-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mary Burke, The Cottage, the Castle, and the Couture Cloak: ‘Traditional’ Irish Fabrics and ‘Modern’ Irish Fashions in America, c. 1952–1969, Journal of Design History, Volume 31, Issue 4, November 2018, Pages 364–382, https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/epy020

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In the 1950s, Irish fashion exports that combined native lace, linen, and wool with fashionable cuts or palettes were marketed to Americans as a continuation of vaguely defined ‘old traditions’. In the case of woman designer-dominated Irish couture, the transformation of ‘peasant’-made textiles into luxury offerings was harmonized with an image of an entwined ‘plebeian’-‘patrician’ heritage. This effaced the origins in Famine-relief projects for poor females of the craft industries upon which mid-century Irish fashion relied. The promotion of Irish labels at American department-store level often occurred with the aid of Irish government agencies and state entities such as the national airline, whose improved flight-times in the 1950s aided in making the Irish fashion season a trade pit-stop. In addition, a symbiotic relationship developed between female celebrities with Irish links such as Grace Kelly and Jacqueline Kennedy and quality Irish garments in which the cachet of one reinforced that of the other. If one also considers the role played by tourism authority Bord Fáilte Éireann and the Irish Export Board, then the era’s fashion export trade was of a continuum with the same decade’s state-encouraged quality tourist goods market. Ultimately, such ‘traditional’ offerings actually functioned as a shop window for a government eager to advertise Ireland’s economic modernization. Indeed, the industries of aviation, tourism, brewing, crystal manufacture, advertising, film, couture, crafts, and textiles worked with state bodies to symbiotically cement an international image of Ireland that centred on the making, selling, and marketing of heritage and designer goods. Despite dizzying seesaws between signifiers of ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’, mid-century Ireland was neither fully ‘traditional’ in the way promised to tourists nor evenly modernized. Thus, the female-dominated workforce for Irish couture, clothing manufacture, and home knitting was simultaneously exploited and a harbinger of Irishwomen’s growing autonomy.

The post-war boom that fuelled the Irish-American fantasy of ‘return’ to bucolic Ireland was encouraged by the developing tourist industry, since Americans spent disproportionately in comparison to continental and British visitors.2 To that end, when tourism authority Bord Fáilte Éireann was established in 1955, the marketing of quality native goods became its focus in promoting Ireland internationally. Officials rejected kitschy shillelaghs and leprechauns, and the sudden availability in 1950s Ireland of high-end products masquerading as simple ‘traditional’ souvenirs speaks to the plan’s success.3 Concurrently, even as cheaper cotton and synthetics were displacing storied natural fabrics in the rapidly globalizing home market, Irish fashion exports utilizing native lace, linen, and wool were shrewdly marketed in North America or to U.S. tourists as a continuation of vaguely defined ‘old traditions’.4 The promotion of ready-to-wear clothing carrying Irish designer or designer-manufacturer labels at American department-store level often occurred with the aid of Irish government agencies and state entities such as Aer Lingus (as detailed under the subheading ‘State agency promotion’). If one considers bodies such as Bord Fáilte and Córas Tráchtála (the Irish Export Board) as boosters of things Irish to international consumers, then the era’s fashion export trade can be seen as of a continuum with the state-encouraged quality tourist goods market. Ultimately, and for all the references to ‘tradition’, such offerings functioned as a shop window for a government eager to advertise Ireland’s economic modernization and openness to international markets.5 Nevertheless, the demands of promotion required the fantasy of a sealed, uninterrupted Irish past.6

Castles and cottages: Selling Irish fashion in post-war America

The craft industries upon which Irish fashion relied were rooted in historical trauma. The Victorian-era Irish textile and lace industries that created goods for the whole United Kingdom market had generally originated in post-Famine relief projects encouraged by the Congested Districts Board and elite patronesses.7 Famine-era needlecrafts and textile production were explicitly cast as relief projects for poor women.8 Nevertheless, later iterations of Irish lace, embroidery and tweeds effaced that catastrophe’s disruption by implying that such skills were rooted in a seamless past. The marketing of extant textile businesses ‘established either in the aftermath of the Famine’ or ‘under the Congested District Board’, such as Magee of Donegal (f. 1866), airbrushes out the context that underdeveloped Donegal was decimated by the 1840s Famine, with relief projects laying the roots for its post-war success as a centre of handweaving.9 Thus, the true ‘heritage’ of Irish needlecrafts and textiles was not palatable to the average consumer.

Clothing promoted explicitly as ‘Irish’ in the 1950s and 1960s, be it mid-market Aran knits, couture, or quality ready-to-wear, often combined handwoven textiles with fashionable cuts or palettes.10 Nevertheless, marketing and fashion magazine copy and photography generally emphasized what was termed ‘tradition’ over modishness. This sleight of hand deflected from the fact that any ‘heritage’ aspect of Irish fashion garments generally lay in their textiles rather than their design: there was no traditional Irish clothing, only traditional Irish fabric.11 The centuries-old Irish linen trade and the long history of textile firms such as Magee and Avoca (f. 1723) speak to a continuity absent from the history of Irish clothing: the only originally native garments left by the late Victorian era were the western island of Aran’s woven belt (crois) and báinín (an undyed flannel wool jacket, named for its fabric).12 The Aran hand-knit, a seemingly deeply-rooted craft item central to post-war fashion offerings, was credited with paving the way for the ensuing export success of Irish couture and quality ready-to-wear.13 However, it had a surprisingly late evolution, since it was an early twentieth-century adaptation of the ganseys of British fishermen brought to Aran by the Congested Districts Board.14 Its history as domestic-market commodity is even more recent: In 1930, Muriel Gahan, an organizer of the Irish Countrywomen’s Association, founded in 1910 in the cultural nationalist spirit of rural improvement, began to sell Arans in her Dublin outlet for cottage-made products. The style was also sold in that decade by O’Máille’s, a Galway shop that helped popularize Irish tweeds in the US by clothing male cast members of 1952’s The Quiet Man.15 In addition, the Aran jumper’s history as ‘Irish national costume’ and global-market commodity is most recent of all, originating in Aer Lingus’s 1950s marketing to America.16 Indeed, the Irish national airline flew Arans by heritage label Cleo (f. 1936) to Los Angeles over Christmas 1959 in time for a Marilyn Monroe film.17 By 1960, the Irish hand-knit look was influencing Paris couture woollens.18

In the case of Irish couture, the transformation of ‘peasant’-made textiles into luxury offerings was harmonized with an image of an entwined ‘plebeian’ and ‘patrician’ heritage, effacing the peasant-patroness power dynamics of Famine relief projects. This was particularly true of Sybil Connolly (1921–1998), widely credited with initiating the Irish fashion export invasion. Connolly’s ‘coming-out’ for influential American buyers and journalists was staged in 1953 in Dunsany Castle in Meath, at the invitation of her domestic client, Lady Dunsany.19 (Two-thirds of Connolly’s domestic clients ‘live[d] in castles.’20) The era’s Vogue editor records that she and her cohort were drawn to Ireland, a ‘completely unexpected’ centre for fashion to everyone but Harper’s Bazaar editor-in-chief Carmel Snow, by Connolly’s collection of Irish tweed and linen garments.21 Gahan’s ‘cottage’ shop was housed in a Georgian edifice in Dublin’s St. Stephen’s Green, an architectural style and a site associated with the urban eighteenth-century Protestant elite.22 In a similar manoeuvre, Connolly’s couture was showcased by juxtapositions of the patrician and the rustic, the castle and the cottage, and the contemporary and the pre-twentieth-century. For instance, Connolly’s couture iteration of the purportedly ‘traditional’23 Kinsale hooded cloak for a 1953 Life cover was modelled by the socially prominent Anne Gunning, daughter of a Sussex landowner. (The image has become visual shorthand for Connolly-era Irish couture.24) The accompanying spread, partially shot at Dunsany Castle, featured the daughter of the 19th Baron of Dunsany as well as Gunning, resplendent in a ‘relatively low’-priced $400 ball gown ‘embroidered by Donegal cottagers’ earning the equivalent of $25 per week.25 As the Economist’s obituary for the designer noted, a modernizing Ireland was sold to women ensconced within ‘the limousines of New England and Hollywood’ as one of ‘white-washed cottages’, ‘black shawls, [and] the hooded cloaks…of old Donegal’. Strikingly, these visuals resembled the images used contemporaneously in Irish tourism marketing and in The Quiet Man, suggesting the global circulation of such signifiers.26

