service

- Convene a Community and Police Eliminating Anti-Black Racism Team (CAPE-ABR Team) of community and police leaders as a resource to inform the development and implementation of actions related to policing and the justice system.

- Invest in alternative models that create better safety outcomes for Black Torontonians

- Work with community partners to build a coordinated strategy to advance police accountability and community capacity to respond to policing and the criminal justice system, including translation, expansion, and dissemination of “know your rights” information

- Use an Anti-Black Racism Analysis to develop and implement alternative models of policing that focus on community engagement.

The Special Investigations Unit

The SIU is a civilian body and arms-length agency of the Ministry of the Attorney General with jurisdiction extending to all police officers in Ontario. The SIU’s mandate is set out in the Police Services Act. Its mandate is to conduct investigations into the circumstances of serious injuries and deaths that may have resulted from criminal offences committed by police officers, including allegations of sexual assault. It has the power to investigate police officers and lay criminal charges if there are reasonable grounds to do so.[48]

“Serious injuries” are defined by the SIU as:

“Serious injuries” shall include those that are likely to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim and are more than merely transient or trifling in nature and will include serious injury resulting from sexual assault. “Serious Injury” shall initially be presumed when the victim is admitted to hospital, suffers a fracture to a limb, rib or vertebrae or to the skull, suffers burns to a major portion of the body or loses any portion of the body or suffers loss of vision or hearing, or alleges sexual assault.[49]

The SIU does not have a mandate to investigate discrimination or officer misconduct. The SIU does not have the authority to investigate alleged violations of the Code or other forms of improper conduct, make findings of discrimination, or lay disciplinary charges for officer misconduct that proceed to a disciplinary hearing.[50]

The Office of the Independent Police Review Director

The OIPRD oversees all public complaints about police in Ontario, and conducts systemic reviews related to public complaints.[51]

Discrimination under the Code is one form of misconduct that can give rise to a public complaint insofar as it is a subset of discreditable conduct.[52]

Independent Police Oversight Review and the Safer Ontario Act

In April of 2016, Justice Tulloch completed his Independent Police Oversight Review. This review provided a framework that would allow for better monitoring and accountability for systemic discrimination. He recommended that there be, among other things:[53]

- Demographic data collection by police oversight bodies

- Independent prosecution and adjudication of public complaints, with interventions by third parties

- The ability of the OIPRD to initiate investigations in the public interest, even if no complaint is filed

- The ability of the SIU to comment on and refer conduct matters to the OIPRD

- Mandatory social and cultural competency training for staff, developed and delivered in partnership with Indigenous and other community organizations

- Recruitment to ensure that staff and leadership more closely reflect the communities they serve

- SIU discretion to conduct an investigation into any criminal matter when such an investigation is in the public interest. When deciding whether an investigation is in the public interest, the SIU should consider, among other things, if the matter is potentially aggravated by systemic racism or discrimination.

He also made several recommendations that more broadly support the principles of transparency and accountability in police oversight, including that:[54]

- The general requirement of the duty to cooperate with the SIU, as well as the timing of that requirement, be set out in legislation

- The SIU release the director’s reports to the public in cases that do not result in a criminal charge

- The SIU release to the public the officer’s name, offence charged and timing of the charge, and details about the officer’s next court appearance in cases that result in a criminal charge.

The Ontario Special Investigations Unit Act, 2018,[55] Policing Oversight Act[56] and Safer Ontario Act[57] codified many of these recommendations.[58] After the provincial election in June 2018, the new Government put implementation of the new laws on hold pending further consultation with stakeholders. In August 2018, the OHRC provided a submission to the new government encouraging timely implementation of the legislative reforms.[59]

III. Progress of the inquiry

|

Activity |

Date |

|

OHRC Commissioners approve the inquiry |

March 2017 |

|

Retain Dr. Scot Wortley from the University of Toronto to provide expert assistance |

March 2017 |

|

Complete case-law review |

June 2017 |

|

Send inquiry letters to TPS, TPSB and SIU (see Appendix C) |

June 2017 |

|

Release of terms of reference (see Appendix B) |

November 2017 |

|

Publicly launch the inquiry |

November 2017 |

|

Subsequent requests to the TPS for data and documents |

July 2017 – September 2018 |

|

Receive and input SIU case information into data collection template |

September 2017 – July 2018 |

|

Preliminary analysis of SIU data by Dr. Wortley |

July – November 2018 |

|

Receive data and documents from the TPS |

November 2017 – October 2018 |

|

Meeting with the TPSB regarding TPS production of data and documents |

January 2018 |

|

Three meetings with TPS technical staff and TPS Counsel to better understand their data systems and how to link use of force with race and other case-related information |

February and March 2018 |

|

Receive documents from the TPSB |

September 2017 and April 23, 2018 |

|

Outreach to Black communities |

Ongoing |

|

Provide briefings on Interim Report findings to Black community leaders, the SIU, TPS and TPSB, and the Government of Ontario |

October – November 2018 |

|

Launch Interim Report on the inquiry |

December 10, 2018 |

a) Outreach to Black communities in Toronto

As part of the inquiry process, the OHRC committed to “receive information from affected individuals, interested groups and organizations.”[60] Recognizing the diversity within Black communities, the OHRC put out a public call for organizations and individuals to discuss their experiences of anti-Black racism involving the TPS. A dedicated phone line and email was set up to receive submissions. On the advice of Black community leaders, the OHRC worked with a number of organizations serving Black communities and/or challenging anti-Black racism to hold focus groups and gather experiences of Black persons with the TPS that fall within the scope of the inquiry.

The OHRC met with approximately 130 individuals from Black communities, including in Malvern, Central Etobicoke, Jane and Finch, and York South-Weston. The majority spoke to the OHRC as part of focus groups that were co-organized with these organizations, which identified and reached out to the participants. The OHRC also arranged further meetings with individuals who wanted to share their stories outside of focus groups. The OHRC’s outreach is ongoing, and it will continue to hold focus groups and interviews and meet with representatives from Black communities, and community and advocacy groups across Toronto.

b) Documents and data requested from the TPS, TPSB and SIU

The OHRC requested a broad range of data and documents from the TPS, TPSB and SIU pertaining to the period between January 1, 2010 and June 30, 2017 (see Appendix C – Inquiry letters). Overall, the OHRC has received data and documents from the TPS, TPSB and SIU that are responsive to our requests. That said, the OHRC expects to seek additional data or documents or question representatives from the TPS, TPSB and/or SIU on matters that are or may be relevant to the inquiry.

