-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Barbara J Lutz, Mary Ellen Young, Kerry Rae Creasy, Crystal Martz, Lydia Eisenbrandt, Jarrett N Brunny, Christa Cook, Improving Stroke Caregiver Readiness for Transition From Inpatient Rehabilitation to Home, The Gerontologist, Volume 57, Issue 5, October 2017, Pages 880–889, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw135

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

As the population ages, older adults are more often living with functional limitations from chronic illnesses, such as stroke, and require assistance. Because stroke occurs suddenly, many stroke family caregivers in the United States are unprepared to assume caregiving responsibilities post-discharge. Research is limited on how family members become ready to assume the caregiving role. In this study, we developed a theoretical model for improving stroke caregiver readiness and identifying gaps in caregiver preparation.

We interviewed 40 stroke family caregivers caring for 33 stroke survivors during inpatient rehabilitation and within 6 months post-discharge for this grounded theory study. Data were analyzed using dimensional analysis and constant comparative techniques.

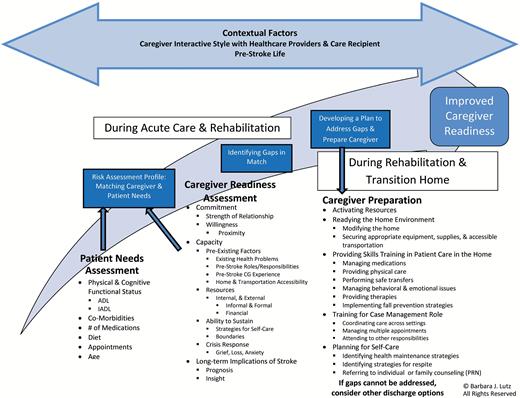

Caregivers identified critical areas where they felt unprepared to assume the caregiving role after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Steps to improve preparation include (a) conducting a risk assessment of the patient and caregiver; (b) identifying and prioritizing gaps between the patient’s needs and caregiver’s commitment and capacity; and (c) developing a plan for improving caregiver readiness.

The model presented provides a family-centered approach for identifying needs and facilitating caregiver preparation. Given recent focus on improving care coordination, care transitions, and patient-centered care to help improve patient safety and reduce readmissions in this population, this research provides a new approach to enhance these outcomes among stroke survivors with family caregivers.

As the population ages, older adults are more often living with functional limitations related to disabling conditions, such as stroke and other chronic illnesses, that require assistance from family members. Approximately 4 million family members in the United States provide care for stroke survivors at home (National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP, 2009).

Stroke is a sudden, traumatic medical crisis for patients and their families. Approximately 970,000 people were hospitalized with stroke in the United States in 2009 (Hall, Levant, & DeFrances, 2012). Although stroke mortality has decreased over the past 5 years due to improved emergency response, stroke remains a leading cause of major disability worldwide. More than 70% of the 6.6 million stroke survivors in the United States report some level of disability from mild functional impairments, such as memory loss or one-sided weakness, to major functional impairments (Mozaffarian et al., 2016). When these patients are discharged home, they need assistance with basic and instrumental activities of daily living (ADL/IADL) from their family members.

The caregiving needs of patients recovering from stroke and other sudden illnesses are different from those of patients with progressive conditions, such as dementia. Stroke occurs suddenly and is overwhelming for family members who are often thrust into the caregiver role within a few days of the event (Lutz, Young, Cox, Martz, & Creasy, 2011; Moon, 2016). In the United States, the average acute care length of stay (LOS) for stroke is 5.3 days (Hall et al., 2012). Approximately 44% of stroke survivors are discharged directly home without inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation services (Bettger et al., 2015). Only about 24% of stroke survivors receive post-acute care in an inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF) where the average LOS is 15.4 days (MedPAC, 2014). Regardless of the inpatient trajectory, the transition home often represents a second, unexpected crisis for patients and their family caregivers (Lutz et al., 2011).

Stroke family caregivers report feelings of uncertainty, emotional distress, and the need for training and information (Greenwood, Mackenzie, Cloud, & Wilson, 2009; Moon, 2016). They are more likely to have depressive symptoms and report fair to poor physical health, higher strain, and are less likely to engage in health promotion activities than noncaregivers (Haley, Roth, Hovater, & Clay, 2015; Pinquart & Sorensen, 2003; Zarit, 2006). Stroke caregivers reporting high strain have higher mortality rates (Perkins et al., 2013). These caregiver health issues can have a negative impact on stroke survivor outcomes (Hayes, Chapman, Young, & Rittman, 2009; Perrin, Heesacker, Hinojosa, Uthe, & Rittman, 2009). Caregivers need assistance in learning strategies to address their changing needs and prevent the detrimental effects of caregiving over time (Cameron & Gignac, 2008; Greenwood et al., 2009).