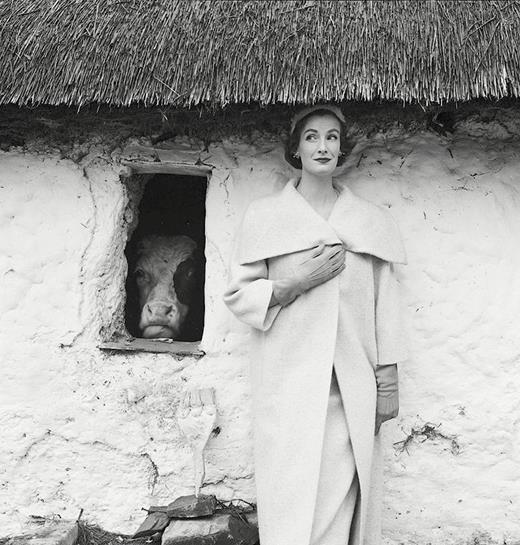

This fantasy was not necessarily appreciated at home: writing of couture embellishments talked up as ‘ancient’ Irish style, the Irish Times wryly noted that the ‘legendary ladies of Ireland’ were ‘apparently…great people for jewel embroidery on their ballgowns.’27 Moreover, a celebrated Irish satirist mocked Connolly’s ‘unusual amalgam of myth and new invention’ in a U.S. interview in which she discussed the Donegal handweavers in her pay toiling in a cottage ‘lit only by an oil-lamp’.28 However, American fashion journalists ‘warmed to every suggestion of an unspolit’ Ireland29 and such visions likely influenced the manner in which Connolly’s clothes were framed in the fashion press. A Norman Parkinson photograph, shot ‘in one of Ireland’s most magnificent Georgian rooms—part of the Provost’s Palace of Trinity College in Dublin’ for a March 1954 Vogue, features a Connolly couture linen skirt described as possessing ‘hand-embroidery patterned after a detail of Georgian architecture.’ (This emphasis was derided by subsequent Irish Times references to ‘pseudo-Georgian…fancy dress’ fashion creations.30) In contrast to the anglicized elite’s magnificent old university, a modest backdrop is utilized in the quirky facing-page shot of Wenda Parkinson, the photographer’s wife, who models Connolly outside a whitewashed thatched byre as a cow looks out from the structure’s small, glassless window [1]31. The structure looks strikingly clean and possibly newly thatched, recalling that the aforementioned satirist seemed particularly amused by Connolly’s description of her handweavers’ ‘spotlessly clean’ and whitewashed cottage, a treatment he called out as ‘quite obsolete’.32 In short, there is an unmistakable overlap between Connolly’s eulogizing and the visual created for Vogue: both offer a rustic picturesque excised of cow manure and true rural underdevelopment’s unphotogenic dishevelment.

Norman Parkinson shot of Sybil Connolly wool coat, 1954 Vogue magazine. Wenda Parkinson, the wife of photographer Norman Parkinson, models a Sybil Connolly white Irish wool coat outside a thatched cow byre. The image illustrated a feature on Dublin in the March 1954 issue of Vogue. Photo courtesy of the Norman Parkinson estate.

Read as a whole, the collections of Connolly and her peers suggest many juxtapositions of ‘castle’ and ‘cottage’: Women’s Wear Daily records that the former utilized a replica of the ostensibly ‘timeless’ Tara Brooch33 in a show at Philadelphia department store Gimbel’s in 1953. Connolly also created caps inspired by thatched cottages for a 1954 collection,34 the year that Tipperary designer Irene Gilbert showed a tweed suit in America that was named for an exclusive Anglo-Irish hunt club.35 In Connolly’s fantasy, Bord Fáilte-compatible Ireland,36 a full-length couture skirt may be called ‘Victoria’, while a ‘billowing quilted’ evening garment can be inspired by the red flannel petticoats of Connemara, 37 a former Congested District decimated by the famine for which ultra-nationalists blamed the very monarch honoured!38 In similar aethesticizations of historical poverty and colonization, rival designer Raymond Kenna’s 1958 ‘Man of Aran’ suit was appliquéd with an islander and his donkeys carrying turf to his whitewashed cabin, while his 1955 ‘mantles’ were inspired by the ‘Norman invasion’ of Ireland.39 In short, the troubled, impoverished colonial past is flattened out into a depoliticized source of aesthetic inspiration in which no distinction is made between colonizer and colonized, elite and peasant. Responding to the attractively repackaged Ireland of Irish designers, an August 1954 Vogue spread on Limerick featured both a ‘late Georgian country pile’ and a ‘modest’ farmhouse.40 The Ireland of peers and peasants was having a fashion ‘moment’: an advert for a full-length green evening coat in a 1955 Vogue issue uses a harp as backdrop, a patrician instrument that is the heraldic emblem of Ireland.41 Moreover, the label ‘Irish’ in reference to natural fabric, in particular, was briefly so recognizably a signifier of upmarket style that it was even appropriated by 1950s American designer-manufacturers whose linen may not have actually been Irish!42

Irish fashion and the social rise of Irish America

The rise of Irish hand-knits and couture and the native-textile apparel exports that came in their wake speaks to the deterritorialization of ‘Irishness’ due to both emigration and globalization. It occurs in tandem with the mid-century Kennedy- and Princess Grace-era social rise of Irish-America, which also relied on the effacement of historical trauma: historian Mary C. Kelly argues that Irish-American progress from tenement to mainstream evolved within a complex course of amnesia regarding the famine and poverty that had often spurred Irish emigration. Such amnesia paved the way for the broader American public’s previously unthinkable acceptance of an Irish-American Catholic president as the progressive face of the future.43 Kelly’s analysis suggests that the era’s potentially conflicting images of a simultaneously traditional and forward-thrusting Irish America was harmonized by Irish fashion exports utilizing contemporary cuts and traditional fabrics.

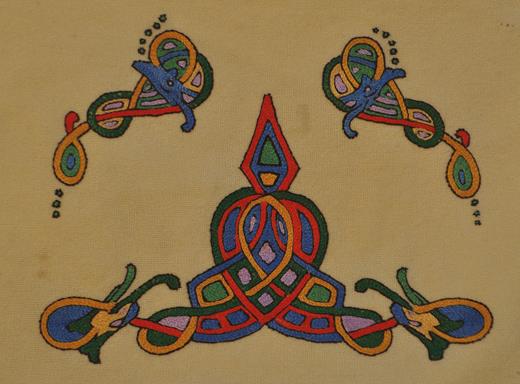

In addition, a symbiotic relationship developed between female Irish-American celebrity and quality Irish garments in which the cachet of one reinforced that of the other: A young Princess Grace of Monaco was photographed by Howell Conant skippering a small sailboat in Monaco Harbour whilst wearing an Aran sweater and later commissioned Irish lace Gilbert dresses. Moreover, Néillí Mulcahy (1925–2012) came to attention when her aunt, the wife of the Irish President, wore her designs on an official visit to the United States in 1959. Furthermore, Anjelica Huston, a dual citizen of Ireland and America, was photographed in 1969 in Ireland by Richard Avedon for a 24-page Vogue spread. Avedon’s extravaganza utilized Connollyesque backdrops of ‘tinker’ wagons, bogs, haystacks, castles, and round towers. Additionally, in her official White House portrait, Jacqueline Kennedy wears a finely-pleated linen gown by her personal friend, Sybil Connolly [2].44 In part because of such attention, American altruism took on the cause of native ‘womanly’ crafts as early as 1954, when Gahan persuaded the Kellogg Foundation to endow the Irish Countrywomen’s Association with an Edwardian estate for use as an education centre for traditional crafts.45 This was exactly the kind of juxtaposition of grand setting and ‘modest’ product exalted in the period, and underlines the role played by American support of Irish traditions. These trends collide in a decorative báinín cushion cover [3] embroidered in the mid-1960s under the remit of a Galway Irish Countrywomen’s Association guild. The handmade creation juxtaposes storied ‘high culture’ (the illuminated manuscript-style Celtic interlace) with the ‘folk’ (the undyed flannel).