TPS

The TPS provided some procedures and reports in the early months of the inquiry but took several more months to produce data and other documents. The OHRC began to receive data and documents on an accelerated basis after publicly launching the inquiry and calling upon the TPS to fully cooperate with our inquiry. Data and documents responsive to the OHRC’s requests were supplied in phases and on an ongoing basis (see Appendix D – Status of OHRC requests).

To date, the TPS has not:

- Produced unique civilian or incident identifiers unless they already existed in the carding/street check or charge, arrest and release data

- Linked use of force reports with general occurrence reports

- Produced free text fields from carding/street check data.

The OHRC also met with TPS technical staff and TPS counsel on three occasions in February and March of 2018 to better understand their data systems and how to link use of force with race and other case-related information.

TPSB

The TPSB produced policies, reports, minutes and other documents that are responsive to the OHRC’s requests (see Appendix D – Status of OHRC requests).

SIU

The OHRC received and analyzed about four and half years of SIU data regarding the TPS.

The OHRC requested information from SIU cases that were opened and closed between January 1, 2010 and June 30, 2017 as well as investigations that were ongoing for at least six months as at June 30, 2017. Important information for the analysis prior to January 1, 2013 was not available electronically, so the OHRC restricted its analysis to January 1, 2013 to June 30, 2017. The SIU provided the requested information, except case information from ongoing investigations or cases where the subject officers were before the criminal courts (see Appendix D – Status of OHRC requests). Five cases were before the courts at the time of data collection.

IV. Findings

a) Review of SIU case information involving the TPS

1. Methodology

The OHRC retained Dr. Scot Wortley, an Associate Professor at the University of Toronto’s Centre for Criminology and Sociological Studies, to analyze the SIU data. Dr. Wortley’s expertise includes racial profiling and social science methodology. He has been qualified as an expert by the Ontario Superior Court of Justice,[61] Canadian Human Rights Tribunal[62] and Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario.[63]

