Watching the Devin Nunes memo blow up like a trick cigar a few weeks ago, Andrew Janz called himself "probably the happiest man in the country."

An assistant district attorney vying to oust Nunes from his California congressional seat, Janz said last week that his campaign war chest had more than tripled since Nunes announced he was releasing highly edited Top Secret information to discredit the FBI and Justice Department investigations into "Russiagate." That's not saying much: The Democrat's $240,000 purse would hardly cover the cost of robocalls in today's congressional elections, where winning candidates spend an average of $1.3 million—and Nunes already has three times that figure. And while there were some signs the incumbent's grip was slipping—a January poll commissioned by Janz showed Nunes leading a reelection bid by only five percent against a generic Democratic opponent—his highly edited release of the documents was proving popular among Republicans.

Still, Janz told me, "I'm feeling great, man. You've seen the memo. I think there's going to be plenty for folks on the Democratic side, and even some folks on the Senate Republican side, to poke holes in."

Which is what they did. "The Nunes Memo fizzled and failed," said former Nixon White House counsel-turned Watergate witness John Dean in a representative view. "The only thing it established is that Nunes is a nut job, and he has released anew the putrid stench of neo-McCarthyism."

"Nut job" has clung to Nunes's reputation as long as he's been chairman of the House Intelligence Committee (HPSCI, in Washington-speak). Or at least among Democrats (and some Republicans) who have decried Nunes's transformation of a once bipartisan national security panel into a GOP platform to attack Democrats.

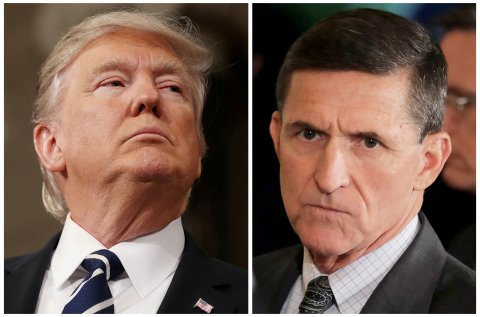

Janz thinks he knows why: Nunes's mentorship by Michael Flynn, the now disgraced former Trump national security adviser. "I know that they had a pretty close relationship," he said. Nunes served on the executive committee of the Trump transition team with Flynn, he noted, which was headed by Vice President Mike Pence, "and it seems to me like he never left. He's still on that team."

A descendent of Portuguese Azorean immigrants, Nunes grew up on a Central Valley, California farm and concentrated on water issues when he came to Congress in 2003. But his fundraising prowess for fellow Republicans endeared him to Representative Paul Ryan and House Speaker John Boehner, who in 2013 anointed him chairman of the intelligence panel.

Like many hawks back then, Nunes was in awe of Flynn, who had won praise for revolutionizing the hunt for terrorists in Iraq and Afghanistan. "This guy was one of the best intelligence officers in several generations," Nunes told me in a December 23, 2016 interview. "I don't know if you've ever met him, but Flynn is extremely smart. He really is top notch."

Nunes was speaking fives months after Flynn had startled many former military officers by leading "Lock her up" chants against Hillary Clinton at the Republican National Convention. It was also two years after the Obama White House has forced Flynn's resignation as director of the Defense Intelligence Agency. "What happened," Nunes told me, "is...he went out and said a lot of things that Obama didn't like…"

But that's not close to the full story on Flynn, whose battlefield talents didn't transfer well to running the DIA from 2012 to 2014. Not only were his executive skills lacking, according to many observers, including former Army general and Secretary of State Colin Powell, he quickly developed a reputation for indulging in conspiracy theories—or "Flynn facts," his aides derisively called them.

But Nunes embraced them. During Flynn's tenure, the neophyte intelligence overseer and the general came to share a number of beliefs. One was that the CIA was suppressing the release of documents captured from Osama Bin Laden's lair that supposedly showed a closer relationship between Al-Qaeda and Iran than the Obama White House, then conducting backchannel talks with Tehran on halting its nuclear weapons program, wanted known. Nunes, according to a then-close observer, demanded the CIA open up its files for him and Flynn one Saturday. "He was going to sneak up on them" on a weekend, the source snorted, speaking on terms of anonymity to discuss the sensitive incident. Nunes denied that excursion, but said he did go down to Central Command headquarters in Tampa "to meet with the team that was doing exploitation of the documents in 2013."