Our previous work documents how inadequate care giver preparation creates a second crisis for stroke survivors and their family caregivers as they transition home (Lutz et al., 2011) and describes specific caregiver domains that should be systematically assessed prior to discharge (Young, Lutz, Creasy, Cox, & Martz, 2014). The purpose of this study was to develop a theoretical framework for improving stroke caregiver readiness that is grounded in the experiences of stroke family caregivers. The framework can serve as a foundation to better understand the needs of stroke caregivers and survivors and help identify gaps in caregiver preparation across the care continuum.

Design and Methods

In this grounded theory study, we analyzed 81 interviews with 40 stroke family caregivers caring for 33 stroke patients. The study was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited from two inpatient rehabilitation facilities in the southeastern United States and enrolled in the study after providing informed consent. English-speaking caregivers of stroke survivors who had a diagnosis of first ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, and goal of discharge to home were included in the study. Medical record data including age, sex, ethnicity, type and location of stroke, and functional independence measure (FIM) were collected for each stroke survivor. The FIM has 18 items in 6 domains related to cognitive and motor function. Total scores can range from 18 (totally dependent) to 126 (totally independent) (Keith, Granger, Hamilton, & Sherwin, 1987; Oczkowski & Barreca, 1993).

Interviews were conducted by members of the research team which included two experts in grounded theory and three doctoral students trained in qualitative interviewing and grounded theory. Interviews lasting 60–90min were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Although the focus of the study was on the caregivers’ experiences, participants were given the choice of which family members to include in the interview. In some cases, the stroke survivor and/or more than one primary family caregiver were present for the interviews.

Consistent with a grounded theory approach, our methods and sampling evolved over time as we became sensitized to the transition issues faced by stroke family caregivers (Charmaz, 2006). In the first phase, we interviewed 19 care givers (caring for 15 stroke survivors) during inpatient rehabilitation and within 6 months of discharge (30 interviews). Caregivers indicated they felt inadequately prepared as they transitioned into the caregiving role full-time at home. We identified that caregivers were not systematically assessed for their readiness to assume the caregiving role during the stroke survivor’s stay in inpatient rehabilitation, resulting in caregivers feeling overwhelmed and unprepared at home. Based on this preliminary analysis, in the second phase of the study, we interviewed 21 additional caregivers (caring for 18 stroke survivors) during inpatient rehabilitation, and at 1 month and 3 months post-discharge to better capture the transition effects (51 interviews).

The interview questions also evolved over this time. The initial interview questions were open ended, focusing on anticipated post-discharge needs. During the follow-up interviews, we asked caregivers about their post-discharge experiences and how well prepared they felt for the care giving role. The interview questions became more focused as we identified specific areas that affected the caregiver’s ability to provide care for the stroke survivor. For example, some caregivers indicated that their health affected their ability to provide care. In response to this preliminary finding, we added questions that probed for any health concerns, such as back problems, cardiac issues, anxiety, or depression, that might influence the caregiver’s ability to provide care.

Data Analysis

The theoretical framework described here is based on analysis of 81 interviews that were conducted with the 40 care givers from 2008 to 2012. The interviews were imported into NVivo 10 (QSR International, 2010) for data management and analysis.

Data were analyzed using dimensional analysis (Bowers, 2009; Schatzman, 1991) and constant comparative analysis (Strauss, 1987; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Dimensional analysis is based on symbolic interaction and involves line-by-line open and focused coding to help the research team identify and track the experiences of study participants and factors that contribute to participants’ understanding of their experiences (Bowers, 2009; Schatzman, 1991). Initially, we used open coding to better understand the caregivers’ perceptions of their needs as they moved through the care continuum, and how these translated into a sense of being prepared (or ready) for the new caregiving responsibilities once they were home. As salient dimensions were identified, focused and theoretical coding was used to further explore relationships among and across existing categories (Charmaz, 2006). We also explored provisional findings with new study participants as a way to substantiate their salience with the developing theoretical framework. Constant comparative analysis was used to compare and contrast dimensions within and across the interviews and the literature to help further refine the domains of care giver readiness (Strauss, 1987; Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

