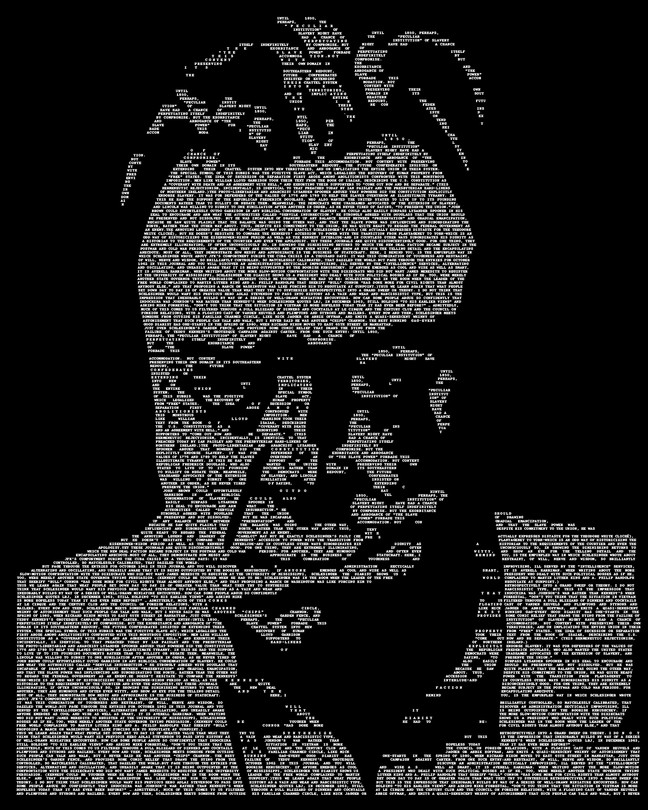

Arguably the Best of Christopher Hitchens

Celebrating the writer and Atlantic columnist on the tenth anniversary of his death

Christopher Hitchens died on December 15, 2011, 10 years ago today. He had been a columnist for The Atlantic for more than a decade, writing exclusively about books. (His reporting and other essays appeared in Vanity Fair.) Books being what they are, the Atlantic column gave Hitchens the freedom to write, in effect, about anything, and his range was wide: from Orwell and Trotsky to Lolita and Jeeves, from Hilary Mantel and Gertrude Bell to Mahatma Gandhi and Rosa Luxemburg.

When the British-born Hitchens embarked on the process of becoming an American citizen (a process he completed in 2007), he wrote about that in The Atlantic too, describing how a new national identity had stolen over him: “I had just completed work on a short biography of another president, Thomas Jefferson, and had found myself referring in the closing passages to ‘our’ republic and ‘our’ Constitution”—references he wasn’t aware of until reviewing the proofs. He had come to understand, he went on, that the American Revolution “is the only revolution that still resonates.”

Many of his Atlantic essays are collected in the book Arguably, published the year of his death. All of them are available at TheAtlantic.com. Herewith, a brief sampling.

— Cullen Murphy

THE MEDALS OF HIS DEFEATS

From a review of Churchill: A Biography, by Roy Jenkins.

It is truth, in the old saying, that is “the daughter of time,” and the lapse of half a century has not left us many of our illusions. Churchill tried and failed to preserve one empire. He failed to preserve his own empire, but succeeded in aggrandizing two much larger ones. He seems to have used crisis after crisis as an excuse to extend his own power. His petulant refusal to relinquish the leadership was the despair of postwar British Conservatives; in my opinion this refusal had to do with his yearning to accomplish something that “history” had so far denied him—the winning of a democratic election. His declining years in retirement were a protracted, distended humiliation of celebrity-seeking and gross overindulgence …