Jacqueline Kennedy in a pleated Irish linen Sybil Connolly gown. Aaron Shikler’s oil on canvas official portrait of First Lady Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy depicts her wearing a pleated gown in fine Ulster handkerchief linen by her personal friend, Sybil Connolly. The Irish designer used nine yards of this linen to make every one yard of the pleated fabric. The portrait was placed on public display in the White House in 1971. Photo courtesy of the White House Historical Association.

Mid-1960s ICA craft project: Book of Kells-inspired embroidery on undyed Irish flannel wool. Zoomorphic Celtic interlace inspired by the Book of Kells, an Irish early Christian illuminated manuscript of the Gospels, embroidered on báinín (undyed flannel wool) cushion cover by Catherine Burke in the mid-1960s under the remit of the Kilcoona, Co. Galway guild of the Irish Countrywomen’s Association (ICA). Collection of the author.

I will briefly digress to note that given the globalization of both fashion and Irishness, it is no surprise that this Irish ‘moment’ also influenced British designers with Irish links and American customers. Paris-trained designer John Cavanagh (1914–2003) liked to claim he’d been born in Mayo in the period, though he was possibly London-born. Cavanagh used ‘real Irish lace’ in his breakout spring 1952 collection and later created wedding gowns for members of the extended British royal family on the strength of such work.46 Likewise, Dublin-born London designer, Digby Morton (1906–83) received coverage in Life for his 1953 ‘inva[sion]’ of the American market with Donegal tweed ready-to-wear and was soon advising Dublin fashion graduates to utilize ‘wool…and linens printed in Celtic-inspired designs’. Morton had been showing under his own name since 1934 and had never overtly exploited his origins, but went on to feature Aran-‘inspired’ handknits for the first time in his 1955 autumn show in London, garnering Vogue’s attention.47

Fashion and the selling of Ireland to American tourists

By 1959, Irish knitwear designer Maureen Evans (‘the Balenciaga of hand-knits’) was making a good living selling modernized Arans to American tourists,48 signifying the manner in which Irish ‘crafts’ and couture melded at times. The social arrival of Irish America and the concurrent evolution of Ireland’s national airline and its duty-free offerings meant that Americans of this descent grew familiar with Ireland’s high-end goods. Increased post-war contact with the ‘motherland’ cemented the novel association of things Irish with elite taste and readied the broader U.S. market for the ensuing success of Irish-textile ready-to-wear into the late 1960s. The tourist ritual of shopping for quality ‘native’ goods when visiting Ireland had emerged as early as 1947, when the world’s first duty-free shop was created at Shannon Airport. This occurred after the inaugural Ireland-US Air Services Agreement permitted U.S. flights to the western seaboard Shannon Airport alone, leaving Dublin Airport out of the lucrative American tourist trade.49 (The subsequent rise in satisfied Irish-American visitors funnelled through that airport and onto semi-state body-developed bus tours50 is reflected by the popularity of the given name ‘Shannon’ in the US after 1960.51) 1947 was also the year in which a pair of Czech immigrants revived Waterford Crystal, which became one of most successful high-end indigenous offerings for tourists. Waterford had ceased production in 1853, although its marketing implies an uninterrupted history by stressing its eighteenth-century founding.52

When juxtaposed, seemingly random facts reveal how state agencies, the tourism industry, and manufacturers strategized with producers of quality clothing to sell Ireland. For instance, Mulcahy and Gilbert designed the Aer Lingus Irish wool and linen uniforms of the 1950s and 1960s in order to transform hostesses into ‘officers of good will for Irish products’. Meanwhile, travelogues for the U.S. tourist market share narrative features with that showcase for Irish tweeds, The Quiet Man. Additionally, Connolly used Waterford Crystal as inspiration for a shimmering robe, and staged a shoot at Bunratty Castle, an attraction for American tourists flying into Shannon that was restored in the 1960s by art dealer John Hunt. In turn, Hunt’s wife, Gertrude, backed 1960s designer Kay Peterson, herself a former manager of Shannon’s duty-free shop and a trade advisor at Córas Tráchtála’s Regent Street office in the mid-1950s. (Evans credited Peterson as the first to promote Arans as ‘high fashion’.) Similarly, an Aer Lingus co-sponsored ‘Charm of Ireland’ fashion and Waterford Crystal promotion in Philadelphia was staged in a replica of Bunratty, and Connolly called her Dublin boutique-cum-townhouse ‘a shop window for Ireland’ in the American press.53

Thus, in mid-century Ireland, the industries of aviation, tourism, brewing, crystal manufacture, advertising, film, couture, crafts, and textiles appeared to work with state bodies to symbiotically cement an international image of Ireland that centred on the making, selling, and marketing of heritage and designer goods. Indeed, any internationally-known aspect of Irish culture could be recruited in the cause of fashion sales, since collection titles often referenced famous locales or literature.54 In its heyday, Irish fashion was understood closer to home as the antithesis of ‘“whiskey, leprechauns and shamrock[s]”’.55 Nevertheless, due to cross-promotion, seemingly unrelated industries and cultural attractions lived happily together in an Ireland-shaped box in the American consumer mind. To wit, the jostle of mass-market and high-brow and avant-garde and historic in Vogue’s mash-up of things newsworthy in the Ireland of 1954:

The rush of road-building, of housing…Michael Scott…designer of Dublin’s new glass and concrete bus station…[t]he return to making the famous Waterford glass…Sybil Connolly…the giant Guinness plant…the Blarney Stone…John McGuire[‘s]…textile-printing mill…Ashford…hotel and castle…used for filming The Quiet Man…the stained glass …designed by Evie Hone…a book of criticism of Catholic authors…[and]…[t]he plans for the Yeats Memorial…56

Thus, it is almost unsurprising that although Mulcahy won the Aer Lingus uniform design contract in 1963, she had already named a tweed suit for the national carrier in 1955.57

‘New colors, age-old in Ireland’: Textile firms respond to ‘American needs’

The Technicolor-enhanced landscape of The Quiet Man disseminated the image of a colour-saturated rural Ireland to American consumers.58 Not coincidentally, the contemporaneous Irish textile industry began experimenting with more vibrant colours in direct response to ‘American needs’.59 By the late Victorian period, the once-bright clothing of the West of Ireland poor had dulled,60 and the notion of bright ‘peasant’ homespuns emerged from Dublin’s early Abbey Theatre, which located a ‘native exotic’ in the peasant West:

The color of the peasants’ costumes were generally drab, either grey or black, but the Abbey Theatre heightened these realistic colors by adding the bright woven colors of the wools from the western part[s] […]. They were able to take this license since spinning and weaving were important industries on the islands, and occasionally one saw vivid colors in the local dress (emphasis added).61

This (re)invention of tradition was reinforced in the 1920s by the introduction of coloured wools at Avoca, subsequently described as having been inspired by the ‘unmistakable pinks, blues, purples and greens of the surrounding heather’.62 By contrast, that mill’s Famine-era blankets for the British Army and the local workhouse had been dyed only grey, white, or red.63 Likewise, although Irish lace had traditionally been produced in a muted palette, Connolly commissioned shades such as lime green and pink for an early 1960s evening dress collection. She also commissioned pastel shades of tweed from Magee, which Snow publicized because Magee textiles had heretofore tended towards the ‘masculine’ and utilitarian.64 It is a measure of Connolly’s knack for self-promotion that she implied that her use of ‘native’ fabrics and colours and her modernization of tweeds was unprecedented and specific to Ireland. However, Morton had introduced pastel-coloured and fashionably-cut women’s tweeds in the 1930s, and Gilbert had worked with Magee on ‘feminine’ colours in advance of Connolly.65 In addition, Cavanagh’s use of ‘real Irish lace’ occurred one year before Connolly’s breakout and just before Gilbert’s domestic client, Lady Rosse, asked for found Connemara wool to be dyed red,66 which suggests that the shade was novel. At any rate, the truism of Irish textiles as bright and/or reflective of the landscape is cemented in post-war U.S. fashion journalism67 and remains oft-repeated.68 Bold colour was particularly emphasized in the case of 1960s Irish designers, such as Peterson, wishing to move on from Connolly’s formality and reappropriations of capes and Connemara skirts.69 Thus experimentation with bright dyes—which spoke to modernization and sensitivity to market demands—was sold as tradition. Such sleights of hand contributed to Life’s confusing description of Connolly’s use of ‘new colors, age-old in Ireland’.70 Indeed, as a result of such emphases, sometimes the shallowest of signifiers denoted ‘Irishness’: Princess Grace wore what was called a ‘lime-green’ Givenchy dress for lunch with President Kennedy in May 1961, but in the words of a widely-reproduced Associated Press report, the garment’s colour had transformed into the Hibernian shade of ‘emerald’ and a ‘gesture for Ireland’ when worn again on an official Irish visit one month later.71