An interprofessional research team, consisting of the study investigators and graduate students from nursing, rehabilitation counseling, psychology, and public health, analyzed the data, and developed and revised the evolving framework. The research team met weekly to discuss the ongoing analysis. They kept an audit trail of written field notes and memos documenting study findings and tracking methodological and substantive decisions made during the analysis. Preliminary versions of the model were presented at several venues including two support groups with stroke caregivers and two conferences with stroke nurses and rehabilitation case managers. Feedback from participants helped us to verify and refine concepts during model development. The final framework illustrates components of improving caregiver readiness from the perspectives of study participants. Participant demographics are included in Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| . | Mean . | Range . | N (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregivers (N = 40) | |||

| Age | 60.6 | 23–89 | |

| Female | 29 (72.5) | ||

| Relationship to stroke survivor | |||

| Spouse | 27 (67.5) | ||

| Adult child/child in-law | 12 (30) | ||

| Mother | 1 (2.5) | ||

| Stroke survivors (N = 33) | |||

| Age | 68.5 | 33–84 | |

| Male | 21 (63.6) | ||

| Admission FIM | 45 | 18–73 | |

| Type of stroke | |||

| Ischemic | 24 (72) | ||

| Hemorrhagic | 5 (15) | ||

| Unclassified | 4 (13) | ||

| Ethnicity—caregivers and stroke survivors (N = 73) | |||

| African American/Black | 13 (18) | ||

| White | 57 (78) | ||

| Other | 3 (4) | ||

| . | Mean . | Range . | N (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregivers (N = 40) | |||

| Age | 60.6 | 23–89 | |

| Female | 29 (72.5) | ||

| Relationship to stroke survivor | |||

| Spouse | 27 (67.5) | ||

| Adult child/child in-law | 12 (30) | ||

| Mother | 1 (2.5) | ||

| Stroke survivors (N = 33) | |||

| Age | 68.5 | 33–84 | |

| Male | 21 (63.6) | ||

| Admission FIM | 45 | 18–73 | |

| Type of stroke | |||

| Ischemic | 24 (72) | ||

| Hemorrhagic | 5 (15) | ||

| Unclassified | 4 (13) | ||

| Ethnicity—caregivers and stroke survivors (N = 73) | |||

| African American/Black | 13 (18) | ||

| White | 57 (78) | ||

| Other | 3 (4) | ||

Note: FIM = functional independence measure.

Participant Demographics

| . | Mean . | Range . | N (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregivers (N = 40) | |||

| Age | 60.6 | 23–89 | |

| Female | 29 (72.5) | ||

| Relationship to stroke survivor | |||

| Spouse | 27 (67.5) | ||

| Adult child/child in-law | 12 (30) | ||

| Mother | 1 (2.5) | ||

| Stroke survivors (N = 33) | |||

| Age | 68.5 | 33–84 | |

| Male | 21 (63.6) | ||

| Admission FIM | 45 | 18–73 | |

| Type of stroke | |||

| Ischemic | 24 (72) | ||

| Hemorrhagic | 5 (15) | ||

| Unclassified | 4 (13) | ||

| Ethnicity—caregivers and stroke survivors (N = 73) | |||

| African American/Black | 13 (18) | ||

| White | 57 (78) | ||

| Other | 3 (4) | ||

| . | Mean . | Range . | N (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregivers (N = 40) | |||

| Age | 60.6 | 23–89 | |

| Female | 29 (72.5) | ||

| Relationship to stroke survivor | |||

| Spouse | 27 (67.5) | ||

| Adult child/child in-law | 12 (30) | ||

| Mother | 1 (2.5) | ||

| Stroke survivors (N = 33) | |||

| Age | 68.5 | 33–84 | |

| Male | 21 (63.6) | ||

| Admission FIM | 45 | 18–73 | |

| Type of stroke | |||

| Ischemic | 24 (72) | ||

| Hemorrhagic | 5 (15) | ||

| Unclassified | 4 (13) | ||

| Ethnicity—caregivers and stroke survivors (N = 73) | |||

| African American/Black | 13 (18) | ||

| White | 57 (78) | ||

| Other | 3 (4) | ||

Note: FIM = functional independence measure.

Results

Caregivers described their overall experiences with stroke as a series of life changing transitions from the initial event, through their hopes for recovery during inpatient rehabilitation, and finally to the realization once they were discharged home that “life [would] never be the same.” It was apparent in the interviews that there were important gaps in the preparation the family received and ultimately how “ready” they were to assume care post-discharge. These gaps only became evident once the stroke survivor was discharged home and the family member assumed the care giving role full-time; “When he came home—I was reeling for weeks. My mind was just going a hundred different directions. I had no idea it was going to be as hard as it was because I’m here by myself.” Some of these gaps were merely bothersome; “I didn’t get enough information. I think I should have been sent home with extra urinals, bed pads, gloves, masks, diapers.” However, other gaps were overwhelming and sometimes put both the stroke survivor and caregiver at risk; “I thought I killed him because he wasn’t doing really well, and then when the ambulance came to take him out, that was the first clue that we were really unprepared to be caregivers… completely unprepared.”

