Jeffrey Lewis

Director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Program, The James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies

About the image

On April 27, the leaders of the two Koreas met in Panmunjom for the first inter-Korean summit in more than a decade. This summit is expected to be followed by the first-ever summit between the leader of North Korea and a U.S. President. The Trump Administration has announced that it is willing to accept an invitation from North Korea’s Kim Jong Un to discuss the “denuclearization” of the Korean peninsula between the leaders of the two countries. The possibility that Kim Jong Un will abandon his nuclear weapons, having “completed” the development of his nuclear deterrent seems like a long shot. But after a year of Trump taunts like “little Rocket man” and press stories about possible U.S. plans for a military strike to give Kim a “bloody nose,” most people are willing to give diplomacy a try — long shot or not.

Although the phrase being used is “denuclearization,” it is North Korea’s missile program that has brought us to this point. Indeed, when asked to define “denuclearization,” the White House said “it means that North Korea doesn’t have or isn’t testing nuclear missiles.”1 Since 2000, North Korea has developed three new generations of ballistic missiles to replace its Scud-based missile systems. In general, North Korea has sought to develop more sophisticated engines that use more powerful propellants.

The crisis atmosphere throughout 2017 was driven largely by North Korea’s successful testing of a new generation of long-range missiles that could deliver nuclear weapons against the United States. Any agreement on North Korea’s disarmament today will have to deal with North Korea’s arsenal of long-range missiles, a topic that was of secondary importance when the two countries negotiated the Agreed Framework that froze North Korea’s plutonium production infrastructure in 1994.

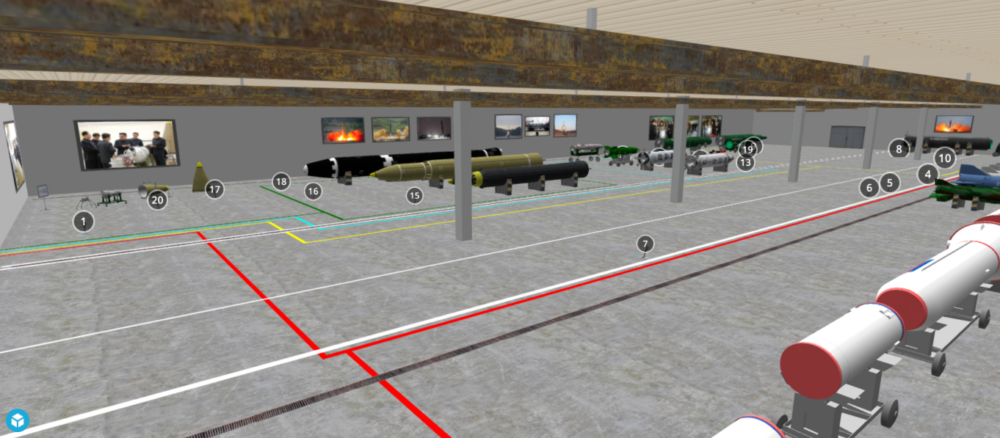

To help understand the scope of North Korea’s missile and nuclear programs, CNS has created a virtual museum of North Korean missiles that displays the evolution of its capabilities since the 1990s. This museum is an immersive 3D environment in which anyone can wander among models of the missiles and nuclear devices, and read about their development, using a computer, smartphone, or VR device (Google Cardboard, Oculus Rift, etc).

To view the model on your computer or any other device (including VR headsets such as the HTC Vive or Oculus Rift), open the model embedded below. View the VR model in Google Cardboard. Find instructions on how to use Google Cardboard.

The Agreed Framework began to falter in the mid-1990s for many reasons, and chief among them was North Korea’s development of long-range missiles. The Clinton Administration attempted to prop up the Agreed Framework by negotiating a missile agreement with North Korea. The two parties came close to an agreement in 2000 — Madeleine Albright even traveled to Pyongyang — but the Clinton Administration ran out of time.

In 2000, North Korea had a small number of missiles, all of which were based on a pair of Soviet Scud-B missiles. These two missiles had been supplied by the Soviet Union to Egypt in 1973. Egypt then retransferred them to North Korea, hoping that North Korea could reverse engineer them and boost Egypt’s own missile program. North Korea did this, developing its own Scud-B, an extended range version of the missile called the Scud-C, and a scaled-up version of the missile that the United States called the Nodong. North Korea also worked on a pair of space launchers that the United States called the Taepodong and Taepodong-2. The U.S. was worried Taepodong might be eventually deployed as an ICBM. These capabilities were rudimentary, not least because their basic Scud engine used a crude propellant combination of kerosene and nitric acid.