Unstitching Irish economic history: fashion and women’s textile and apparel production

Despite dizzying seesaws between signifiers of ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’, the reality was that Ireland was neither fully ‘traditional’ in the way promised to tourists and Quiet Man fans nor evenly modernized. Thus, the female-dominated workforce for Irish couture, clothing manufacture, and home knitting can be seen both as exploited and as harbingers of Irishwomen’s growing autonomy. On the one hand, and in an echo of Victorian Irish lace’s ‘fair trade’ origins, low wages in a still-developing Ireland meant that mid-1950s Irish couture prices had, in Life’s cynical words, ‘as much charm as Irish styles.’72 ‘Nearly all’ mid-century couture or expensive ready-to-wear garments were sold abroad because ‘few Irish could afford them’.73 (This echoes the Victorian period, in which handmade Irish lace was worn only by the Irish and British elite.74) Unsurprisingly, a 1960–61 survey of the woollen industry by the government-sponsored Committee on Industrial Organisation concluded that ‘peasant’ handwovens had become ‘a luxury product’.75 Indeed, the vast majority of Irish women in the 1950s, including workers in handmade lace and woollens and the assemblers of Connolly’s eveningwear, themselves wore factory-made or locally-tailored clothing.76

Conversely, between 1949 and 1969, foreign trade out of Ireland rose from £191 million to £961 million. However, the popular version of Irish economic history runs that the reforms of the government’s First Programme for Economic Expansion in 1958 halted the post-independence (post-1922) search for a national identity and economy rooted in ‘tradition’. Thus, the story goes, a recessionary country suddenly enjoyed a minor export boom in clothing and other goods, while processes of liberalization, urbanization, and secularization surged.77 However, this narrative does not give enough credit to the success of the female-dominated Irish fashion business from the early 1950s, which was a bellwether for overall post-war growth and for Irishwomen’s increasing autonomy. This progress was exemplified by the wildly successful Connolly, who became a global celebrity member of the jet-set in her own right.78 Connolly alone employed over 100 women to weave and crochet in the 1950s.79 When we consider these and the many other women working at home and in factories who made or finished the couture and ready-to-wear garments, textiles, and lace designed and/or ordered by Connolly, Mulcahy, and Gilbert, it’s clear that the fashion boom benefitted Irishwomen with few economic avenues.80 Indeed, a government-commissioned study of the era revealed that on many farms in the Irish-speaking West, the main household income actually came from the wife’s knitting rather than farming.81 The contradictions of a thrusting export industry fuelled by the labour of women that, nevertheless, relied on images of ‘premodern’ Irish womanhood is revealed by the press coverage of the unmarried Connolly. American journalists emphasized the seemingly startling fact that she was self-made, while reverting to descriptions of her attractiveness that relied on the stereotype of the decorative ‘Irish colleen’.82 In modernizing Ireland, however, Connolly was an unalloyed paradigm of female independence since her sister and female secretary were her only business partners83 and her trail-blazing was lauded in the Irish Senate years before the economy’s official take-off: her work was cited as an exemplar to be emulated by manufacturers in a 1954 debate on standards for Irish exports.84 Thus, the early 1950s success of Connolly and her female-dominated industry spearheaded economic modernization in a way that is often uncredited; male-centred and male-authored Irish economic histories often overemphasize 1958 and underemphasize the apparel industry and women’s paid piecework in the home.

State agency promotion and the mid-century Irish fashion trade

As noted in the introduction, a further overlooked aspect of the triumph of Irish fashion exports was the role played by uncelebrated government bureaucrats. Prior to the creation and success of Córas Tráchtála (f. 1951), the complacent native manufacturing scene had enjoyed ‘a captive market and high tariff walls’.85 Soon, however, the textile industries were stimulated by the Export Board, which encouraged use of heritage fabrics by international designers for ‘county’ garments, discouraged imitation of foreign design, and provided funding to manufacturers of identifiably ‘Irish’ clothing.86 The subsequent global outlook of the native sector is suggested by a perusal of the October 1957 issue of Dublin lifestyle magazine, Creation (f. 1956), whose opening twenty pages are dominated by adverts for businesses such as Country Wear (‘now at selected stores here, England, Canada, the U.S.A., Bermuda’) and ‘Irish Elegance,’ a collaboration between Dublin manufacturer Duff and Gilbert.87 Moreover, Creation’s spreads of the era (including one shot at Dublin Airport!88) feature Irish designers such as Kenna and Gilbert as prominently as international labels such as Nina Ricci and Lanvin.

In addition, Córas Tráchtála co-sponsored (sometimes with Aer Lingus) high-impact promotional events for native-fabric ready-to-wear clothes at American department stores. It also provided practical assistance to designers and manufacturers such as subsidized airfares, fashion press advertising, and secretarial services, to the envy of participants from other nations at pan-European trade shows held in the US.89 Irish designer ready-to-wear of the period was sold in American department stores such as Gimbels, Macy’s, Altman, I. Magnin, Wanamaker’s, Filene’s, and Lord & Taylor,90 and the latter purchased over $1 million worth of major Irish labels for its 1963 ‘Pride of Ireland’ event.91Vogue’s 1954 International Fashions Issue headlined ‘USA, France, England, Italy, Spain, Ireland’, Dublin couture shows were covered in the American press, and Macy’s advertised their 1960 replica ‘Paris, London, Dublin, [and] Madrid couture originals.’92 Such visibility ensured that the de facto Irish fashion season became a trade pit-stop, not least because of improved Aer Lingus flight-times between London and Dublin as of 1954.93 Filene’s sales manager visited ‘Dublin, Paris, Rome, London, Florence and Barcelona’, while the buyer for Toronto’s best department store (Eaton’s) would fly to London, Paris, and Dublin, where she purchased both Connolly and the Country Wear Irish tweeds of designer-manufacturer Jack Clarke, Connolly’s mentor.94 On the flight home to Dublin might also have come a designer-manufacturer such as Jimmy Hourihan, who by the 1960s was able to take a state agency-subsidized promotional trip of up to six weeks in a dozen North American cities in the lead-up to St. Patrick’s Day.95

In an interview with Hilary Pratt, who revived Avoca textile mills after its post-1960s slump, the businesswoman graciously ‘name-checks all the state agencies which helped’, while her interviewer credits ‘genius’.96 This is an amusing example of this tendency to overlook the role government agencies played in the post-war Irish fashion and textile export scene. The origins of such intervention are buried under the widely-disseminated legend of Connolly’s bedazzling of American fashion journalists in 1953. To wit, the real beginnings of Connolly’s international success lay in the fact that in August 1952, Córas Tráchtála had brought fifty envoys of the influential Philadelphia Fashion Group to Dublin to see her collection for Clarke’s Dublin retail outlet, Richard Alan.97 Nevertheless, popular accounts of her stellar launch tend to credit the glamour of the Dunsany Castle show a year later or her subsequent Life cover over the banality of state agency promotion.98 Likewise, by 1954, the New York Times was covering Gilbert’s first American fashion show, ‘held under’ Irish government sponsorship, and by 1956 the designer possessed a lucrative pattern service in America.99 Things Irish dominated the British fashion press reports of 1955, and a Times article reported that Gilbert’s London show used Avoca handwoven tweed. However, equally interesting was its easily-overlooked titbit that three British designers were utilizing Irish linen that season ‘at the request of [promotional body] the Irish Linen Guild, who would like more Englishwomen to use this fabric for dresses’.100