Related: Michael Flynn's Middle East nuclear woes

He and Flynn seemed to share an obsession with Iran. Nunes concurred with Flynn's insistence that Tehran was involved with the 2012 attacks on the U.S. consulate and annex in Benghazi, and oversaw a two-year investigation into the incident, focusing on what Republicans had portrayed as] the Obama administration's inept responses. But the committee's final report, signed by its then-chairman Mike Rogers, "debunk[ed] a series of persistent allegations hinting at dark conspiracies" and concluded that "there was no intelligence failure, no delay in sending a CIA rescue team, no missed opportunity for a military rescue, and no evidence the CIA was covertly shipping arms from Libya to Syria," according to the Associated Press's account. The report also found no evidence tying Benghazi to Iran. Nunes called it a "whitewash."

The congressman's "nutty" reputation was enhanced in 2013 when he insisted on moving a joint U.S.-U.K intelligence base from England to the Azores, his ancestral home. The $1.2 billion price tag and national security concerns about relocating to such an obscure spot in the mid-Atlantic doomed the effort, according to an investigation by the National Review. But in an early preview of charges that he "cherry-picked" items for his Russiagate memo to undermine the FBI and Justice Department, the Pentagon accused Nunes's staff of manipulating the numbers on the Azores gambit.

No evidence has surfaced that then-DIA Director Flynn, a native of Rhode Island, home to thousands of Azorean immigrants, had anything to do with that affair. But he and Nunes paired up to champion another issue, one that they were right about: whistleblower accusations that U.S. Central Command leaders were manipulating intelligence reports to burnish the Obama administration's record against the Islamic State group. Flynn, according to The Weekly Standard, was annoying the White House with, "assessments that Al-Qaeda had doubled in strength over The preceding two years." Nunes was helping lead a Republican-led joint congressional task force into the issue. At one point, he flew down to CENTCOM headquarters demanding to see documents, according to reports, but "once in Tampa...was denied access to the analysts and their findings, creating further schisms between the parties." The task force ultimately backed up the whistleblower complaints. So did the Pentagon's inspector general.

Nunes and Flynn evidently maintained close ties through the election and beyond, even as Flynn's world was beginning to unravel with questions about his payments from Kremlin mouthpiece Russia Today, secret talks with former Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak and a confidential lobbying contract with a law firm tied to Turkish strongman Recep Tayyip Erdogan. "I talk to Flynn virtually everyday, if not multiple times a day," Nunes told me in the late December 2016 interview. "Seldom there's a day that goes by that I don't talk to Flynn, and especially right after the campaign, directly."

Despite the troubling revelations about Flynn's Turkish deadlings, Nunes accompanied him to a January 18 breakfast at the Trump Hotel in Washington featuring Turkish foreign minister Mevlut Cavusoglu, according to a report in the Istanbul newspaper Daily Sabah. Questioned by U.S. reporters. Nunes's spokesman Jack Langer called the meeting "a large breakfast event" attended by "20-30 ambassadors to the U.S. and about 10 other foreign dignitaries and officials." But the Daily Sabah, which is considered close to the Erdogan regime, contradicted that statement, saying Cavusoglu was the "only foreign leader at the breakfast," which was closed to the press and featured "topics on the U.S.-Turkish agenda." Langer told the fact-checking site Snopes that "if [he did speak to Cavusoglu], it would've been among all the other ambassadors and officials at the event. There was no separate, private meeting."

Flynn's ties to the Erdogan regime may have had a darker side. About six weeks before the elections, Flynn and two business associates attended a secret New York meeting with Cavusoglu and Berat Albayrak, Erdogan's son-in-law and the country's energy minister. Also present: former CIA Director and then-Trump senior adviser James Woolsey. The topic: Plans to kidnap the prominent exiled anti-Erdogan cleric Fethullah Gulen in Pennsylvania and return him to Turkey. The meeting stayed secret until late March 2017, when The Wall Street Journal exposed it. In that account, Woolsey said he had cautioned Flynn and the others not to carry out any illegal operations and reported the discussion to a mutual friend of Vice President Joe Biden. Muller opened an investigation into Flynn's Turkey ties last November, according to multiple reports.

Asked whether Flynn ever discussed the plot with Nunes, his spokesman Langer responded only, "And with this question, Newsweek has completed its transformation into The National Enquirer."

Nunes, meanwhile, was busy defending Flynn and Trump on another matter: the national security adviser's secret conversations with Kislyak. Had the president-elect approved those talks, and did they include promises to reverse the Obama administration's punishment of the Kremlin for its interference in the 2016 elections? In an unusually partisan step, the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, who was supposed to be leading an investigation into Russian subversion and Team Trump, anointed himself one of the administration's leading defenders. Trump and and Flynn, he opined, were "so busy" that they wouldn't have had time to discuss talking to Kislyak.