In 2000, it looked like it might be possible to freeze North Korea’s missile program in place, with a rudimentary arsenal of Scuds and a handful of Nodongs, in exchange for economic assistance and a limited number of space launchers.

Although the United States and North Korea were getting close to a deal, there were significant differences, as time ran short for the Clinton Administration. The main issue was which missiles would North Korea agree to abandon? The United States wanted the agreement to cover all missiles that could deliver a 500 kg payload to 300 km. The North Koreans, in contrast, intended to keep their Scuds, as well as a limited number of Nodong missiles, while promising not to build additional systems.

Then, as now, the North Koreans were seeking a summit agreement, and urged President Clinton to travel to Pyongyang for the final concessions. We do not know what final concessions, if any, the late Kim Jong Il would have offered President Clinton in person. In the end, with the domestic turmoil of the disputed 2000 election and other diplomatic efforts underway in the Middle East and Northern Ireland, Clinton chose not to get on the plane. The problem of North Korea would fall to the incoming Bush Administration. The missile talks never resumed and, soon, the Agreed Framework was “shattered” by John Bolton. North Korea was on the path that led to the development of a nuclear-armed ICBM.2

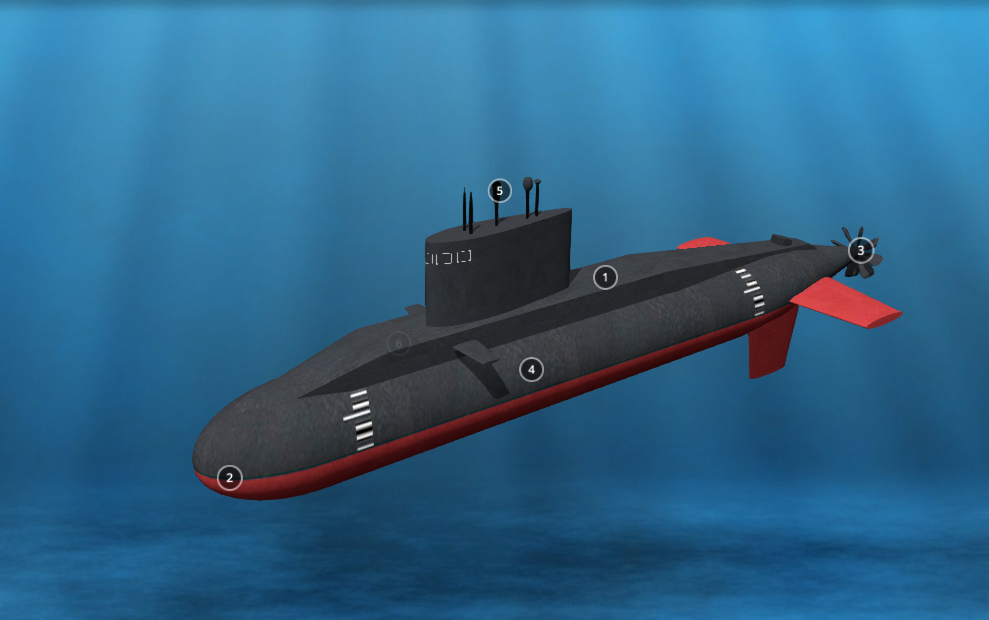

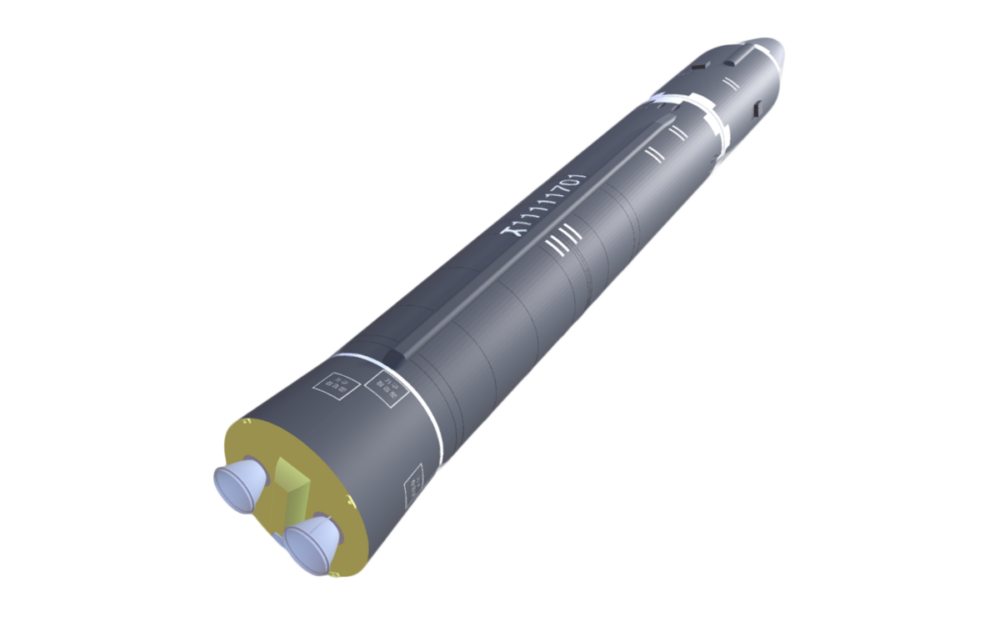

North Korea’s first effort to move beyond the Scud infrastructure on the way to an ICBM was a series of missiles based on a Soviet submarine-launched ballistic missile, called the SS-N-6. The SS-N-6 had a complex engine called the 4D10 that used modern, storable propellants (UDMH and NTO). North Korea built its own version of the SS-N-6 called the Musudan, as well as a pair of ICBMs that used a cluster of two 4D10 engines the KN-08 and the KN-14. Despite North Korea’s use of better propellants, these missiles appear to have largely been failures. The Musudan flew successfully only once in eight tries, while the KN-08 and KN-14 have never been tested.

