OPINION:

This week, constitutional law experts and the law enforcement community were abuzz after the U.S. Supreme Court added Carpenter v. United States to its docket, a case that could reshape government data collection and the Fourth Amendment in the internet Age. The Fourth Amendment asserts that the “right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated.” Timothy Carpenter, the petitioner in this case, alleges that his Fourth Amendment rights were violated.

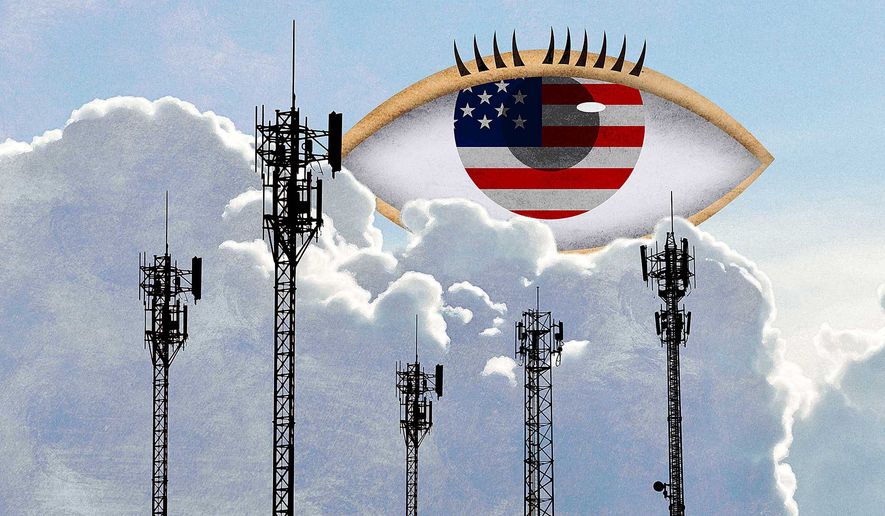

The case comes at a time when domestic surveillance by intelligence agencies is under scrutiny, and smartphone and internet records are playing a greater role in law enforcement investigations. It raises an important legal question about the applicability of old doctrines that give the government immense power in the Information Age.

Carpenter was convicted of taking part in six armed robberies in Michigan and Ohio. The FBI’s evidence at trial included information collected from his cellphone carrier without a warrant, including location information that placed him in the vicinity of the robberies. Police almost certainly could have gotten a search warrant for Carpenter’s phone records. The appeals court upheld his conviction and dismissed his argument because, as most courts hold in these cases, personal information gathered from businesses like phone companies is not a “search” or “seizure” and doesn’t require a warrant.

Before the creation of the web or smartphones, courts developed what’s known as the “third party doctrine” for Fourth Amendment cases. This doctrine denies that information turned over to a third party — like phone call and location information automatically transmitted to a phone company when placing a call — is protected by Fourth Amendment. The doctrine derives from Supreme Court decisions from the 1970s about phone and bank records.

Today, technological advancements mean we each turn over tremendous amounts of personal data to third parties simply with routine use of the digital services of our age. New services that transmit data to the internet cloud, like “smart homes,” voice-activated devices, and Google Docs, offer law enforcement an even bigger treasure trove of personal records that, under the third party doctrine, does not require a warrant to collect.

The mere fact that the Supreme Court agreed to hear the Carpenter case was a small victory for civil liberties groups. The third party doctrine is a blunt instrument that, in our connected world, permits too many low-value “fishing expeditions” by law enforcement. Cellular phone companies in particular are inundated with law enforcement subpoenas every year for user data, including user location. Verizon, for instance, reported that the government issued more than 120,000 subpoenas to the company in 2016 — over 350 per day. Legal teams at Google, Facebook, Amazon and Uber are required to sift through similar government requests for information.

The political right and left have bristled in recent years against intrusive and often secretive government data collection. Conservatives were alarmed when The Wall Street Journal broke news last October that federal agents in Southern California had co-opted state license plate readers and drove around a parking lot to collect information about thousands of gun show attendees. For years, police departments around the country have spent millions acquiring “cell site simulators” that jam cellular signals and collect data from hundreds of nearby smartphone users. Progressives have alleged that these devices are used to identify people at mass protests.

The third party doctrine denies that such information can ever be unreasonably seized or searched. As the Cato Institute argues in its amicus brief in the Carpenter case, it’s time for the court to strip away the decades of privacy doctrine that has permitted police data collection to metastasize.

If the court takes up the Fourth Amendment issues, it should scrupulously apply the Fourth Amendment’s language: Are Carpenter’s phone records “papers” or “effects?” Were they searched or seized? Was the search or seizure unreasonable? Courts ask these questions in other criminal cases, but not when information leaves someone’s home or device. Justice must be served, but the third party doctrine short-circuits what should be a demanding constitutional analysis that protects us all.

Contracts between individuals and phone and app companies affirm the confidentiality of sensitive information, and courts should allow only reasonable searches of that data. We should not relinquish Fourth Amendment protections the moment a third party is involved — especially in an era when devices in our pockets automatically transmit data.

• Brent Skorup is a research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Melody Calkins is a Google Policy Fellow with Mercatus.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.