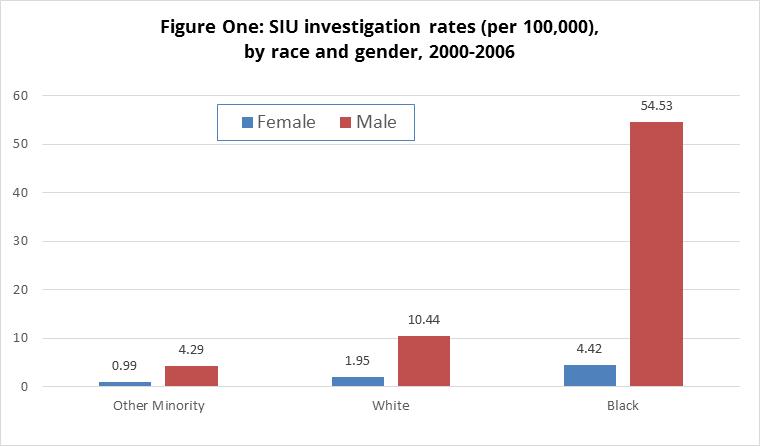

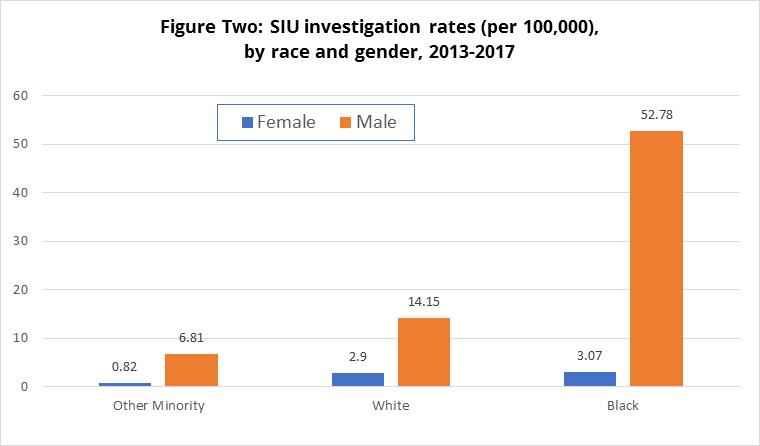

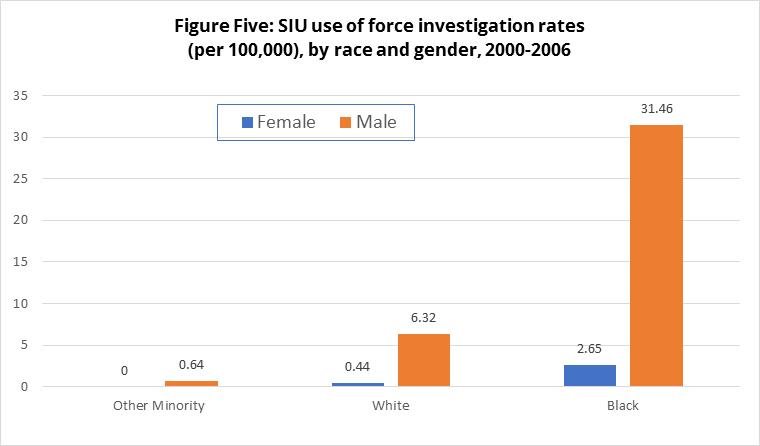

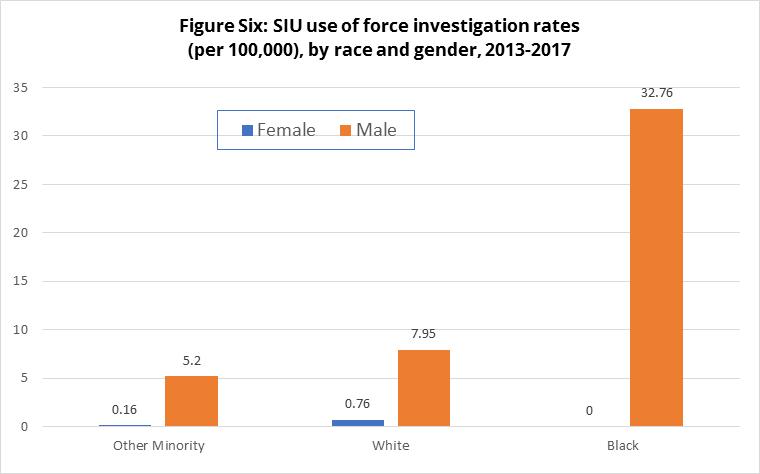

Dr. Wortley analyzed data from two periods: January 1, 2000 to June 6, 2006 and January 1, 2013 to June 30, 2017. The 2000-2006 data was previously collected and coded by Dr. Wortley in 2006 as part of the Ipperwash inquiry.[64] The 2013-2017 data was collected and coded by the OHRC as part of this inquiry.

From 2000-2006 and 2013-2017, much of the information gathered was from SIU Director’s Reports, which provide detailed information on each SIU investigation, including the time, date and location of the incident, characteristics of the civilian or civilians involved, the cause of injury or death, a description of the circumstances surrounding the incident, and the justification behind the Director’s decision to charge subject officers with a criminal offence or clear them of criminal wrongdoing. From 2000-2006 and 2013-2017, the SIU did not provide case information from ongoing investigations or cases where the subject officers were before the criminal courts.

The SIU did not collect race-based data between 2000 and 2006 or between 2013 and 2017. Between 2000 and 2006, race was determined by relying on case photographs, interviews with SIU investigators, SIU investigator notes and/or photographs of the civilian that appeared in the media.

Between 2013 and 2017, race was determined by relying on SIU investigator notes, case photographs, media coverage, social media and/or TPS documents (i.e. officer notes, General Occurrence Reports, TPS charge documents, incident summaries). In the majority of cases (77.4%), race was determined by examining SIU investigator notes and TPS documents. In other words, the OHRC relied extensively on how investigators and officers recorded race (i.e. their perceptions of race). Perceptions of race are at the heart of racial profiling.[65] In a minority of cases, the OHRC had to determine race itself by examining SIU photos (16.5%), media coverage (2.5%) and social media (0.8%). The OHRC acknowledges that there could be a small margin of error. However, as indicated in the Wortley Report, the OHRC employed a “conservative coding strategy” when determining race.

The SIU conducted 246 investigations involving the TPS between 2000 and 2006. However, 59 of these cases were “closed by memo” soon after the files were opened. Investigations are “closed by memo” when, early in investigations, the SIU determines that the civilian injury was not serious enough to meet the threshold for the SIU’s jurisdiction or was not directly caused by police activity. Therefore, the final sample analyzed was 187 completed investigations.

The SIU conducted 319 investigations involving the TPS between 2013 and 2017. However, 75 of these cases were “closed by memo” and not analyzed, leaving 244 completed investigations. The OHRC was not provided with SIU case information for five cases involving subject officers that were before the criminal courts.

Dr. Wortley used population estimates from the 2006 and 2016 censuses to identify the representation of racial groups in SIU investigations from 2000-2006 and 2013-2017 respectively.

For a more detailed explanation of the methodology, see Dr. Wortley’s Preliminary Report Race and Police Use of Force: An Examination of Special Investigations Unit Cases involving the Toronto Police Service (Wortley Report) in Appendix E.

2. Wortley Report findings

The Wortley Report confirms that Black people are much more likely to have force used against them by the TPS that results in serious injury or death. Black people are “grossly over-represented” in SIU cases that involve police use of force[66] and “little [has] changed” since the early 2000s.

The data is disturbing and raises serious concerns about racial discrimination in use of force.

Dr. Wortley notes that over-representation of Black civilians appeared to increase with seriousness of police conduct. In 2016, Black people made up 8.8% of the Toronto population. However, from 2013-2017, they made up:

- 25.4% (62)[67] of SIU investigations

- 28.8% (36) of police use of force cases

- 36% (9) of police shootings

- 61.5% (8) of police use of force cases that resulted in civilian death

- 70% (7) of police shootings that resulted in civilian death.

These numbers demonstrate that Black people are disproportionately represented in incidents involving TPS use of force that resulted in serious injury or death.

Dr. Wortley also analyzed SIU case-rates, which allow for a direct comparison of the experience of White people and Black people even though the population of White people in Toronto is greater than the population of Black people.[68] Between 2013 and 2017, a Black person was far more likely than a White person to be involved in an incident involving Toronto Police use of force that resulted in serious injury or death. A Black person was:

- 3.1 times more likely than a White person to be involved in a SIU investigation

- 3.6 times more likely than a White person to be involved in a police use of force case

- 4.9 times more likely than a White person to be involved in a police shooting that resulted in serious civilian injury or death

- 11.3 times more likely than a White person to be involved in a police use of force case that resulted in civilian death

- 19.5 times more likely than a White person to be involved in a police shooting that resulted in civilian death.

Regardless of race, most civilians from 2013 to 2017 who were involved in police use of force cases were unarmed (67%) at the time of their encounter with the TPS. Overall, a higher proportion of White people had a weapon in police use of force cases. While a higher proportion of Black people had a gun (8.3% of Black people vs. 3.6% of White people) or a knife (16.7% of Black people vs. 14.7% of White people) in police use of force cases, a higher proportion of White people had a gun (20% of White people vs. 11.1% of Black people) in police shootings.

Although there were more allegations of Black people (41.7%) resisting arrest than White people (25.5%), White people were more likely to have a criminal record (54.5%) and to have allegedly threatened or attacked police (61.8%) than Black people (44.4% – criminal record; 44.4% – threatened or attacked police).