North Korea’s second effort toward an ICBM proved more successful. In 2017, North Korea debuted an entirely new engine, which it called the “March 18 Revolution” engine. The March 18 Revolution uses the same liquid propellants as previous missiles but is based on a more sophisticated Soviet engine, the RD-250, that also uses UDMH and NTO. Over the course of 2017, North Korea tested a new intermediate-range ballistic missile (Hwasong-12) and a pair of ICBMs (Hwasong-14 and Hwasong-15) based on the March 18 engine. The Hwasong-15 is a large missile capable of carrying a nuclear weapon to targets throughout the United States. We estimate that its two-chambered engine may have a thrust of up to 90 tonnes.

North Korea is now developing a third generation of long-range ballistic missiles using solid fuel. North Korea has shown off a number of short- and medium-range systems including the Pukguksong-1 and its land-based cousin the Pukguksong-2. North Korea has hinted that there will be additional missiles in the Pukguksong-series, with ever greater range. Solid-fueled missiles offer a number of operational advantages over liquid-fueled ones and would represent yet another increase in North Korea’s missile capabilities. How quickly North Korea might develop a solid-fueled ICBM is anyone’s guess.

For now, however, North Korea and the United States appear poised to give diplomacy a try. North Korea has agreed to stop testing of intermediate- and intercontinental-range ballistic missiles, at least while talks with the United States continue.

As it was in 2000, the major issue today will be which missiles must be eliminated as part of any agreement, and which ones North Korea will keep. Unlike in 2000, however, the dispute is no longer over a handful of Nodong missiles. Today North Korea has a large and diverse arsenal of missiles systems, plus nuclear weapons.

This can all be a little overwhelming, which is why CNS created this virtual museum of North Korean missile and nuclear capabilities. Of course, that’s where these weapons of terror belong — in a museum. We hope that someday North Korea and other world powers can agree to remove nuclear-armed missiles from deployment, leaving the threat of nuclear holocaust to historians. Until then, you can use your computer or any VR device to visit a happier future.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

Using tools like commercial satellite imagery, radar, sensors, and media analysis, we can understand fleet details, construction, and potentially patrol patterns and behaviors.

More is known about Saudi Arabia's Strategic Missile Force capabilities due to the country's recent openness and open-source information. (CNS)

A collection of missile tests including the date, time, missile name, launch agency, facility name, and test outcome.