I can think such thoughts, and even adduce evidence for them, and feel all the cargo in my hold slowly turning over until there is no weight or balance left in the once sturdy old vessel. Stephen Jay Gould, reviewing the evidence of the fossil record in the Burgess Shale, offered the dizzying conclusion that if the “tape” of evolution could be rewound and run again, it would not “come out” the same way. I am quite sure that he is correct in this. But history really begins where evolution ends, and where we gain at least a modicum of control over our own narrative. I find that I cannot rerun the tape of 1940, for example, and make it come out, or wish it to come out, any other way. This is for one purely subjective reason: I don’t care about the loss of the British Empire, and feel that the United States did Britain—but not itself—a large favor by helping to dispossess the British of their colonies. But alone among his contemporaries, Churchill did not denounce the Nazi empire merely as a threat, actual or potential, to the British one. Nor did he speak of it as a depraved but possibly useful ally. He excoriated it as a wicked and nihilistic thing. That appears facile now, but was exceedingly uncommon then. In what was perhaps his best ever speech, delivered to the Commons five days after the Munich agreement, on October 5, 1938, Churchill gave voice to the idea that even a “peace-loving” coexistence with Hitler had something rotten about it. “What I find unendurable is the sense of our country falling into the power, into the orbit and influence of Nazi Germany, and of our existence becoming dependent upon their good will or pleasure.” Those who write mournfully today about the loss of the British Empire must perforce admit that the Tory majority of 1938 proposed to preserve that empire on just those terms. Some saving intuition prompted Churchill to recognize, and to name out loud, the pornographic and catastrophically destructive nature of the foe. Only this redeeming x factor justifies all the rest—the paradoxes and inconsistencies, to be sure, and even the hypocrisy.

AMERICAN RADICAL

From a review of The Singular Mark Twain, by Fred Kaplan.

There are four rules governing literary art in the domain of biography—some say five. In The Singular Mark Twain, Fred Kaplan violates all five of them. These five require:

1) That a biography shall cause us to wish we had known its subject in person, and inspire in us a desire to improve on such vicarious acquaintance as we possess. The Singular Mark Twain arouses in the reader an urgently fugitive instinct, as at the approach of an unpolished yet tenacious raconteur.

2) That the elements of biography make a distinction between the essential and the inessential, winnowing the quotidian and burnishing those moments of glory and elevation that place a human life in the first rank. The Singular Mark Twain puts all events and conversations on the same footing, and fails to enforce any distinction between wood and trees.

3) That a biographer furnish something by way of context, so that the place of the subject within history and society is illuminated, and his progress through life made intelligible by reference to his times. This condition is by no means met in The Singular Mark Twain.

4) That the private person be allowed to appear in all his idiosyncrasy, and not as a mere reflection of the correspondence or reminiscences of others, or as a subjective projection of the mind of the biographer. But this rule is flung down and danced upon in The Singular Mark Twain.

5) That a biographer have some conception of his subject, which he wishes to advance or defend against prevailing or even erroneous interpretations. This detail, too, has been overlooked in The Singular Mark Twain.

As can readily be seen from this attempt on my part at a pastiche of Twain’s hatchet-wielding arraignment of James Fenimore Cooper (and of Cooper’s anti-masterpiece The Deerslayer), the work of Samuel Langhorne Clemens is in the proper sense inimitable. But it owes this quality to certain irrepressible elements—many of them quite noir—in the makeup of the man himself …

Ernest Hemingway’s much cited truism—to the effect that Huckleberry Finn hadn’t been transcended by any subsequent American writer—understated, if anything, the extent to which Twain was not just a founding author but a founding American. Until his appearance, even writers as adventurous as Hawthorne and Melville would have been gratified to receive the praise of a comparison to Walter Scott. (A boat named the Walter Scott is sunk with some ignominy in Chapter 13 of Huckleberry Finn.) Twain originated in the riverine, slaveholding heartland; compromised almost as much as Missouri itself when it came to the Civil War; headed out to California (“the Lincoln of our literature” made a name in the state that Lincoln always hoped to see and never did); and conquered the eastern seaboard in his own sweet time. But though he had an unimpeachable claim to be from native ground, there was nothing provincial or crabbed about his declaration of independence for American letters. (His evisceration of Cooper can be read as an assault on any form of pseudo-native authenticity.) More than most of his countrymen, he voyaged around the world and pitted himself against non-American authors of equivalent contemporary weight.