From 2013-2017, according to SIU reports, most civilians (70.4%) were not exhibiting mental health issues at the time of their encounter with the TPS that involved use of force. However, a large proportion of use of force cases involved people exhibiting mental health issues (29.6%).

Dr. Wortley’s analysis suggests that White people are “most often exposed to police use of force when experiencing a mental health crisis.” White people are over-represented in use of force cases where the civilian was exhibiting mental health issues.[69] Like White people, Black people are over-represented in use of force cases where the civilian was exhibiting mental health issues.[70] However, unlike White people, Black people are over-represented in use of force cases in which no mental health issue was noted.[71]

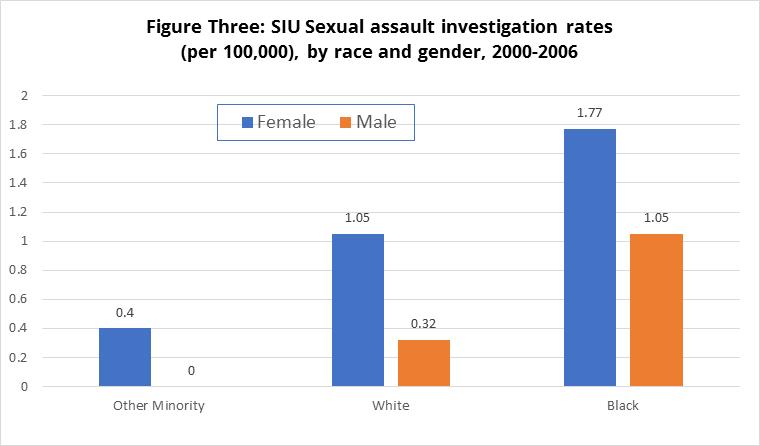

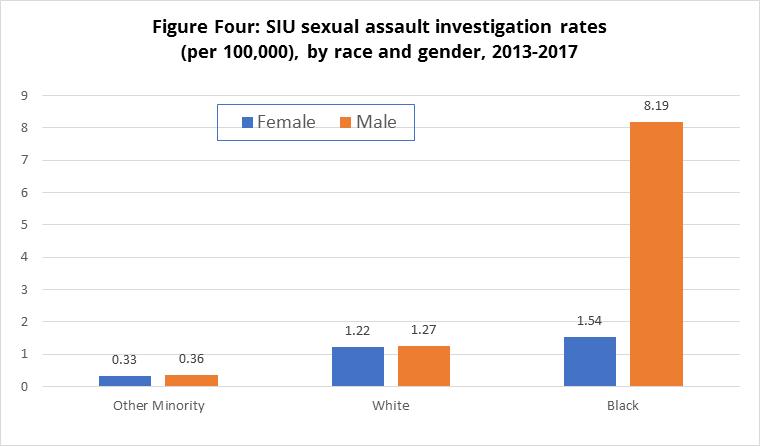

Black males were also significantly over-represented in sexual assault investigations. From 2013 to 2017, Black males were 6.1 times more likely to appear as a complainant in a SIU sexual assault investigation than their presence in the population would predict. They were:

- 5.3 times more likely than Black females to appear as a complainant in a SIU sexual assault investigation

- 6.4 times more likely than White males to appear as a complainant in a SIU sexual assault investigation.

Male complainants alleged that they were sexually assaulted during police frisks or strip searches. This is consistent with comments by the Supreme Court of Canada that “[w]omen and minorities in particular may have a real fear of strip searches and may experience such a search as equivalent to a sexual assault.”[72]

From 2013 to 2017, Black females also were 1.3 times more likely than White females to appear as a complainant in a SIU sexual assault investigation.

TPS officers were cleared of criminal wrongdoing in over 90% of all SIU investigations across both periods, and investigation outcomes did not vary significantly by race. Finally, in a “significant minority” of SIU cases, the SIU Director noted problems with police cooperation. These problems were no more likely when investigating a case involving a Black civilian.

3. SIU Director’s Reports

The OHRC also reviewed SIU Director’s Reports for investigations involving Black people from January 1, 2013 to June 30, 2017. These Reports contain an incident narrative and the SIU’s analysis which provide insight into the experiences of members of Black communities during encounters with TPS officers that resulted in serious injury, death or alleged sexual assault. These Reports also describe the experience of the SIU in investigating some of these encounters, and highlight some of the challenges that SIU investigators may face.

The OHRC observed several themes related to the TPS and Black civilians, including the fact that the SIU stated in a number of cases that there was:

- A lack of legal basis for police stopping and/or detaining the civilian at the beginning of the encounter

- Police conducting inappropriate or unjustified searches of the civilian during the encounter

- Police laying charges against the civilian that are without merit

- A lack of cooperation by police during the investigation by the SIU.

The OHRC has not compared the experiences of Black persons described in the SIU Director’s Reports with those of other groups to see whether SIU investigations involving Black persons are more likely to reveal such concerns.

a. Lack of legal basis for stops and/or detentions

The SIU Director determined that there appeared to be no legal basis for the police to stop and/or detain Black civilians in several cases.[73] For example:

- In August, 2013, two TAVIS (Toronto Anti-Violence Intervention Strategy)[74] officers spotted a Black man and his friend in a park and decided to stop them for an investigation. The officers stated that they stopped the man because he was in a park in which drugs were a problem, and passed a knapsack to his friend. In his report, the SIU Director found that the officer likely did not have reasonable suspicion that the man was engaged in criminal activity and that the detention of the complainant appeared to be unlawful.

- In March 2015, three TPS officers on bike patrol stopped a Black man for an investigation. The officers stated they were investigating him for drug activity because they believed they had seen the man toss away something that could be drugs, and because he was walking “with a purpose” and trying to avoid looking at the officers. The SIU Director commented in his report: “There is much that is disconcerting about this case. It is quite arguable, for starters, that the officers did not have lawful grounds justifying [the Complainant’s] initial detention. The problem is that [the subject officer] appears to have proceeded on the basis of a hunch fed by nothing more than having observed [the Complainant] appear to “discard” an object as he made his way on foot… something less, in my view, than the type of objectively discernible circumstances capable of giving rise to a reasonable suspicion.”

