More U.S. women are dying in childbirth. What can be done?

Safe Start is a home-visiting program created by Philadelphia's Maternity Care Coalition to help pregnant women with limited resources and chronic health problems.

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-pmn.s3.amazonaws.com/public/46BYUN53ENHHJDO3FFOE3SBADE.jpg)

Tamika White almost died of preeclampsia, the pregnancy complication marked by sky-high blood pressure. Her son, born three months premature, almost died, too.

Now, 11 years later, White's job is to help Philadelphia women with the kind of serious medical and social problems she once faced so they can have healthy pregnancies and babies.

White, 35, is a community health worker with Safe Start, a home-visiting program launched two years ago by the Maternity Care Coalition, the venerable Philadelphia nonprofit known for outreach using neon-pink-and-white MOMobiles.

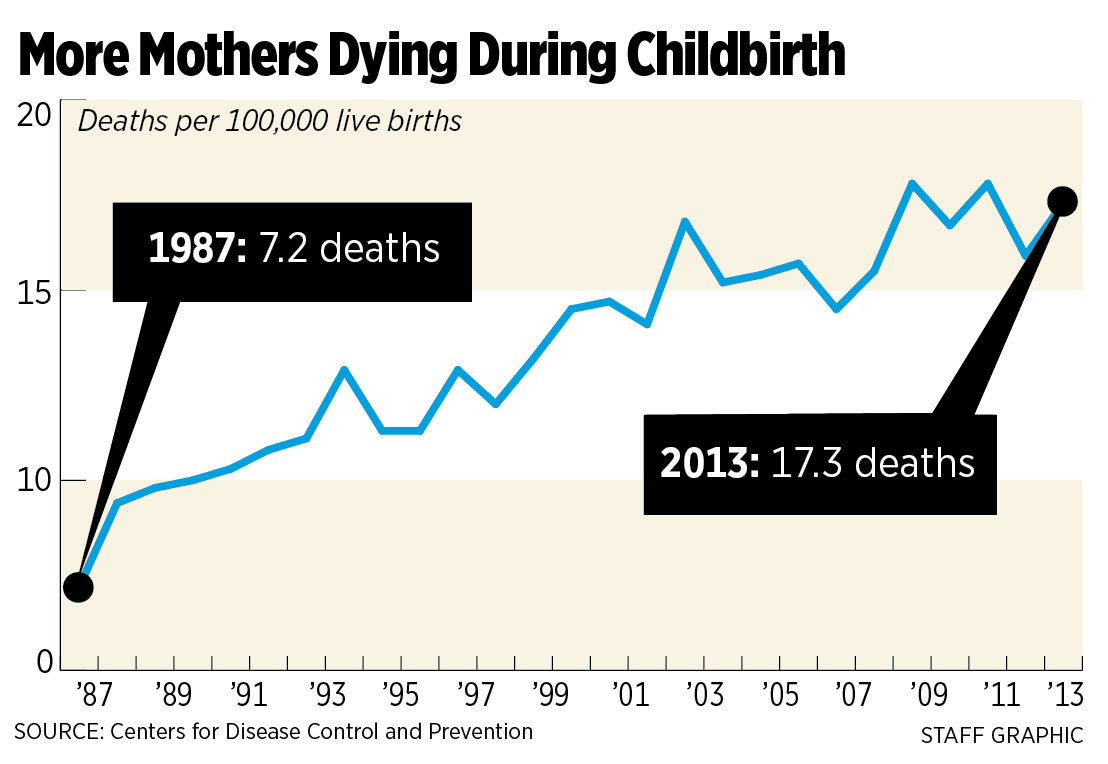

Safe Start, funded by the pharmaceutical giant Merck, is a small but innovative example of efforts to reverse a disturbing trend: While deaths as a complication of pregnancy have been falling around the globe, including in many poor countries, the U.S. maternal mortality rate has doubled since the 1990s. And Philadelphia's rate is even higher than the national average.

Two weeks ago, White visited Candea Atkins, 23; Atkins' longtime boyfriend, Thomas Brown, 20; and their 6-week-old son, Symar. The young parents took turns cuddling and coaxing smiles from the adorable infant as they sat on the steps of the rundown West Philadelphia rowhouse where they live with Atkins' aunt.

Atkins, who grew up in foster care and dropped out of high school, is a Safe Start success story in progress. With White's guidance and goading, Atkins stopped missing her prenatal care visits at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania; quit smoking; controlled her high blood pressure; signed up for free baby formula and food from a state nutrition program; and got baby gear offered by her Medicaid managed-care plan, Keystone First. Both Keystone and the Penn hospital are partners of Safe Start.

"Tamika gave us a lot of help and a lot of relief," Atkins said.

Brown was franker. "If we didn't have you," he said, looking straight at their advocate, "we'd still be struggling."

No easy explanations

Maternal mortality is a complicated issue. Even the definition varies. The World Health Organization counts deaths caused by or related to pregnancy up to 42 days after the pregnancy ends. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tallies such deaths up to a year after the pregnancy ends.

Either way, the U.S. rate has been going in the wrong direction for at least two decades, for reasons that the CDC says are unclear. All told, 700 to 800 U.S. women die every year of pregnancy complications. And tens of thousands of women just narrowly survive childbirth.

Either way, the U.S. rate has been going in the wrong direction for at least two decades, for reasons that the CDC says are unclear. All told, 700 to 800 U.S. women die every year of pregnancy complications. And tens of thousands of women just narrowly survive childbirth.