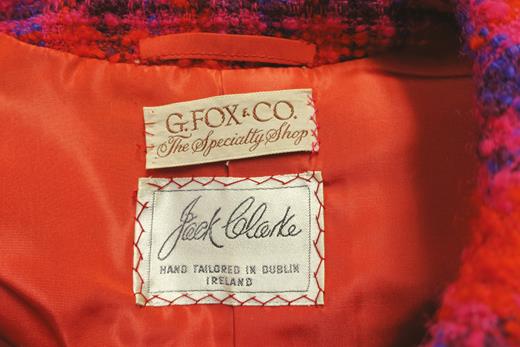

An important booster of Irish couture in the American fashion press was the aforementioned Snow, who was also Cleo’s North American agent and the Dublin-born daughter of a head of a late Victorian Irish textile export company.101 Thus, Snow embodied the very real links between earlier Irish textile and crafts promotion and the mid-century trade. Diana Vreeland’s role in the Irish fashion scene in America has had less attention: she was mentored by Snow, advised Jacqueline Kennedy regarding her wardrobe, and orchestrated Huston’s Irish shoot.102 Moreover, Hourihan recalls that the strong support for Irish fashion exports of Altman’s department store in the 1950s and 1960s was due to the Irish links of executives John Burke Snr. and Jnr. The significance of such personal connections is suggested by the provenance of a 1958 fuchsia, purple, and blue plaid wool Jack Clarke suit [4], which was purchased at G. Fox & Company. This Hartford, Connecticut department store sold the Jack Clarke label in the post-war period and its chief executive from 1938 to 1965, Mrs. Beatrice Auerbach, was a personal friend of the Clarke family who stayed with them in Ireland.103 Popular retellings of the success of Irish fashion downplay the role such state agency promotion and cross-Atlantic, cross-generational connections played, instead favouring the mystique that it was simply the sudden and warranted international recognition of Irish talent. Of course, meaningful contact was only possible due to transportation improvements: the national airline’s upgraded routes conveyed Aran handknits destined for Hollywood and Irish designers en route to department store promotions in one direction and American fashion buyers in the other. Such traffic exemplifies how broader economic development aided and was aided by the era’s fashion export success.

1958 Jack Clarke suit sold by G. Fox & Company, Hartford, Connecticut. This 1958 red, fuchsia, purple, and blue plaid wool Jack Clarke suit, sold by Hartford, Connecticut department store, G. Fox & Company, was owned by Eleanor Hotte, who taught Costume Design at UConn’s School of Home Economics in the late 1960s. Photo and details courtesy of Prof. Laura Crow and UConn’s Costume and Textile Collection.

State intervention contributed to the cultural capital of Irishness in post-war America, but more tangible benefits also accrued: Irish wool exports doubled by 1955, and Córas Tráchtála’s 1958 report concluded that the previous year had seen sales of ready-to-wear exports rise from £458,000 to £788,000. Meanwhile, total domestic and overseas sales of Irish clothes rose from £3 million in 1958 to over £10 million by 1965.104 Such figures suggest that ready-to-wear and a raw material of fashion rather than labour-intensive couture proper seem to have been particularly profitable. Exports by designer-manufacturers such as Clarke, Henry White, and Jimmy Hourihan, some of whose labels boasted the terms ‘hand tailored’ or ‘handwoven’ [5;8], likely benefitted from the cachet of Irish couture, whose unique selling point was often its utilization of handmade native textiles and lace. By 1957, 75% of Connolly’s gross earnings of $500,000 per annum came from North American sales. Similarly by 1963, Gilbert’s domestic couture business, established in the early 1950s, accounted for less than 40% of her profits, with the rest coming from her newer business of ready-to-wear exports to North America.105 This indicates that, as in Connolly’s pioneering case, Gilbert’s ready-to-wear exports likely piggy-backed upon the aura of tradition and luxury endowed by a term (‘handwoven’) previously used of her more rarefied creations. Additionally, protections still in place prior to Ireland’s preparations for joining the E.E.C. in 1973 also kept Irish clothes distinctive, and, thereby, profitable, since up to 1965, Irish-made garments using synthetic fibres were liable to heavy duties.106 Thus, the Irish state might be said to have gone to the extraordinary length of maintaining something of an appellation d’origine contrôlée system for export apparel. Unsurprisingly, such implied authenticity inhered in the use of natural textiles.

1958 plaid wool Jack Clarke suit label. The term ‘hand tailored’ is used on the label of the 1958 Jack Clarke suit to denote that the manufactured garment’s lining is hand-finished. Photo courtesy of UConn’s Costume and Textile Collection.

Since it is potentially confusing that both couturiers and designer-manufacturers used the government-regulated ‘handwoven’ label, the specifically Irish contexts of couture should be parsed briefly. Although Vogue named Connolly the ‘Vitamin C of the Erin-go-Couture movement’,107 it described her unusual modus operandi as alternating between couture proper for domestic clients and an older model of quality dressmaking for export that was an evolution of made-to-measure:

‘…she makes-to-order for the smart Irishwoman in the traditional way (deep-carpeted salon, hovering fitters); then, instead of selling models to America to be copied, she copies them in her own workroom and sends them there. Result: available originals, not copies, of her fresh-minded fashions in Irish fabrics.’ 108

Significantly, Women’s Wear Daily referred to Connolly as a ‘dressmaker’ in a 1953 cover showcasing her ‘lake green’ Kinsale cloak.109 By contrast, though Gilbert was less talented at self-promotion, her tastemaker client Lady Rosse regarded her as equal to the best in the London and Paris scenes.110 In addition, Mulcahy, who had received ‘a rigorous couture training’ with Madame de Gaulle’s dressmaker, received the artistic recognition of a National Museum of Ireland retrospective exhibition in 2007.111 Tellingly, Connolly never joined the Irish Haute Couture Group, founded in 1962 by Mulcahy, Gilbert, Ib Jorgensen, and Clodagh O’Kennedy.112

Irish fashion marketing case study: Jimmy Hourihan

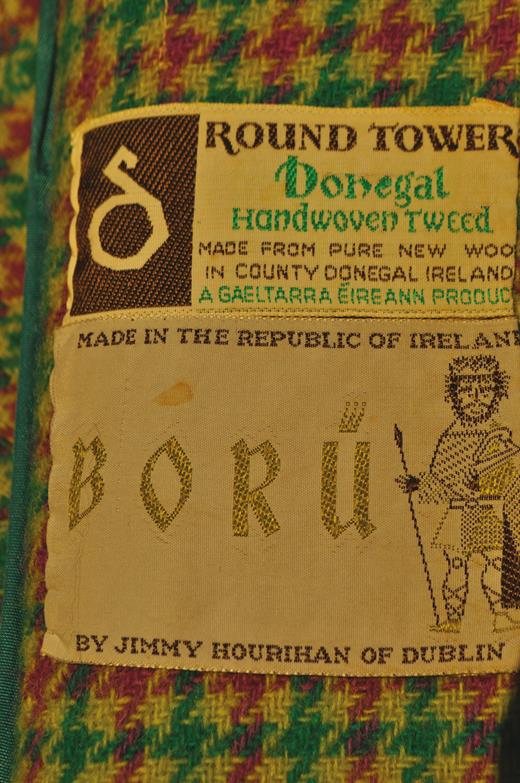

The need to be fashionable and to cater to the lucrative concept of heritage could lead to potentially conflicting messages. Take the labelling on a mid-1960s jacket by Clarke mentee Jimmy Hourihan [6], a designer-manufacturer of ready-to-wear (f. 1955, incorporated 1959). Jimmy Hourihan was, with Clarke, a pioneering Irish success in the new U.S. export market of those years. At his post-war zenith, Hourihan won an order for 1,200 tweed jackets from Saks on the back of a Córas Tráchtála-negotiated New Yorker feature, and his exports sales grew 300% between 1966 and 1967. (Hourihan is a rare survivor of that high point who still trades from his Dublin base, the location of our interview.113) The jacket boasts modish magenta, emerald and acid green colours and a fashionably boxy cut, and like the Clarke suit [4], its manufacture in Dublin is emphasized on the collar [7] and on the inside front label [8]. This repetition underlines the sartorial authority the Irish capital was then enjoying internationally: a mid-1950s Connolly green pleated linen couture dress is labelled ‘Sybil Connolly Dublin Classics.’114 In addition, the inside front fabric tag [8] sewn above Hourihan’s Aer Lingus menu graphic-inspired ‘Boru’ label115 conveyed the important message that the tweed was ‘handwoven’ in Donegal. It also credits ‘Gaeltarra Éireann’ (1957–79), a government project to promote industrialization in underdeveloped Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking) areas.116 The allied Gaeltacht Services Division of the Departments of Lands had standardized tweed production and encouraged the adaptation of machine-spun yarn in the post-Independence decades, even as marketing stressed the image of the homespun.117 By 1956, Gaeltarra Éireann was producing 600,000 yards of wool per annum, almost one third of which was being exported to America.118 (Such subsidy contrasted with the situation over the border in U.K.-constituent Northern Ireland, the long-established heartland of Irish linen, since the Belfast-based Irish Linen Guild was wholly industry-funded.119) Nevertheless, state policy regarding Gaeltachtaí reveals conflicts of economic and cultural policy and contradictory impulses to both undo and build upon colonial policy. Pace late Victorian cultural nationalists’ fetishization of the west, Gaeltachtaí were officially privileged as repositories for native language and culture by government cultural agencies. However, their boundaries followed the districts singled out as underdeveloped by the colonial-era Congested Districts Board, prompting industrialization endeavours such as Gaeltarra Éireann. Hourihan’s fabric label also utilizes Gaeltarra Éireann’s ‘Round Tower’ brand, a reference to a long-recognized signifier of inauthentic Irishness.120 This contrasts with the garment’s acknowledgement of the modernization project that was Gaeltarra Éireann and what WWD presented as the forward-thrusting nature of Hourihan Ltd.’s mid-1960s move to the Dublin Industrial Estate.121