- In February 2013, a Black man was detained and arrested in a night club during a drug investigation. The police stated that the civilian was detained because he matched the description of a suspect that the police were searching for as part of a criminal investigation. However, the SIU Director questioned this reason after finding that the civilian did not actually resemble the description of the suspect from the witness officers’ notes. The Director’s Report noted: “[The detective’s] justification for physically detaining [the complainant] was that [the complainant] was black and wearing plaid, which [the detective] recalled were included in the description he was provided for one of the targets. Given that [the detective] lost his notes containing this description, it is not possible to confirm the precise description he was referring to at the time. The description other witness officers received for the same target was that he was brown, accompanied by a variety of other features that clearly did not match [the complainant].”

b. Inappropriate and unjustified searches

In several cases, the SIU Director questioned the legality of TPS officer searches of Black civilians.[75] For example:

- In March 2015, police stopped and searched a Black man for drugs, despite his protest to the detention and search. In his report, the Director questioned the legal basis for stopping him, and commented on the subsequent search: “I am also not persuaded that the pat down search that ensued was lawful.”

- In January 2013, a Black man was riding his bicycle when he was stopped by TAVIS officers. Two officers held each of his arms while a third officer asked him whether he had anything on his person. He responded in the negative. The subject officer then grabbed and pulled his shorts and underpants down to his ankles, leaving his genitals exposed to the public for approximately one minute. During this time, the three officers stood laughing at him. The SIU Director found that the strip search was unnecessary, and that it was carried out in an improper way (i.e. in public view).[76] In his report, the SIU Director stated: “There would appear to be no justification for this strip search.” He further stated: “The stripping of [the complainant’s] shorts and underpants in public view was a complete violation of his rights.” Additionally, at the man’s trial, the trial judge found the strip search was an “egregious violation” of the complainant’s Charter rights against unreasonable search and seizure and arbitrary detention.

c. Arrests/charges without merit

Some SIU investigations involving members of Black communities describe police arresting or charging the civilian, without a proper legal basis.[77] For example:

- In May 2015, a Black male was arrested based on information that he had a firearm. Ultimately, no firearm was found. In his letter to the chief of police, the SIU Director noted that “the Complainant was charged with assault with intent to resist arrest even though nothing before the charging officer supported it.” He further stated that “Baseless charges – even if quickly withdrawn by the Crown – prejudice the accused and undermine the integrity of the justice system.”

- In February 2015, a Black male was arrested by two officers outside a night club after refusing to leave the area. In his report, the SIU Director noted that the officer who chose to provide a statement to the SIU[78] had difficulty identifying the predicate offence justifying the arrest. The Director took issue with the officer’s assertions of grounds under the Trespass to Property Act because the complainant was on public property at the time of the arrest. The Director also questioned the officer’s assertions of grounds to arrest the complainant for public intoxication under the Liquor Licence Act, stating that “an arrest for that offense is not made out in the absence of significant intoxication and a real safety threat posed by the arrestee, neither of which appears to have been in evidence at the time.”

d. Lack of cooperation with the SIU investigation

In many SIU investigations the SIU Director described difficulties in conducting the investigation due to a lack of cooperation by TPS officers. However, as noted in the Wortley Report, it appears that these problems were no more likely when investigating a case involving a Black civilian. Nonetheless, individual cases may still involve possible racial discrimination.

Some of the issues identified related to improper SIU notification by the police. The Police Services Act and regulations require police to immediately notify the SIU of incidents where there is a serious injury or death involving police.[79] However, the SIU Director noted in several investigations involving Black civilians that the police did not notify the SIU, that the notification was delayed, or that there was another problem with the notification, such as misleading content. For example:

- In an investigation into the custody injury of a Black male in February 2013, the SIU Director noted in his report that a witness officer’s notes contained evidence that on the same day the complainant was injured the police were aware that the complainant may have suffered a serious injury. However, the police did not notify the SIU. The SIU was not notified of the injury until four days later and was notified by the complainant himself, not by the police.

- In an investigation into an injury sustained by a Black man during an arrest in September 2015, the SIU Director stated: “it should be noted that [the complainant’s] injuries appear to have been diagnosed well in advance of the TPS notifying the SIU.” The SIU was not notified until more than nine hours after the complainant was transferred to a trauma centre hospital and diagnosed with a fractured spine.

- In an investigation into the injury of a Black male during an arrest in May 2015, the SIU Director noted in his letter to the Chief of Police: “The notification to the SIU was misleading in its description of the Complainant’s arrest and cast the Complainant in a disfavorable light, again without foundation.” The Director stated that this action “threatened to impede the SIU investigation and raise questions about the reliability of TPS information.”

- The SIU investigated the high profile case of Dafonte Miller, a 19-year-old Black male who alleges that he was beaten with a metal pipe by an off-duty TPS officer for no justifiable reason on December 28, 2016. The SIU investigated and laid charges against the TPS officer and his brother for aggravated assault, assault with a weapon and public mischief. The OHRC does not have access to the SIU investigation because the matter is currently before the courts. However, Mr. Miller’s complaint to the OIPRD alleges that, although the TPS was made aware of his serious injuries, including a broken nose, broken orbital bone, bruised ribs, a fractured wrist, loss of all vision in his left eye and reduced vision in his right eye, the TPS failed to notify the SIU. The SIU was notified by Mr. Miller and his counsel on April 27, 2017, almost four months after Mr. Miller was injured. Mr. Miller makes several other allegations regarding TPS conduct, including: discrimination, a lack of legal basis for the officer to stop and question him, an unjustified search, unnecessary and excessive force used against him, and additional problems with the TPS investigation into this incident (for example, that the investigation was conducted, in part, by the officer’s father).[80]

Problems with police cooperation were also noted while investigations were underway. The SIU Director raised a variety of issues including witness officers refusing to answer questions, officers not completing notes or destroying them, and police attempting to access security camera footage while a SIU investigation was in progress, all of which contravene regulations under the Police Services Act.[81] For example:

- In his report on the investigation into the injury of a Black male during an arrest in February 2013, the SIU Director stated: “In sum, this investigation was a highly unsatisfactory one.” He asked the Chief of Police to discipline a witness officer for refusing to answer a question from the SIU, a breach of a regulation. The SIU Director also stated that another witness officer destroyed his original notes, a breach of a TPS policy on memo books. The SIU Director further noted that many of the witness officers interviewed had not completed their notes until the day after the incident, an apparent breach of regulations.