These experiences illustrated the gap in assessing and addressing caregiver readiness to meet the care needs of the stroke survivor as they transitioned home, resulting in issues post-discharge. Based on the analysis of the interviews, we developed a framework for improving caregiver readiness (Figure 1) illustrating the three-step process for assessing and preparing the family caregiver for assuming the care giving role. The steps include (a) conducting a systematic risk assessment of the dyad, which includes assessing the patient’s needs and the caregiver’s commitment and capacity to address those needs; (b) identifying and prioritizing gaps between the care recipient’s needs and caregiver’s readiness; and (c) developing a plan to address the gaps. This process is described in detail in the following paragraphs.

Conducting a Risk Assessment

This assessment has two parts that should be completed simultaneously during acute care or early inpatient rehabilitation phases of the stroke trajectory. These are (a) assessing the patient’s needs and (b) assessing the care giver’s commitment and capacity (i.e., readiness) to meet the patient’s needs.

Assessing Patient Needs

The patient needs assessment includes evaluating the patient’s physical and cognitive functional status, ability to participate in basic and instrumental activities of daily living, comorbidities that may affect function and recovery, medication regimen, dietary requirements, number and types of appointments that will be required post-discharge, and age. This type of patient assessment is conducted during the inpatient stay by the rehabilitation team. This information is included in the patient’s medical record and is used by the rehabilitation team to determine the type of care and assistance the family caregiver will need to provide at home and to develop the discharge plan.

Assessing the patient’s needs is standard of care in inpatient rehabilitation, but a parallel and systematic assessment of the caregiver’s readiness to provide necessary care, as well as the long-term implications of stroke on the family unit, is not generally conducted. This comprehensive assessment is the first step in improving caregiver readiness and is described briefly here, and in more detail in a previously published article (Young et al., 2014). The assessment has two main components: caregiver commitment and caregiver capacity.

Assessing Caregiver Commitment

Caregiver commitment includes the strength of the care recipient/caregiver relationship and the willingness of the caregiver to provide post-discharge care. The strength of the care recipient/caregiver relationship includes evaluating how connected the caregiver and care recipient are and identifying existing issues in the relationship. These issues often become more visible in times of stress and crisis post-stroke. “It would be terrible for me, in this situation, if I didn’t love my husband.”

The caregiver’s willingness, confidence, and comfort in shifting into the caregiving role and providing care must be assessed. “I don’t care how much help or aid I have to give her because, I mean, that’s a spouse’s job, obviously.” The degree of intimacy involved in caregiving is also an important consideration.

Even in cases where the caregiver and care recipient relationship is strong and the caregiver is willing, geographic proximity must also be assessed. For example, if an adult child lives in another town or state, relocating to provide care for a parent may not be feasible.

Assessing Caregiver Capacity

Caregiver capacity includes assessing the following three domains: preexisting factors, availability and accessibility of resources, and the caregiver’s ability to sustain the role over the long term. An assessment of preexisting factors includes (a) preexisting physical and mental health concerns, such as back, knee, joint, or cardiac problems, and depression, anxiety, or other mental health concerns; (b) pre-stroke roles and responsibilities, including other care giving responsibilities, work, and other existing roles that may compete with the new caregiving role; and (c) accessibility of the home environment, including transportation.

Careful assessment of the caregivers’ health is important in understanding their abilities to assume both the physical and emotional tasks related to caring for someone post-stroke. Existing health conditions that may be exacerbated by increased stress or physical demands that affect strength and stamina or cognition can affect the caregivers’ ability to assume the caregiving role. These issues should be identified early in the stroke recovery trajectory so that appropriate resources can be identified and activated.

It isn’t that I don’t have a desire to [take care of my husband]…but I physically can’t do that… It would have broken my heart for him to start to fall and I know I can’t physically catch him because it would have destroyed my [back] surgery.

Preexisting roles and responsibilities also must be considered. Caregivers were often working, caring for other dependents, and managing other daily tasks. Adding the new responsibilities of caring for the stroke survivor was often problematic. This is especially critical for adult children who find themselves in the role of caring for their own children and a parent who has had a stroke, while balancing their own personal and professional lives.