Early 1960s Jimmy Hourihan handwoven Irish tweed jacket. Magenta, emerald and acid green Jimmy Hourihan handwoven Irish tweed jacket (circa early 1960s; part of a two-piece suit). Collection of the author.

Jimmy Hourihan jacket collar tag detail. The Hourihan jacket’s ‘Made in Dublin’ collar tag emphasizes the garment’s origin in a period in which Dublin enjoyed an international reputation in high fashion. Collection of the author.

Jimmy Hourihan jacket label detail. The Hourihan label re-emphasizes the firm’s Dublin location and also names and depicts Brian Boru, an eleventh-century and Dublin-associated king whose defeat of the Norse later made him a nationalist icon. The ‘Gaeltarra Éireann’ detail on the fabric tag refers to an Irish government marketing project for crafts from Irish (Gaelic)-speaking districts such as Donegal, which was set up in 1957.

The post-1960s decline of Irish fashion

Aran jumper knitting patterns circulated in Ireland from the 1960s on, but the style’s modishness in America allowed it to be read as both ‘modern’ and ersatz.122 Since a modernizing economy and society gained success by selling Ireland as ‘traditional’, mid-century fashion marketing arguably spearheaded the recent ‘easy, globally-digestible’ ‘Irishness’ business.123 Indeed, by 1959, the Irish Times was deprecating domestic couture’s continued reliance on ‘ancient Irish manuscripts and old, old legends…covering a multitude of anachronisms […].’124 The short-term gain of exploiting an image of Ireland as pre-modern arguably contributed to a decline in the cachet of Irish clothing in the long term. Even by 1960, the value of Irish woollen exports to the US was less than 40% of its 1957 peak of $1 million.125 A 2015 Vogue piece on ‘Jackie Kennedy’s Favorite Irish Designer’ (Connolly) suggested that ‘Fashion doesn’t top the list of things that Ireland…is known for—linen and lace, moss-topped cottages, and talents like James Joyce, Yeats, and Maud Gonne’.126 This betrayed—on the part of the industry’s publication of record—an absolute forgetting of the fact that for one twentieth-century moment, Irish ‘linen and lace’ was the fashion! The ‘Irish look’ became unfashionable as the 1960s penchant for synthetic and informal clothing increased and as an improved Irish economy led to textile outworker wage-hikes and thus higher prices. By 1973, a survey revealed that tourists to Ireland found Aran jumpers ‘bulky and unfashionable’.127 A further signpost to the future of both Irish and international fashion trends was that global ‘fast fashion’ player Primark opened its first store in the world under the name ‘Penneys’ in Dublin in 1969. In addition, Hourihan suggests that the post-1970s decline of the North American department store sector through which Córas Tráchtála had consolidated the success of ready-to-wear exports severely reduced the market for such goods. By Huston’s 1969 Vogue spread, Ireland was still being used as a backdrop for ‘country clothes’, but most labels in that shoot were American. This signposted developments after the post-war highpoint, when in international fashion parlance, ‘Irish’ becomes a free-floating signifier of the use of natural or heritage fabrics for garments or accessories that might be from anywhere.128 The globalization of the Irish economy and its output strategized by 1950s governments materialized, but it ultimately dissolved any meaningful use of the term ‘Irish’ in the high fashion context.129

If you have any comments to make in relation to this article, please go to the journal website on http://jdh.oxfordjournals.org and access this article. There is a facility on the site for sending e-mail responses to the editorial board and other readers.

Mary Burke, Associate Professor of English at the University of Connecticut, directs UConn’s Irish Literature Concentration. She is author of ‘Tinkers’: Synge and the Cultural History of the Irish Traveller (Oxford), and has articles forthcoming in James Joyce Quarterly and the American Journal of Irish Studies. A former NEH Keough-Naughton Fellow at University of Notre Dame and Boston College-Ireland Visiting Research Fellow, she chairs the MLA Irish Forum Executive Committee and is a former NEACIS President. https://uconn.academia.edu/MBurke

Footnotes

My deep thanks to my astute and generous JDH readers. This began as a paper at the 2011 CAIS conference, Concordia University, and was developed for a keynote address at the 2015 Mid-Atlantic American Conference for Irish Studies, Kutztown University of Pennsylvania. My thanks to Jimmy Hourihan, Laura Crow and UConn’s Costume Collection, Matt Mroz, and UConn’s OVPR, Lisa Doherty, Adam Hanna, Linda King, and Sarah Churchill.

Stephanie Rains, ‘Home from Home’, in Irish Tourism: Image, Culture & Identity, ed. Michael Cronin and Barbara O’Connor (Clevedon: Channel View, 2003), 196–199.

Bord Fáilte ‘oversaw an increase from 30 to 120’ of such products by 1957. Eric Zuelow, Making Ireland Irish, (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse UP, 2009), 70; 115–116.

Despite being ‘a tradition’ ‘for centuries’, by 1952 native linen sold to tourists rather than Irish ‘housewives’. Caroline Mitchell, ‘Is Irish Linen Holding its Own in the Battle for Markets?’ Irish Times, 15 June 1953, 6.

John W. O’Hagan and Francis O’Toole, eds. The Economy of Ireland (London: Macmillan, 1995), 34–35.

For a discussion of such strategy, see Jean Baudrillard, The System of Objects (London and New York: Verso, 1996), 73.

‘Fair trade’ West of Ireland tweed was exported by crafts patroness Lady Aberdeen for use in late-Victorian London women’s fashion. Janice Helland, ‘“A Delightful Change of Fashion”: Fair Trade, Cottage Craft, and Tweed in Late Nineteenth-century Ireland’, Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, 36, no. 2 (2010): 39; Janice Helland, ‘“Caprices of Fashion”: Handmade Lace in Ireland 1883–1907’, Textile History, 39, no. 2 (2008): 200; founded in the 1890s to develop impoverished regions, the CGB encouraged the creation of lace, knitting, and crochet schools in the Irish west.

See Transactions of the Central Relief Committee of the Society of Friends during the Famine in Ireland, in 1846 and 1847 (Dublin: Hodges and Smith, 1852), 77–78.

Hilary O’Kelly, Cleo: Irish Clothes in a Wider World (Dublin: Associated Editions, 2014), 12; <https://www.magee1866.com/en/Our-Timeline/cc-15.aspx> accessed 22 June 2017.

Though ‘faithful’ to ‘native wool fabrics’, Irish couturier Néillí Mulcahy’s spring 1961 collection possessed the ‘styling, colour and cut…prevalent [in] fashion elsewhere.’ Mitchell, ‘Neilli Mulcahy in Tweedy Mood’, The Irish Times, 1 February 1961, 5.

Hilary O’Kelly, ‘Reconstructing Irishness: Dress in the Celtic Revival, 1880–1920’, in Chic Thrills, ed. J. Ash and E. Wilson (Berkeley: California UP, 1992), 77.

O’Kelly, ‘Reconstructing Irishness’, 77.

Mitchell, ‘Knitted Glamour’, Irish Times, 7 September 1960, 4.

Elizabeth McCrum, Fabric & Form: Irish Fashion since 1950 (Stroud, Glos and Belfast: Sutton Publishing and the Ulster Museum, 1996), 5–6.

Siún Carden, ‘Cable Crossings: The Aran Jumper as Myth and Merchandise’, Costume, 48, no. 2 (2014): 261.