Far more attention has been paid to fetal and infant safety, with the result that the infant mortality rate has been falling in the U.S. for the last decade. While public health experts applaud that decline, they say the toll on women deserves more scrutiny and resources.

"Every year, up to 300,000 pregnant or postpartum women develop a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, with about 75,000 of them suffering organ failure, massive blood loss, permanent disability, premature birth, or death," declares the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The group advocates federal legislation that would help fund state-based committees dedicated to reviewing and reducing maternal deaths.

Medical errors and ineptitude play a big role in maternal mortality, according to an investigative article published in May by ProPublica, a nonprofit journalism organization, and National Public Radio.

"The fragmented health system makes it harder for new mothers, especially those without good insurance, to get the care they need," the article declared. "Confusion about how to recognize worrisome symptoms and treat obstetric emergencies makes caregivers more prone to error."

Some researchers, however, believe that the U.S. trend has been sensationalized. They say it mostly reflects changes in hospital billing codes and death certificates that have improved the identification of maternal deaths.

In a recent study, K.S. Joseph, a public health researcher at the Women's Hospital of British Columbia, found that the U.S. coding changes coincided with a surge in pregnancy-related deaths involving heart, liver, and kidney disease. Those deaths accounted for almost all the increase in maternal mortality since 1999. At the same time, deaths due to hemorrhage and high blood pressure decreased.

"My analysis suggests that the common perception that the increase is because of poor medical care or disparities in care doesn't hold water," he said. "Any maternal death is a terrible tragedy. But the idea that the U.S. is doing worse than Iran or Saudi Arabia or Libya — that's absurd."

Bette Begleiter, deputy executive director of the Maternity Care Coalition, offered yet another perspective.

"It's not just that we've gotten better at counting," she said. "It's that women are coming to pregnancy sicker. There is an increase in women who are obese, there's the whole opioid crisis, there's an increase in [mental] health problems and partner violence. You can't come up with one protocol to fix it."

The Philadelphia story

Begleiter is a member of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health's maternal mortality review team, which was created — actually, revived after a 40-year hiatus — in 2010 to evaluate an apparent increase in pregnancy-related deaths. (Twenty-nine states, including New Jersey but not Pennsylvania, and a handful of big cities, have such review panels; Philadelphia's is now completing an updated report.)

The Philadelphia team identified 55 women who died within a year of pregnancy from 2010 through 2012. Of these, the panel concluded that 19 deaths were pregnancy-related, and only one probably could have been prevented by better medical care.

Their most striking findings – consistent with long-recognized national disparities – involved socioeconomic and racial factors.

Among the 19 women, 74 percent were African American, 95 percent had Medicaid or no health insurance, 53 percent were obese, 32 percent were high school dropouts, and 15 percent were HIV-positive.

The rest of the deaths were directly caused by drug overdoses, suicide, murder, car crashes, or fires. The reviewers opted not to speculate about possible indirect links to pregnancy. "For example," the team wrote, "it would be impossible to determine with any certainty whether a woman … was killed by her partner because he was upset with her being pregnant."

Armed with the bleak findings, the Maternity Care Coalition brainstormed the concept that would become Safe Start: A hospital obstetric clinic would identify at-risk pregnant women, then offer each of them a Safe Start advocate, a sort of uber-caseworker who would help her access medical, mental-health, and social services. The advocate would forge a close relationship – through home visits, phone calls, texts – and be a liaison to the woman's caregivers and Medicaid caseworker. The advocate would also be trained as a doula, coaching the mom through labor, delivery, and the first six months of new parenthood.

Keystone First, Penn Medicine, and Community Behavioral Health, which provides the city's mental-health and substance-abuse services, gladly agreed to be Safe Start partners. Merck, which has a global initiative to reduce maternal mortality, pledged $1.5 million for three years. Among other things, that covers Safe Start's four advocates, a social worker, and a director.

"The thing that makes Safe Start different, every single woman has an assigned advocate who is face-to-face, providing them support throughout their pregnancy and afterward," said Joanne McFall, market president of Keystone First. "I think part of the problem is that efforts to this point have primarily focused on the health component, but we're having challenges with the issues of poverty — housing, food insecurity, addiction, and recovery."

Echoed Sindhu Srinivas, director of obstetrical services at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania: "The advocates address needs that aren't served in our current system. They are really trying to help women, not just in the moment, but by teaching them self-help skills. The goal is to have these skills translate beyond the pregnancy."

So is it working?

With data from 200 women, the signs are encouraging, said Laura Line, the Maternity Care Coalition's director of strategic partnerships.

The participants missed fewer prenatal care and postpartum appointments than a comparison group of 40 women who chose not to sign up. The participants also had fewer visits to the emergency room, and a lower rate of newborns who needed intensive care. After giving birth, well over 80 percent of the women started breastfeeding and using birth control. Almost 90 percent followed recommendations for keeping their babies safe during sleep.

Anecdotally, some are indeed learning how to help themselves.

"What are your goals now?" White, the advocate, asked Atkins while they met on the West Philadelphia stoop.

"Make sure I get everything together," Atkins answered.

The reply sounded evasive, but as soon as White pressed, Atkins said she plans to go back to school soon to get her diploma — not just an equivalency degree.

"I only need seven more credits to graduate. But it's going to be hard, because if it's night school, we have to find child care, because he'll be at work," Atkins said, referring to Brown, who just got a job at a McDonald's in King of Prussia.

Then the couple shared another plan with White.

"Will you come to our wedding?" Brown asked. "We're going to get married at the Shore next month."