You know, the kids who are at home with us, we don’t see them. We come in, we bring some groceries in or some kind of damn fast food and that’s it. The little guy is starting to really go like, “How come Grandpa is more important than me?”

Identifying these responsibilities early and assisting care givers in figuring out how to manage the existing roles with the new one are critical for improving readiness.

Caregivers in our study who had previous caregiving experience had some idea of what to expect during rehabilitation and post-discharge. For those who had realistic expectations about what the care recipient would need and their own capacity to meet those needs, previous caregiving experience was helpful. Others with previous experience often had unrealistic expectations about what they could take on post-stroke and found themselves overwhelmed without adequate help when they got home. “Now that I’m a caregiver, even though I’m a nurse, I find that I have absolutely been mind-boggled by how much work there is, how much you need to learn…”

Home and transportation accessibility is another critical area of the caregiver assessment. In most cases in the United States, pre-discharge in-home assessments are no longer conducted. Instead, therapists rely on caregivers to describe the home environment and bring in photos, a video, or measurements of the main living areas so they can identify issues with home accessibility. Stairs, narrow doorways and halls, and small bedrooms and bathrooms all make home accessibility difficult. Many homes are not equipped with ramps, or grab rails in the bathroom, and often have carpeting which makes using a wheelchair or walker more difficult, as this caregiver discussed during the pre-discharge interview:

Our house is not handicapped accessible. We have steps leading into our front door, without rails. We have small bathrooms. I’m going to have to rearrange furniture. We have a room that is a sunken room that has steps that are fairly steep.

During the follow-up interview, she indicated she hired a “rehabilitation engineer” to assist her with home renovations to improve accessibility. In most cases, caregivers realized during the pre-discharge interview that they only had a few days to have ramps, new flooring, and safety equipment installed. These time limitations add to an already stressful situation.

So we weren’t really prepared and we wished it could have been at least another week before he came home so we could have had a chance to set things up and had some of the stress taken off of us.

Transportation accessibility is another important concern. In some cases, caregivers had to purchase a new, more accessible, vehicle while the stroke survivor was in inpatient rehabilitation. “I don’t have a vehicle that can carry a wheel chair.”

The second important domain of a comprehensive assessment of capacity is evaluating the family’s internal and external resources. These include the types of informal and formal supports, and financial resources available to caregivers and care recipients.

Caregivers described informal supports as being critical to their success. These included family members, neighbors, friends, and members of their church communities or other social networks. Informal networks provided both tangible and emotional support. “My neighbors said they are all going to get their schedule and make a listing and come over even if it’s for only an hour, so I can go to the grocery store.” Those caregivers who had limited access to these types of informal support resources found themselves without anyone to call if they needed assistance such as having someone stay with the care recipient so they could go to the store, an important appointment, or for respite.

Formal resources include tangible supports that are available through the health care and social support system. For our study participants, these included Social Security Insurance, disability insurance, elder services, food stamps, transportation services, Medicare, and Medicaid.

Financial resources were often a problem for caregivers, especially if they did not have adequate insurance to cover medical costs, or if either the caregiver or care recipient was working prior to the stroke and needed that income for daily living expenses. “Well I’m anticipating bankruptcy because I don’t see any way out of it…bills have gone unpaid simply because I don’t have the money that I had when I was working part-time.” Limited financial resources placed added stress on these already overwhelmed caregivers. They often found they did not have enough funds to cover medications, food, gas, or other expenses once they got home.

Assessing the caregiver’s ability to sustain the caregiving role long-term by exploring existing strategies caregivers have for their own self-care, determining what types of support (such as respite) caregivers may need, and identifying ways to maintain or improve these strategies was also important. The caregiver’s overall psychological and emotional response to the stroke experience should also be assessed, as stroke is a crisis event for everyone involved (Lutz et al., 2011). Stroke caregivers described feeling overwhelmed, isolated, and alone once they got home. “I felt like I was a little old Eskimo woman that they put on this ice block, chopped it off and sailed it out in the middle of the ocean.”

The impact of stroke, the long-term implications on the family, and the family’s expectations for recovery should also be considered.

It’s just never going to end… And so it’s not a case of waiting for the weekend to get a break, it’s not a case of waiting for the fever to break. He’s the same today as he was yesterday and the same tomorrow and the same next week. …This could be forever.

Identifying and Prioritizing Gaps, Developing a Plan

Once the risk assessment is completed and gaps in caregiver readiness are identified, the next steps are prioritizing areas of primary importance for addressing the stroke survivor’s post-discharge needs and developing a plan to address the gaps to help the caregiver become prepared. Strategies in this step include identifying and activating resources, readying the home environment, providing skills training to meet day-to-day needs, training for the case management role post-discharge, and planning for self-care.