- In the investigation into the police shooting death of Andrew Loku, a Black male, in July 2015, the SIU Director noted difficulties with the investigation including the police accessing video surveillance footage before the SIU arrived on scene. At the time of writing his report, the SIU Director commented that he had not yet heard an adequate explanation for why [the police officer] saw fit to attempt to review and download the video recordings captured by the cameras situated where the shooting occurred. In his report, the SIU Director stated: “I note for the record that this case is another example in which the post-incident conduct of some officers threatened to publicly compromise the credibility of the SIU’s investigation.”

b) OHRC engagement with Black communities and review of decisions

As indicated above, the OHRC met with approximately 130 individuals in Black communities. The majority spoke to the OHRC as part of focus groups that were co-organized by other organizations. These organizations identified and reached out to the participants. A few individuals chose to provide further details about their experiences in private conversations with the OHRC.

The goal of the focus groups was to hear about interactions between members of Black communities and the TPS that fall within the scope of the inquiry. The focus groups covered topics of trust, stop and question practices/carding, aggression/use of force, the impact of race in certain charges and conditions for release, and recommendations to address racial profiling.

The OHRC acknowledges that the responses may not reflect positive interactions that may have taken place with the TPS. However, many participants overwhelmingly felt a sense of mistrust with the TPS. Also, some recounted specific interactions with the TPS and/or experiences of their family and friends that contributed to feelings of fear/trauma, humiliation, lack of trust and expectations of negative police treatment.

Outreach to Black communities has allowed the OHRC to better understand the lived experiences of Black communities and their concerns regarding racial profiling and racial discrimination by the TPS.

We also reviewed decisions of the Courts and the HRTO made between 2010 and 2017 where there were findings of racial discrimination and/or racial profiling, along with decisions of the OIPRD. Examining these cases has been important to understand when and how racial discrimination may occur against Black people by the TPS.

Through our review of case law and community engagement, we have been able to better understand the lived experiences that lay at the heart of Black communities’ concerns about racial profiling and discrimination by the Toronto Police. Themes that have emerged from these engagements include:

- Unnecessary stops, questions and searches by the TPS

- The use of excessive force by the TPS

- The laying of unnecessary charges.

1. Unnecessary stops, questioning and searches

Court and tribunal findings

Courts and tribunals have heard evidence and made findings of racial profiling and racial discrimination of Black persons by the Toronto Police in stops, questioning and searches. That is, race was a factor in Black people being stopped, questioned and/or searched.

For example, in a civil suit against the TPSB, the Divisional Court determined that a Black man was stopped and searched, among other things, because of his race. He was spotted by two police officers while walking home from prayers in January 2011, and stopped because one of the arresting officers suspected that he was violating bail terms by walking alone, and for potentially having a weapon because his hands were in his pockets.[82] His hands were in his pockets because he did not have gloves and it was cold outside. The officers stopped the man and asked him questions. They testified that he was hostile to police and refused to take his hands out of his pockets. One of the officers, among other things, emptied his pockets and handcuffed him, leaving his hands exposed to the cold for about 20 minutes. He was not charged with any offence.

The trial judge found that the detention was unlawful, the search of his pockets was a breach of his right under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms to be free from unreasonable search, and that his rights were violated when he was not told why he was detained or given his right to counsel upon being detained. The police officers were also found to have lied when the Court questioned them about their behaviour. The Plaintiff was awarded $5,000 in general damages for the battery, $4,000 for the Charter breaches and $18,000 in punitive damages. The trial judge did not find that there was racial profiling, which was appealed. The Divisional Court accepted the appeal and found that there was racial profiling. The Divisional Court increased the damage award to $50,000 for the Charter breaches and $25,000 in punitive damages and stated:[83]

The only reasonable inference to be drawn from the fact that both officers, without any reasonable basis, suspected the Appellant of criminal behaviour, is that their views of the Appellant were coloured by the fact that he was black and by their unconscious or conscious beliefs that black men have a propensity for criminal behaviour. This is the essence of racial profiling.

In this case, the officers' unreasonable beliefs about the Appellant caused them to assault the Appellant, unreasonably search him and forcibly restrain him. In other words, instead of presuming his innocence, they assumed and acted as if he were guilty and dangerous. He must be violating his bail and he must be carrying a gun. These assumptions, for which there is no explanation other than the colour of the Appellant's skin, caused them to blatantly and aggressively violate the Appellant's constitutional rights.

Similarly the Ontario Court of Justice found that a December 2015 traffic stop of a Black man was “aggressive” and “verbally abusive.”[84] The individual was stopped after midnight by two TPS officers for apparently not stopping at a red light before making a right turn from Eglinton Avenue onto Oakwood Avenue. The man then made a left turn into a laneway where he was pulled over. He was charged with refusing to provide a breath sample and breach of probation. The Court acquitted him and found that there were egregious violations of his Charter rights.[85]

With the assistance of dashcam video, the Court found that the police used the Highway Traffic Act stop as a “pretext” to conduct a further investigation. The detention, which began lawfully, became unlawful. One of the officers banged on the man’s car and yelled at him to open the door. The other officer ordered him to exit the car because it was a “high drug area” and threatened to drag him out through the passenger window. The officers failed to ask for his documents or accept the documents he offered. Remaining calm and respectful, he reminded the officers that they should give him a ticket if all that he did was fail to stop at a red light before making a right turn. At one point, the officers walked away from his car. When they returned to the car, one officer stated that she could smell alcohol, yet the window remained closed (the man indicated earlier that it was broken). He refused to provide a breath sample. No drugs or weapons were found in his car.[86]

The Court found it troubling that the officers justified their actions based on the location of the stop:[87]

Every individual is entitled to equal treatment under the law and not be subjected to uneven or heavy handed police tactics based on a stereotypical presumption that all individuals in a certain area must be involved in, or have a connection to criminal activity in the area. It does not matter if the person being investigated is in a neighborhood considered to be affluent and crime-free or an area considered to be high crime.