A Washington Post headline called Nunes's explanation "strange" and printed it in full:

"No, look, I think this whole issue with General Flynn—General Flynn is an American war hero, one of the—put together one of the greatest military machines in our history providing the intelligence to basically eliminate al-Qaeda from Iraq. And he was the national security adviser designee, he was taking multiple calls a day from ambassadors, from foreign leaders and look, I know this because the foreign leaders were contacting me trying to get in touch with the transition team and folks that wanted to meet with President Trump or — President-elect Trump and Vice President-elect Pence."

Nunes could not rescue Flynn from disgrace—or later, special counsel Robert Mueller, with whom the former national security adviser negotiated a guilty plea on a charge of lying to the FBI.

But Nunes's efforts to distract attention from Russiagate didn't cease with Flynn's departure from the administration a year ago. And even his now-famous "midnight run" to the White House weeks later indirectly involved Flynn: According to multiple reports, Ezra Cohen-Watnick, whom Flynn put in charge of intelligence matters on the White House national security council despite his scant, low level experience at the DIA, helped provide Nunes with classified documents that the congressman claimed to show—falsely—as it turned out, that Obama had "wiretapped Trump Tower." That stunt prompted complaints from good-government groups that Nunes had improperly obtained and publicized classified information.

When the House Ethics Committee opened an investigation, Nunes stepped down from his panel's slow-moving investigation into Kremlin election interference. Temporarily. And on the sidelines, critics noted, Nunes was continuing his campaign to deflect questions about Team Trump's contacts with the Russians, which climaxed with the memo to discredit the Justice Department and FBI probes. That was just Nunes's first step, Axios reported. The chairman is preparing as many as five more reports on politically motivated "wrongdoing" at those agencies, as well as the State Department.

Longtime observers of congressional oversight called such activism on behalf of an administration unprecedented. Partisanship has waxed and waned over the years at HPSCI, depending on who held the gavel, said former senior CIA official Larry Pfeiffer, but "we saw nothing compared with what we are seeing with Chairman Nunes, he told Newsweek. "I don't envy our successors at Langley. We didn't call HPSCI, 'The Island of Misfit Toys' for nothing!"

Nunes, said David Barrett, an authority on Congress and the spy agencies, has added to the partisan rancor on the Hill instead of isolating the committee from the political wars, which it needs to gain the trust of the CIA and other intelligence agencies to admit their mistakes. When the intelligence committees become political, he told The New York Times, oversight of the intelligence agencies becomes "just about impossible."

"None has ever been so partisan as the current HPSCI chair," Loch Johnson, a leading intelligence historian at the University of Georgia, told Newsweek. "Worst yet, Mr. Nunes has become Capitol Hill's cheerleader-in-chief for the Trump administration on anything dealing with intelligence."

But is there a point when such partisanship moves beyond cheerleading into obstruction of justice? Nothing prevents the feds from looking into it, says Edward J. Loya, a former prosecutor in the Justice Department's public integrity section. "The DOJ and FBI can initiate an obstruction of justice charge against anyone, including Congressman Nunes," he told Newsweek. But "it would be highly inappropriate for special counsel Mueller to conduct an obstruction investigation about whether Nunes is obstructing Mueller's own investigation. The more appropriate course," said Loya, now in private practice with Epstein Becker Green in Washington, "would be for the DOJ to appoint a different special counsel to review this matter."

Nunes would no doubt denounce such a move as "political." And he might get some traction with the charge, considering that more than seven out of 10 Republicans polled after his memo's release said they believed that "members of the FBI and Department of Justice are working to delegitimize Trump through politically motivated investigations."

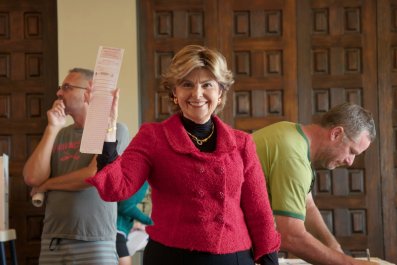

Back in the Central Valley, Janz says he's ready to combat Nunes on Russiagate if he gets the nomination. After all, he says, some of the Trump administration's own officials have been saying that the Russians are already meddling in this fall's elections. He plans to pound Nunes on why he's not focusing on that instead of undermining federal probes into Kremlin subversion.

"The best we can do is speak factually about what is going on..." he said. "All Americans should be alarmed. People in this district are asking why Nunes is going to such great lengths to cover for Trump. There must be some motivation behind what he is doing."