Identifying and Activating Resources

Caregivers in our study described how overwhelmed they were with all they had to learn and do to prepare for the caregiving role during the inpatient stay. They also indicated they often did not know what to expect when they got home because they had never experienced anything similar to the stroke event, “I think the important thing for me, as a caregiver, is to know what to expect. The good, the bad, and the ugly…I don’t even know what to expect.”

One of the most overwhelming tasks was prioritizing needs, and then identifying and activating resources to meet those needs. Applying for government financial support and/or food assistance, setting up help at home, getting the correct prescriptions filled, securing powers of attorney, or trying to get authorization to communicate with the care recipient’s primary care provider could be overwhelming. Accomplishing all of these tasks was left to the already overburdened and stressed caregivers, who were usually given a list of phone numbers to call to try to activate these resources. In order to get authorization for needed services or to set up appointments, many caregivers found themselves calling and leaving messages or trying to navigate through multiple automated voice prompts with little success, adding frustration.

Then, the prescriptions that I brought into the pharmacy, a lot of them were higher doses than what was actually regulated, like his Plavix. He was supposed to be getting a double dose because he had the stents put in. Well, they wouldn’t authorize the double dose of it, and then nobody could get in touch with the doctor. Nobody from [the facility] called [the pharmacy] back to say anything –and basically I was just told, “Hey, you have him home, not our problem anymore.”

The caregivers also needed to identify informal supports including friends and family who might be willing and able to help them run errands or fix a meal when they got home. Having a network of support was even more beneficial. “He’s got a good network of friends. They’re begging for ways to help...I would say we’ve have more help than the normal [family].”

Without this type of organized informal support, care givers had difficulty managing all of the new responsibilities. For example, just going to the grocery store or pharmacy became difficult if the care recipient could not be left alone. Self-care, such as keeping a medical appointment or even getting a haircut, became impossible for many care givers because they had to be “on duty” 24/7. “He had to be watched 24 hours around the clock …this is absolutely impossible to do that he cannot be left alone.”

Readying the Home Environment

Getting their homes ready for the newly disabled stroke survivor was also difficult. Caregivers often had to find contractors to install ramps, replace carpeting with hard flooring, install hand rails and high toilets, widen doorways, and remove furniture so that a hospital bed could fit in a room that may have previously been a dining room or guest room. In one case, the spouse caregiver and her daughter had to find and move into a larger apartment during the 2 weeks that the stroke survivor was in inpatient rehabilitation. In another case, the caregiver had hard surface flooring installed throughout the entire house the week before the stroke survivor was discharged.

Caregivers needed assistance early in the stroke trajectory in anticipating and planning for these changes, and securing appropriate and affordable equipment, supplies, and services, including accessible transportation. Assessing insurance coverage and helping the caregiver identify ways to secure needed services that may not be covered were also important. When these issues were not addressed prior to discharge, caregivers often faced additional frustrations when they got home and were not able to secure equipment and supplies that were necessary for the recipient’s care.

I started calling [after we got home] and I found out that, “Oh, you know, the insurance won’t cover it, so you’re on your own.” I couldn’t get oxygen. I couldn’t get anything. The only thing I could do was get his prescriptions.

These types of experiences left the caregivers feeling abandoned and alone with nowhere to turn for help.

Skills Training to Meet Day-to-Day Needs

Most inpatient rehabilitation facilities provide training for family members prior to discharge, which many caregivers found to be very helpful. “The thing I like about [rehab] is making you learn to do a bed transfer to a wheelchair.” However, sometimes these skills did not translate well to the home, creating safety issues for the stroke survivor and caregiver, as described by this caregiver during a post-discharge interview:

We got out of the car and I figured I’m just going to transfer him into the chair; it’s no big deal, right? His knees were so weak, and the chair that they had given me was a light, featherweight chair… the floor in our garage was so slick, even though the wheels were all locked, it slid away from the car with his hand on it. He fell between the wheelchair and the car seat.

Medication management was particularly difficult and confusing for some caregivers and could result in the stroke survivor receiving the wrong dosage, frequency, or type of medication. When speaking about administering her husband’s medications, this caregiver describes the situation as follows:

One [pill] was the littlest bit more yellowy and this other one was the littlest bit more blush looking and then I had to cut one of them in half and then you got a half of this little bit. And I said, “I’m scared to do this, because I’m afraid I’m going to give him the wrong thing.”