Lived experience of Black communities in Toronto

In our discussions with members of Black communities, the OHRC heard frequent complaints of police officers conducting unnecessary stops, questioning and searches. Most of the people the OHRC spoke to felt that it was because of the colour of their skin.

The OHRC heard about instances where socio-economic status and race may intersect. For example, while driving, Black individuals reported being pulled over more often and questioned by the TPS if they drove a nice car, were in a predominantly White area or had other males in the car.[88]

In other instances, Black individuals reported they were stopped while walking, because they “matched the description” of another suspect.[89]

One Black youth described a 2017 incident where he was running to school, excited for a special event. As he neared the school, he heard sirens when a TPS vehicle pulled up beside him. An officer approached the Black youth and asked him to have a seat on the curb with his hands behind his back. The youth asked the officer why he was stopped and was told that there had been an incident nearby and that he matched the description of the suspect and because he was seen running with his sweater hood up over his head. The officer asked the youth for his information and released him shortly after. The incident took place in full view of the Black youth’s school yard where students were assembled.

I was feeling embarrassed. This is not who I am. This is not who I want to be. After that, people were looking at me different like I was a criminal or some type of thug.[90]

Another individual said he had just come back from watching Macbeth as part of a school trip. While waiting at the bus stop on his way home, a TPS officer drove past him and then made a U-turn to come and speak to him.

…long story short he said there was a robbery across the street and I fit the description...I find it’s always the same thing… I always match the description. They never tell you what the description is. The description is you.[91]

One individual described crossing the street with 15 other individuals approximately two years ago, and being the only one flagged down by the TPS.

I went over and [the officer] said, “Can I have your papers please?” It was the first time since I moved here that someone asked me for my identification papers, except while driving…

He left me there on the sidewalk and went into his car to enter the data… Obviously, he didn’t find anything, because I don’t sell drugs… He came back with a[n] $85 ticket, and that was the first time I heard the word jaywalking… there were other pedestrians doing the same thing but he did not stop any of them.

I was the only one who was stopped, which is why I said, you stopped me because I am Black. [92]

Another individual described an incident four years ago when he was approximately 14 years old. He was running around the neighborhood as part of a game he was playing with his friends when TPS officers stopped and arrested him. According to the individual, the officers thought he had a gun or had stolen something and was trying to run away. They stopped him, arrested him for allegedly having a gun and stealing and eventually let him go. “… They asked for my name and asked me why I was wearing all black.” He was released after he explained he was playing a game with his friends.[93]

In early 2018, on his way home after work, a Black man told us he was stopped and questioned by two TPS officers on the street just outside his workplace. They asked him if he had any “weed” on him. He said no, but then was asked for his identification and to consent to a search. A search of his hoodie, pants and shoes all took place on the sidewalk in full view of onlookers and his work colleagues. He was then let go. On his way home he reported thinking:

… I hope I don’t get stopped again on my way home now. [94]

The OHRC heard about an incident in 2011 where the TPS followed a car with a Black driver and passenger before stopping it. The passenger told us that both of them were detained, searched and questioned by the officers. When the passenger asked why he was being subject to police action, he recalled being told by the officer who detained him “If you don’t shut up, I’m going to punch your teeth in.” He was placed in the back of the police cruiser while the driver was questioned separately. The passenger remembered being asked for his name, birthdate and address, and the officer searching his information on the squad car computer before he and the driver were let go:[95]

I felt captured… they didn’t have the right to pull [us] over, search [or] question. No probable cause… didn’t break [the] Highway Traffic Act… There was nothing wrong with the car…

Finally, one Black youth told the OHRC that he was singled out and subjected to a random search by TPS officers. The officers told the youth they were investigating a report of a robbery in the area. The suspect was allegedly wearing a jacket that was similar to the one the youth was wearing that day. The youth recalled the officer’s hand on his gun throughout his search. The youth told us he was used to incidents like this, and that it was “normal” and just “going to happen.”[96]

2. Excessive force

Court, tribunal and police oversight body findings

There are confirmed court and tribunal findings of racial discrimination in TPS officer use of force.

In Elmardy, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice held that the plaintiff was punched in the face and forcibly restrained in 2011 because he was Black. The use of force followed the discriminatory stop described above.[97]

In September 2016, a Black man was arrested after he stabbed a man in the cheek in a downtown Toronto restaurant. Once he was arrested, handcuffed, and seated in the back seat of the cruiser, in-car video evidence showed a Toronto Police officer pepper spraying him. He also suffered lacerations to his face after being struck by the officer’s baton during the arrest.[98]

The Ontario Court of Justice concluded that the officer used excessive force; the video evidence showed clear “police brutality” and the facial strikes with the baton were not necessary to effect the arrest. The Court stayed the charges of assault police, possession of a knife, possession of cocaine, and uttering threats as a result of the excessive force and its significant harm.[99] The man was found guilty of assault with a weapon and threatening death because of the incident with the other man.[100]

In April 2018, the Toronto Star released a portion of the in-car camera footage that was presented at his trial. The video shows him crying out in pain, pleading for help, saying he cannot breathe, and asking the officers if he is going to die.[101]

In January 2017, officers were caught on video stomping on and tasering a Black man even though it appeared he was not resisting arrest. The incident reportedly began when police received a call about a man spitting at an employee at a homeless shelter in downtown Toronto. Witnesses said the man began punching the officer in the face. When backup arrived, he was placed in the back of a cruiser. According to a TPS spokesperson, he kicked out the window of the cruiser and bit an officer. The spokesperson claimed that the subsequent force used by officers was justified. The man was charged with nine offences.[102]

The video was recorded by a bystander who filed a complaint with the OIPRD. The OIPRD substantiated four allegations of misconduct in its report, including that a Sergeant used excessive force.[103] The OIPRD found:

- The individual was tasered six times while handcuffed. He did not move. For the majority of this time, he was “handcuffed to the rear, prone face down on the ground, and being physically controlled by four officers.” He was also shackled at some point.