Linda King, ‘(De)constructing the Tourist Gaze: Dutch Influences and Aer Lingus Tourism Posters, 1950–1960’, in Ireland: Design and Visual Culture: Negotiating Modernity, 1922–1992, ed. Linda King and Elaine Sisson (Cork: Cork UP, 2011), 174.

O’Kelly, Cleo, 49.

Mitchell, ‘Knitted Glamour’, op. cit., 4.

‘Fashion: Coming-out Party for the Irish Couture’, Vogue, 15 September 1953, 134–135.

Ernest Hauser, ‘Fashions by Sybil Connolly’, Saturday Evening Post, 16 November 1957, 58.

Bettina Ballard, In My Fashion (New York: McKay, 1960), 252.

Sybil Connolly, Irish Hands: The Tradition of Beautiful Crafts (New York: Harvest, 1994), v.

Ubiquitous in guidebook illustrations of Irish ‘colleens’, the Kinsale was a fossilized survival of the earlier general European fashion for full-length cloaks. McCrum, op. cit., 4–5.

See Linda King, ‘Modern Ireland in 100 Artworks: 1953—Life cover, by Sybil Connolly, Irish Times, 1 August 2015, 9.

‘Enterprise in Old Erin: The Irish Are Making a Stylish Entrance into the World of Fashion’, Life, 10 August 1953, 47; 50; Hauser, op. cit., 56.

Sybil Connolly (obituary), The Economist, 16 May 1998, 94; Zuelow, op. cit., 116–117.

Mitchell, ‘Celtic Twilight Glamour’, Irish Times, 23 December 1959, 4.

Myles na gCopaleen, ‘Half a Mo!’ Irish Times, 14 July, 1954, 4.

Robert O’Byrne, After a Fashion (Dublin: Town House, 2000), 34.

Mitchell, ‘These Pseudo-Georgians!’ Irish Times, 4 June 1958, 6.

Facing-page and same-page photo accompaniments to the article ‘People are Talking About…in Dublin’, Vogue, 15 March 1954, 123;122.

Myles na gCopaleen, op. cit., 4.

An account of the Edwardian fad for Tara brooch replicas suggesting a vague ‘ancient Ireland’ effaced its colonial and commodity-culture history. This eighth-century pennanular piece was, in fact, purportedly discovered on a beach during the Famine by a ‘poor woman’. By 1851, replicas were being sold by Dublin jeweller George Waterhouse, including two to Queen Victoria. This is ironic because the shoreline discovery was possibly fabricated to circumvent a law stipulating that precious objects disinterred from the ground were the monarch’s possession. Mary Colum, Life and the Dream (New York: Doubleday, 1947), 107; Niamh Whitfield, ‘The Finding of the Tara Brooch’, Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, vol. 104 (1974), 131; 121–122; 134

‘Tara Pin’ (photo and caption), Women’s Wear Daily, 20 March 1953, 35; ‘Thatched Caps in Accessories by Sybil Connolly’, Women’s Wear Daily, 22 January 1954, 5

V. Pope, ‘Irish Couturier Shows Collection’, New York Times, 5 May 1954, 34.

The aforementioned satirist mocked that Connolly’s discussion of Donegal was created by Fógra Fáilte (f. 1952), the precursor to Bord Fáilte. Myles na gCopaleen, op. cit., 4.

O’Byrne, op. cit., 31; 28.

See Maud Gonnne, ‘The Famine Queen’, United Irishman, 7 April 1900, 5.

‘Raymond Kenna Autumn Collection 1958,’ Creation, August 1958, 33; Mitchell, ‘Waterford Glass Inspires Sybil Connolly Collection’, Irish Times, 16 July 1955, 4.

‘Lough Gur’, Vogue, 15 August 1954, 136–139.

Celanese acetate advert, Vogue, 1 November 1955, 32.

Mid-range American designer Anne Fogarty (née Whitney) traded on the Irish surname she had acquired through marriage to promote a 1954 range as ‘Irish-inspired’. Fogarty advert, Vogue, 1 February 1954, 96.

See Mary C. Kelly, Ireland’s Great Famine in Irish-American History. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014.

‘From Hand-knitted Socks to Grace Kelly—The Evolution of the Aran Jumper’, thejournal.ie, 15 September 2015; A Gilbert gown commissioned by the Princess featured in the 2010 V&A exhibition, Grace Kelly: Style Icon; R. O’Byrne, op.cit., 40; ‘Great American Country Clothes That Take the Gypsy Road...Anywhere...Everywhere’, Vogue, 15 October 1969, 74–97; Anjelica Huston, A Story Lately Told (New York: Scribner, 2013), 197; 204–205; McCrum, op. cit., 35; 16..

Connolly, op. cit., v; <http://www.ica.ie/An-Grianán/Courses.982.1.aspx> accessed 16 May 2016.

‘John Cavanagh’ (obituary), Times, 3 April 2003, 35; ‘Spring Fashions’, Times, 5 February 1952, 7; ‘Miss K. Worsley’s Wedding Dress’, Times, 23 March 1961, 16.

‘Daring Digby’, Life, 2 February 1953, 75; Mitchell, ‘Digby Morton’s Advice to Irish Fashion Trade’, Irish Times, 16 May 1955, 6; ‘Autumn Suits in Many Styles’, Times, 27 July 1955, 10; ‘The London Line’, Vogue, 15 September 1955, 130.

‘Face to Face…’, Creation, April 1959, 66.

Charles I. Bevans, Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America 1776–1949, 11 vols (Washington: Department of State, 1972), vol. 9, 46.

Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin, Flowing Tides (New York: Oxford UP, 2016), 195.

U.S. Social Security Administration data reveals that although ‘Shannon’ was absent from the 1950s name table, during the following decade 33,855 girls received it <ssa.gov/oact/babynames/decades/> accessed 16 May 2016.

aerlingus.com;<http://corporate.aerlingus.com/mediacentre/75thanniversary> accessed 16 May 2016; ‘The Sky is No Limit’, Creation, June 1957, 55; Rains, op. cit., 199–203; Hauser, op. cit., 56; Connolly, op. cit., 144; Brian O’Connell, John Hunt (Dublin: O’Brien, 2013), 144–148; 206–207; ‘Face to Face…’, op. cit., 66; ‘Tweeds, Harps, Currachs Grace Horne’s Event’, WWD, 21 September 1965, 54; Hauser, op. cit., 58.

O’Byrne, op. cit., 36; 39; 42. See ‘Irish Folklore Gives Fresh Inspiration to Sybil Connolly’, WWD, 20 July 1953, 35. Peterson’s 1960s fashion business was called Anna Livia, a latinization of Dublin’s River Liffey used by Joyce.

Mark Bence-Jones, The Remarkable Irish (New York: McKay, 1966), 101.

‘People are Talking About…in Dublin’, Vogue, 15 March 1954, 122; 155.

Mitchell, ‘Two Irish Spring Collections’, Irish Times, 31 January 1955, 6.

See Luke Gibbons, The Quiet Man. Cork UP, Cork, 2002.

‘Irish Mills Consider American Needs’, WWD, 25 January 1956, 44.

Mairead Dunlevy, Dress in Ireland (Cork: Collins, 1999) 140; 141; 166.

Brenna Katz Clarke, The Emergence of the Irish Peasant Play at the Abbey Theatre (Ann Arbor: UMI, 1982), 57.

Hugo Arnold, Avoca Café Cookbook (Wicklow: Avoca Handweavers, 2000), 10.

‘The Avoca Story’, a plaque at Avoca Mills, Wicklow.

Connolly, op. cit., ix.

‘Planning a Trousseau,’ The Times, 13 July 1938, 11; Elizabeth Ewing, History of 20th Century Fashion (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999), 107; McCrum, op. cit. 20.

Robert O’Byrne, ‘Couture for a Countess’, Irish Arts Review Yearbook (1996): 163.

‘[Connolly’s] inspiration comes from Ireland’s soil—the raw, black hills; the green, lush, rolling country; the brownish bogs.’ Hauser, op. cit., 57. Irish wool colours were the ‘turf browns…lush greens…sky tints and misty grays of the Irish countryside...’ ‘Irish Mills…’, op. cit., 44.