Training for Case Management Role

One of the most overwhelming roles caregivers assumed post-discharge was that of case manager. They described coordinating the stroke survivor’s care across settings and making decisions about which services would best meet the care recipient’s needs. They set up and coordinated multiple appointments with primary care providers, neurologists, and outpatient therapies. They also negotiated with insurance providers, government support services, and other service providers. “I didn’t have like an ombudsman to go to because I was concerned. I had put two and two together to figure I needed a handicap parking sticker but there was nobody I knew to ask ‘well how do I get it?’”

An often frustrating challenge for caregivers and care recipients when they finally got home was the number and timing of follow-up appointments. These were often scheduled early in the morning, multiple days a week. For example, one caregiver discussed getting up at 5:00 a.m. to get her husband ready for 9:00 a.m. appointments, which were 45min away, 3 days a week. Others spoke of having one specialist appointment early in the morning and another in the middle of the afternoon. Having to get the care recipient ready for the appointment (toileted, bathed, dressed, and fed) and then transferred into and out of the car multiple times in 1 day was physically and emotionally exhausting.

Another important aspect to improve caregiver readiness was assisting caregivers in identifying and coordinating other responsibilities. Managing work schedules was one of the biggest issues for caregivers who were not retired. In some cases, caregivers needed to arrange for family medical leave with their employers. Once this was established, a change in discharge date had detrimental effects on the care givers’ employment, even to the extent that the caregiver was not available. Expectations that caregivers would be available to come into the IRF for frequent training or assist with the stroke survivor’s care often added burden to an already stressful time.

I’m like, listen, we have five kids at home. We have a business. We’re struggling just to get [to the IRF] to see what’s going on and try to help the situation. There is no way that we can stay here over night. There is just no way.

Caregivers suggested having someone they could call with questions and who could help them prioritize, manage, and complete these multiple tasks, especially when they first got home. “They need one person you can call with a question…they really need a point person for each patient or family saying, ‘If you’ve got questions, here’s the one to call’ because then you know I could get answers as I go along.”

Planning for Self-care to Enhance Sustainability

Caregivers were often so overwhelmed with their new responsibilities that they found it difficult to care for themselves. Furthermore, they were just beginning to realize the impact the stroke has had on the care recipients’ and their lives. As they moved through the stroke trajectory, they were so focused on the stroke survivor, anticipating and preparing for the discharge, that they did not have time for the “reality” of stroke to set-in. Also, during rehabilitation, many of these caregivers still hoped and expected that the stroke survivor would return to pre-stroke function. When this did not happen, many of the caregivers described (in post-discharge interviews) having to learn to adapt to this “new life” and integrate all of the changes into their daily lives. “You have to redesign your entire life; I mean, literally, life will never be the same.”

Across our interviews, participants indicated that no one discussed the possibility of family counseling. The psychologist in the IRF often spoke with family members about the impact of stroke on the stroke survivor, describing the changes in cognition and neurological function, but family counseling for the purpose of transitioning to their new lives and reconciling the grief and loss of future plans was not included in the plan of care.

Contextual Factors

In addition to the steps outlined above to help improve caregiver readiness, several important contextual factors were identified. First, it is important to take into account the caregiver’s interactive style with providers and with the care recipient when developing a plan. Some care givers were more direct, outspoken, and persistent in identifying and communicating their needs and expectations, whereas others were quite passive, expecting that rehabilitation professionals would tell them what they needed to know (Creasy, Lutz, Young, Ford, & Martz, 2013). Second, caregivers indicated that it is important to understand the caregiver/care recipient dyad’s pre-stroke life and their goals and preferences regarding their post-stroke lives. Family units in this study varied in their understanding of the prognosis and how that affected their future plans.

Discussion

Many stroke patients are discharged home with functional limitations requiring assistance with ADL and IADL. This assistance is usually provided by family members who often feel unprepared or “unready” to assume the caregiving role. Moreover, many caregivers describe feeling abandoned and alone with no one to turn to post-discharge. These findings are supported in other studies and reports focusing on the needs of stroke survivors and caregivers as they are discharged home (Cameron & Gignac, 2008; Cameron, Tsoi, & Marsella, 2008, Moon, 2016).

The Improving Stroke Caregiver Readiness Model is grounded in the experiences of stroke family caregivers and provides a family-centered approach to better identify needs and assist caregivers with preparation. The model can be used to help researchers and practitioners identify potential gaps in readiness and develop tailored interventions for stroke survivors and their caregivers as they move through the stroke trajectory. Just as we routinely assess the patient’s progress through the stroke recovery trajectory, the caregiver’s progress also needs to be systematically and regularly assessed. This assessment would provide the basis for prioritizing needs (Lutz et al., 2011; Young et al., 2014).