- The Sergeant’s stomping on his leg and taser use were not justified as a response in the event that he moved his head in an attempt to bite an officer.

- The Sergeant engaged in discreditable conduct by improperly ordering another officer to interfere with the bystander’s lawful presence at, and recording of, the incident. The Sergeant yelled at the officer to “Get that guy out of my face.” The comment was made in reference to the bystander recording the incident.

- Two officers engaged in discreditable conduct through their statements to the bystander:

- One officer told the bystander: “You’re a witness we’ll have to seize your phone.” The bystander was 20 feet away and not interfering with police activity. The officer’s interactions with him were “solely for the purpose of intimidating” him to either move where he could no longer record or stop recording.

- The other officer’s suggestion to the bystander that the individual had AIDS and that he may be infected was “disgusting.” The officer also intimidated the bystander when he stated “Stop recording or I’ll seize your phone as evidence and then you’re going to lose your phone.”

In 2014, the Ontario Court of Justice found that a Black man committed the following offences: obstruction, impersonation and possession of marijuana.[104] He was arrested because he was intoxicated in a public place in January 2012. He was acquitted of assault police and threatening an officer. With the assistance of video, the Court found that he was the victim of excessive force during booking and in the holding cell of 43 Division in Scarborough. The Court stayed the remaining charges as a result of the serious misconduct committed by the officers.[105]

The Court found that a TPS officer assaulted the man during booking when the officer bent his palm towards his forearm and raised his arm up behind his back and squeezed. It was a deliberate attempt to stop him from complaining about his injured eye to the officer.[106]

The Court held that excessive force was used on the man in his cell by the four officers who took him there, and who colluded and lied in their evidence in an effort to justify their behavior. The officers inappropriately reacted to the man being verbally abusive. One officer grabbed his head twice and pushed it down towards his lap. Three of the officers then leaned into the corner on top of the individual. All four officers assaulted and further injured him in the cell while he was shackled, restrained by both arms, already injured, and defenseless. His injuries were significant. Medical records showed that he had concussive recurring headaches, abrasions and bruising to his head, swelling of his left eye, neck stiffness and cervical strain.[107]

Lived experience of Black communities in Toronto

Several individuals the OHRC spoke to believed they were the victim of excessive force by TPS officers.

One person described playing basketball late one night in 2010 or 2011, when he was approached by several TPS officers. The officers shone their flashlights on him and his friends and asked them to explain what they were doing out so late at night. The individual chose not to answer and instead continued to play basketball. He remembered a flashlight being shone in his eyes before he was punched in the jaw by an officer:

I didn’t see it coming at all because I was blinded.[108]

His attempt to fight back was met with a takedown by several officers who punched him, hit his head and brought him to the ground. He said that the officers kicked him, twisted his genitalia and hurt his leg. They handcuffed him and then asked for his information. After approximately 15-20 minutes, the officers let him go and told him to go home. After the incident, he tried to file a report at the police station but was told that his complaint would get thrown out:

I cried and had a whole outburst after that and punched everything. I was crying after they let me go and was walking toward the building and was crying. I never cried before that.

In another incident, a mother described a raid on her house in 2014 where her son was stomped on, his face injured and racial slurs were used by a TPS officer. He was handcuffed and taken to the hospital for medical treatment and was then released without charges. During the raid, another son was grabbed and handcuffed at gunpoint. The officers pulled his pants down, and asked “Where are the guns?” The mother recounted that, when her son responded that there were no guns, he was told that if they found a gun his entire family would go to jail. No weapons were found, no arrests were made, and no charges were laid. All of the sons identify as young Black men.

The family described being severely traumatized. The mother stated:

…It was scary and you got a guy standing there with a big gun stepping on his face and you can’t see how much pressure he’s putting but I can hear [him].

…[the worst part] was seeing [my son] assaulted and not being able to see him afterward – them bringing me down separately to [my other son] and not knowing what was going on upstairs and then [they bring him] down and almost passing out – he was passing out looking pale. Made me feel terrible, terrible, terrible. I was terrified as a mother. Then he was going in an ambulance. I’m thinking he’s in good hands but he was in the hands of the TPS… I could have gone with [him] but I was worried about what was going on in my house with the rest of the boys – that torn feeling like should I go or should I stay based on how out of control it was getting – it was terrifying.

Her son stated:

…I’m still dealing with the back pain that is all stemming from this incident – I still have back pain to this day and I was very athletic and active – since this I haven’t been the same person at all – even my attitude and standing up to the police, I used to do that but I find myself questioning whether I can say anything or am I going to get arrested… I’m still shaking because it’s a traumatic thing…[109]

3. Unnecessary charges

Courts and tribunal findings

In R v Thompson, the Court held that the “real reason for the stop was racial profiling.”[110] Justice Hogan concluded that the detentions of the vehicle and a Black man were arbitrary, there were no reasonable and probable grounds on which to base an arrest or search his pocket, he was not advised of the reason for the detention or that he was under arrest, and the force used against the man was unnecessary.[111] The charges for possession of marijuana and failure to comply with a recognizance were dismissed. He was also found not guilty of assaulting a police officer.

The man was a passenger in a car that was stopped by a TPS officer in September 2011. The police officer testified that the car had not signalled when switching lanes, and once he had come in line with the vehicle, he noted the rear passenger was not wearing a seat belt. When stopped, the man came out of the vehicle as the officer got out of his, prompting a physical confrontation. The officer attempted to get his hands out of his pockets and a physical struggle ensued. At some point during the struggle, he was able to free himself from his jacket and fled. The officer subsequently found marijuana in his jacket, and he was later arrested and charged with possession of marijuana and failure to comply with a recognizance along with assaulting a police officer.[112]