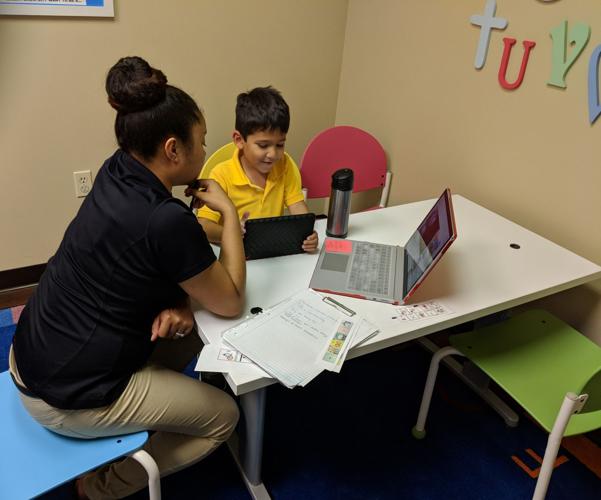

Alejandro Genovesi uses an iPad to build sentences and learn how to pronounce them inside the UCF Communication Disorders Clinic.

Inside a small room decorated like a nursery, Alejandro Genovesi learns to speak English in full sentences by tapping an iPad.

Alejandro is a five-year-old with severe speech delay. He uses the services of the Florida Alliance for Assistive Services and Technology at the University of Central Florida’s Communication Disorders Clinic to improve his speech by using technology.

Alejandro’s father, Joey Genovesi, said the therapy sessions his son receives at the clinic along with the technology used during treatment have helped Alejandro better his speech significantly. He also said that having technology available to help his son at any time feels relieving.

“He used to get very frustrated and he would shut down,” Joey Genovesi said. “Having the tool for him to actually go and find the words gives you relief.”

Researchers at the University of Central Florida and the University of New Mexico have been awarded a grant to conduct a clinical trial that will study how children with severe speech disorders can communicate with the help of technology.

The $2.7 million grant was awarded in June to UCF and UNM by the National Institutes of Health. Researchers will study children aged three to four to develop and evaluate a particular approach to teach children to use communication apps to communicate effectively.

“We have the technology but not a lot of guidance for clinicians, speech language pathologists, teachers or parents to help their children to learn how to use this technology to communicate,” said Jennifer Kent-Walsh, Communication Sciences and Disorders professor at UCF and FAAST Center director.

Nearly 1 in 12 U.S. children ages 3-17 has had a disorder related to voice, speech, language, or swallowing in the past 12 months. The prevalence of voice, speech, language, or swallowing disorders is highest among children ages three-to-six at 11 percent, according to the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Nancy Harrington, speech language pathologist at the FAAST Center, said the study will afford those children who participate with an opportunity to develop their speech that they may not have otherwise had.

“Some of the children that have significant speech impairments and may need to use technology to communicate haven’t had an opportunity to develop those expressive language skills like children with typical developing speech,” Harrington said.

User interface of the Proloquo2Go app. Children who attend the Florida Alliance for Assistive Services and Technology Center at the UCF Communication Disorders Clinic use technology like this to improve their speech.

The clinical trial conducted at UCF in Orlando and UNM in Albuquerque will be divided in two sections.

The first section will have children between the ages of three and four with typical levels of speech understanding for their age.

Within that section, one group will receive a parent instructional workshop to teach them how to use the app with their children.

The second group of children will receive the same workshop as the first group, but will also get ongoing treatment at the clinic to teach them how to build grammatically accurate sentences.

The second section will have the same structure as the first section, but its participants will be children with Down syndrome between the ages of three and four.

The researchers will then look at the length of message that both groups produce. Kent-Walsh said their hypothesis is that the children who get the treatment will produce longer sentences over time. Both trials are expected to last five years.

Cathy Binger, associate professor at UNM’s Department of Speech and Hearing Sciences, said there are two essential ingredients for successful treatment of children with speech disorders: tools to communicate and good instruction techniques.

“You can’t just give children these communication apps and recommend the families go buy them for mobile devices and expect them to be successful,” Binger said. “We also know already that we need to provide them with effective instruction techniques as well.”

Binger, who has worked with Kent-Walsh on research for the past 15 years, said that there will be a high level of coordination between the clinics at UCF and UNM. She said the study will benefit from a larger sample size as a result of having two different locations.

Kent-Walsh said that providing children with speech disorders with adequate instruction is of utmost importance. She said children’s potentials can go untapped without clear guidelines for technologies that help them better their speech.

“These kids have incredible potential but without the appropriate services we don’t see what they’re capable of doing and we’re not helping them continue to develop which is so important with these young kids,” Kent-Walsh said.

One child who is making progress with correct instruction is Alejandro Genovesi. Alejandro used to attend UCP of Central Florida, a school that provides academic curriculums for children with special needs. Aided by the progress made at the therapy he receives at FAAST, Alejandro will enroll in a regular elementary school the next school year.

“Now he will have the iPad with him,” Joey Genovesi said. “We feel that he will be able to be in a regular classroom, and if he does get stuck trying to say something to a friend or to a teacher, he can take the app out and use that to communicate.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.