Caregivers in this study often did not realize what they needed or what skills and training they were lacking; in essence “they didn’t know what they didn’t know,” until they got home and found themselves unprepared to meet the stroke survivor’s needs. In post-discharge interviews, they described wishing someone had assisted them before discharge in anticipating the skills they would need at home and developing strategies to plan, organize, and manage the caregiving responsibilities. They also needed help in activating resources during inpatient rehabilitation so they would have adequate support when they got home. Similar anticipatory guidance strategies have been recommended in other studies and reports (Ostwald, Godwin, Ye, & Cron, 2013; Moon, 2016).

A recent scientific statement from the American Heart Association identified Class I, Level A evidence that care giver interventions which “combine skill building with psycho-educational strategies” (p. 2843) and are individualized to the needs of the caregiver are most effective for improving caregiver and stroke survivor outcomes (Bakas et al., 2014). Referrals to family counseling that include problem solving and positive coping strategies may also help stroke survivors and their family members adapt to their new, post-stroke lives (Cheng, Chair, & Chau, 2014).

This type of family-centered approach to stroke care is particularly timely given the focus on improving care coordination, care transitions, and patient-centered care to help improve patient safety, enhance outcomes, and reduce hospital readmissions (Coleman, Boult, & American Geriatrics Society Health Care Systems Committee, 2003; Institute of Medicine, 2001). However, the opportunity to work with family caregivers during an inpatient stay is often limited making coordinated, seamless care transitions difficult. Shortened inpatient stays usually do not provide ample time for family members to learn what they need to know to assume the caregiving role (Cameron & Gignac, 2008; Cameron et al., 2008; Lutz & Young, 2010; Lutz et al., 2011, Moon, 2016). Assessing caregiver readiness during the inpatient stay and providing immediate follow-up at home to assist caregivers in developing new skills and translating skills learned in inpatient rehabilitation to the home environment is critical. Poorly prepared caregivers present a safety risk for patients and caregivers and may increase preventable readmissions. If gaps in caregiver readiness cannot be addressed, other temporary or long-term options that provide more support should be considered.

Additionally, there were no published tools that systematically assess stroke caregiver readiness. In a recent review of transitional care interventions in stroke, only 6 studies out of 44 reviewed included caregiver outcomes (Bettger et al., 2012), and none evaluated the caregiver’s readiness to provide care. There are several validated tools to assess caregiver burden and other caregiving outcomes (Deeken, Taylor, Mangan, Yabroff, & Ingham, 2003); however, they are not designed to assess caregiver readiness to adequately meet the stroke survivor’s needs, while maintaining self-care and attending to other responsibilities. Our model can be used as the basis for developing tools to address this gap.

Limitations

It is important to consider that this model was developed with data from interviews with 40 stroke caregivers at two inpatient rehabilitation facilities in the southeastern United States. and therefore may not be generalizable to other care giver populations. In order to verify the applicability of the model, it has been presented in several national venues and verified with stroke caregivers and members of several stroke support groups in other regions. Additional research using this model as a framework for caregiver assessment and intervention studies and with other caregiving populations should be conducted to test its wider applicability.

Conclusion

The Improving Stroke Caregiver Readiness Model builds on our understanding of the experiences of stroke family caregivers during and after inpatient rehabilitation. In this article, we advance our understanding of the phenomenon of stroke caregiving by combining patient and caregiver assessments into a risk assessment of the dyad (stroke survivor and caregiver), and by looking at how the rehabilitation team might better help the dyad prepare for the challenges of discharge home. The intent of enhancing caregiver readiness is to mitigate the second crisis of stroke into a manageable transition, by identifying potential gaps as family members assume the caregiving role, and tailoring interventions before, during, and after rehabilitation.

In order to minimize caregiver burden and improve outcomes for stroke patients and their family caregivers, we must consider the family unit and individualize care plans to address their specific needs. The critical first steps in this process are to conduct a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s needs and, equally important, the caregiver’s readiness to assume the caregiving role. This will allow us to identify gaps and prioritize interventions that are appropriately tailored to the needs of the family to ensure appropriate family-centered care.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (R15NR009800, R15NR012169).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the stroke survivors and family care givers who openly shared their stories. This research would not have been possible without their participation. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Author notes

Decision Editor: Barbara J. Bowers, PhD