A letter regarding President Obama’s state visit complained of the absence of Irish tweed, ‘with its striking colours, which reflect the heathers, the grasses, the reeds and…the bog’ on ‘male dignitaries’. Letter to the editor, Irish Times, 25 May 2011, 15.

O’Connell, op. cit., 207.

‘Enterprise in Old Erin’, op. cit., 45.

‘Princess Grace, Rainier Lunch with Kennedys’, New York Herald Tribune, 25 May 1961, 3; ‘Princess Grace Captures Dublin: Begins State Visit Wearing Emerald Green Dress’, [Baltimore] Sun, 11 June 1961, 3.

O’Byrne, After a Fashion, 35; ‘Enterprise in Old Erin’, op. cit., 44.

Sybil Connolly (obituary), op. cit., 94.

Helland, ‘“Caprices,”‘ op. cit., 193–194.

Committee on Industrial Organisation, Report on the Survey of the Woollen and Worsted Industry, Stationery Office, Dublin, 1965, 10.

Sile de Cléir, ‘Creativity in the Margins: Identity and Locality in Ireland’s Fashion Journey’, Fashion Theory, 15, no. 2 (2011): 203.

Martin Wallace, The Irish: How They Live and Work (Newton Abbott: David & Charles,1972), 123; Niamh Hardiman and Christopher Whelan, ‘Changing Values’, in Ireland and the Politics of Change, ed. William J. Crotty and David A. Schmitt (London: Longman, 1998), 67; in 1943, President de Valera spoke of Ireland as ‘the home of a people…satisfied with frugal comfort.’ Joseph J. Lee, Ireland 1912–1985 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1990), 334; Andy Bielenberg and Raymond Ryan, An Economic History of Ireland since Independence (New York: Routledge, 2012), 128

During her 1950s heyday, Connolly was a bona fide celebrity who once gave twenty-six interviews to the American press in one day. Hauser, op. cit., 56.

King, ‘Modern Ireland’, op. cit., 9.

The Report of the government’s Commission on Emigration (1948–1954) suggested that lack of opportunities and the patrilineal inheritance system led to Irishwomen’s emigration. Ciaran McCullagh, ‘A Tie that Binds: Family and Ideology in Ireland’, Economic and Social Review, 22, no. 3 (1991): 206.

Leo Dana and Robert B. Anderson, International Handbook of Research on Indigenous Entrepreneurship (Cheltenham: Elgar, 2007), 218.

The mid-century Vogue editor called Connolly a ‘milk-skinned Irish charmer’. Ballard, op. cit., 252.

Hauser, op. cit., 29.

Seanad Éireann [Irish Senate], Industrial Research and Standards (Amendment) Bill, 1953, Second Stage, 25 February 1954.

Gary Murphy, In Search of the Promised Land: The Politics of Post-War Ireland (Cork: Mercier, 2009), 47.

See Design in Ireland: Report of the Scandinavian Design Group in Ireland, Irish Export Board, 1961; Committee on Industrial Organisation, op. cit., 175.

Creation, October 1957, 19; 9.

‘Glamour at Dublin Airport,’ Creation, June 1958, 27–30.

‘Sibley’s “Enchanting Ireland” Event Raking in the Green’, WWD, 6 October 1967, 24; Personal interview with Jimmy Hourihan, 23 August, 2016.

‘International Fashions: Paris, London, Italian, Dublin, Spain, American’, Vogue, 15 March, 1954, 88; ‘People are Talking About…in Dublin’, Vogue, 15 March 1954, 122.

O’Byrne, op. cit., 35.

Vogue cover, 15 March, 1954, 1; ‘Irish Designers First to Display Styles Abroad’, New York Times, 12 January 1959, 32; Macy’s advertisement, New York Times, 25 September 1960, 11.

‘Dublin Letter’, WWD 18 February 1955, 4.

‘“Surprise” Elements Cited in European Opening Fashions’, Women’s Wear Daily, 14 August 1953, 5; Alexandra Palmer, Couture & Commerce: The Transatlantic Fashion Trade in the 1950s (Vancouver: UBC and the Royal Ontario Museum, 2001), 79.

Hourihan interview.

Anne Harris, ‘Let’s Do Lunch’, The Gloss, September 2015, 32.

‘Phila. Fashion Group Likes “Bawneen” Skirts in Dublin Showing’, WWD, 11 August 1952, 3.

This origin was subsequently forgotten, with Connolly soon called a ‘lone wolf…taking no part in Government…export schemes.’ M. Neale, ‘Ireland’, WWD, 11 April 1960, 1

Pope, op. cit., 34; Creation, November 1956, 31.

‘Spring Clothes in New Shades’, Times, 10 January 1955, 2.

Snow’s father was Peter White, head of the Irish Woolen Manufacturing and Export Company (f. 1887). Penelope Rowlands, A Dash of Daring: Carmel Snow and Her Life In Fashion, Art, and Letters (New York: Atria, New York, 2005), 5–7.

Diana Vreeland, D.V. (New York: Knopf, 1984), 88–89; 170; Huston, op. cit., 204.

Details courtesy of Prof. Laura Crow.

McCrum, op. cit., 32; O’Byrne, op. cit., 20; 48.

Hauser, op. cit., 29; O’Byrne, op. cit., 26.

McCrum, op. cit., 24.

‘People are Talking About…in Dublin’, Vogue, 15 March 1954, 122.

‘International Fashions: Paris, London, Italian, Dublin, Spain, American’, Vogue, 15 March, 1954, 88.

‘Dublin Dressmaker’s Version of Traditional Irish Cloak,’ WWD, 10 March 1953, 1.

O’Byrne, op. cit., 12.

Deirdre McQuillan, ‘Elder Statement: Retrospective Exhibition of Neilli Mulcahy Designs Opens’, Irish Times, 18 October 2007, 10.

O’Byrne, op. cit., 40.

Hourihan interview; ‘Firm’s Export Sales Up 300% Compared With 1966’, WWD, 19 September 1967, 24; the firm still produces explicitly ‘Irish’ clothing, though it is no longer manufactured in Ireland. See <http://www.jimmyhourihan.com> accessed 16 May 2016.

Claire Wilcox and Valerie D. Mendes, Modern Fashion in Detail (New York:Overlook, 1991), 16.

Hourihan interview.

Dana and Anderson, op. cit., 218.

McCrum, op. cit., 3; Committee on Industrial Organisation, op. cit., 10.

‘Irish Mills…’, op. cit., 44.

Email correspondence from <info@Irishlinen.co.uk>, 20 June 2017.

See its use as tourist trap in George Bernard Shaw, John Bull’s Other Island (1904).

‘European RTW: The Irish: Jimmy Hourihan’, WWD, 1 May 1967, 26.

The 1966 Easter Rising fiftieth-anniversary celebration included a nationally-broadcast pageant in which narrators were attired in ‘Aran ganseys’ to suggest ‘the Ireland of to-day.’ Bryan MacMahon, Seachtar Fear, Seacht Lá, unpublished script, 1966, 2; A dramatized memoir of growing up German-Irish in 1950s Dublin records that the lederhosen and Arans of the child concerned reinforced his outsider status. Hugo Hamilton, The Speckled People (London: Bloomsbury, 2011), 16–17.

Debbie Ging, ‘Screening the Green’, in Reinventing Ireland ed. Peadar Kirby, Luke Gibbons and Michael Cronin (London: Pluto, 2002), 186.

Mitchell, ‘Celtic Twilight Glamour’, op. cit., 4.

‘Irish Woolen Shipments to U.S. Total $392,000’, WWD, 12 September 1960, 15.

Laird Borrelli-Persson, ‘How Jackie Kennedy’s Favorite Irish Designer Paved the Way for a Generation’, 17 March 2015, vogue.com; <http://www.vogue.com/12638904/sybil-connolly-jackie-kennedy-fashion-designer?curator=FashionREDEF> accessed 7 January 2016.

McCrum, op. cit., 47–48; O’Byrne, op. cit., 32; Zuelow, op. cit., 99.

A 2006 ‘Ireland’-themed advertorial featured ‘rustic charm’ apparel and accessories in wool and leather by American and British labels J. Crew, Vince, Coach and Alexander McQueen. M. Melling Burke, ‘Index: Checklist: Ireland’, Vogue, October 2006, 425

Today, items in the international fashion idiom by Ireland-born designers such as J.W. Anderson, Orla Kiely, or Simone Rocha never carry recognizably ‘Irish’ signifiers.