THE MAN WHO ENDED SLAVERY

From a review of John Brown, Abolitionist, by David S. Reynolds.

Until 1850, perhaps, the “peculiar institution” of slavery might have had a chance of perpetuating itself indefinitely by compromise. But the exorbitance and arrogance of “the slave power” forbade this accommodation. Not content with preserving their own domain in its southeastern redoubt, the future Confederates insisted on extending their chattel system into new territories, and on implicating the entire Union in their system. The special symbol of this hubris was the Fugitive Slave Act, which legalized the recovery of human property from “free” states. The idea of secession or separation first arose among abolitionists confronted with this monstrous imposition. Men like William Lloyd Garrison took their text from the Book of Isaiah, describing the U.S. Constitution as a “covenant with death and an agreement with hell,” and exhorting their supporters to “come out now and be separate.” (This hermeneutic rejectionism, incidentally, is identical to that preached today by Ian Paisley and the Presbyterian hard-liners of Northern Ireland.)

The proto-libertarian and anarchist Lysander Spooner argued that nowhere did the Constitution explicitly endorse slavery. It was for defenders of the values of 1776 and 1789 to help the slaves overthrow an illegitimate tyranny. In this he had the support of the Republican Frederick Douglass, who also wanted the United States to live up to its founding documents rather than to nullify or negate them. Meanwhile, the Democrats were unashamed advocates of the extension of slavery, and Lincoln was willing to submit to one humiliation after another in order, as he never tired of saying, “to preserve the Union.”

John Brown could effortlessly outdo Garrison in any biblical condemnation of slavery. He could also easily surpass Lysander Spooner in his zeal to encourage and arm what the authorities called “servile insurrection.” He strongly agreed with Douglass that the Union should be preserved and not dissolved. But he was incapable of drawing up any balance sheet between “preservation” and gradual emancipation, because he saw quite plainly that the balance was going the other way, and that the slave power was influencing and subordinating the North, rather than the other way about. Thus, despite his commitment to the Union, he was quite ready to regard the federal government as an enemy.

THE COURTIER

From a review of Journals: 1952–2000, by Arthur M. Schlesinger.

The annoying legend and imagery of “Camelot” may not be exactly Schlesinger’s fault (he actually expresses distaste for the Theodore White cliché), but he doesn’t hesitate to compare the Kennedys’ accession to power with the transition from Plantagenet to York—which is an odd way of historicizing the Eisenhower-Nixon period as well as the Kennedy interlude—and in countless other ways subordinates his dignity as a historian to the requirements of the courtier and even the apologist.

Yet these journals are quite disconcertingly good. For one thing, they are extremely illuminating, if often unconsciously so, in showing the diminishing returns to which the New Deal faction became subject in the postwar and Cold War periods. For another, they are humorous and often even witty, and show an eye for the telling detail and the encapsulating anecdote.

Most of all, they demonstrate how messy and approximate is the business of statecraft. Here, I remind you, is the empurpled way in which Schlesinger wrote about JFK’s comportment during the Cuba crisis in A Thousand Days:

It was this combination of toughness and restraint, of will, nerve and wisdom, so brilliantly controlled, so matchlessly calibrated, that dazzled the world.

But page through the entries for October 1962 in this journal and you will discover an administration hectically improvising, ill served by the “intelligence” services, alternating and oscillating, and uneasily aware that it is being outpointed by the boorish Khrushchev. If anyone emerges as cool and wise as well as smart, it is Averell Harriman. When writing about the more slow-motion confrontation with the Dixiecrats who did not want James Meredith to register at the University of Mississippi, Schlesinger the diarist shows us a president who dealt with such political bosses as if he, too, were merely another state governor trying persuasion. (Kennedy could be tougher when he had to be: Schlesinger was in the room when the Leader of the Free World complained to Martin Luther King and A. Philip Randolph that Sheriff “Bull” Connor “has done more for civil rights than almost anybody else,” and that proposing a March on Washington was like forcing him to negotiate at gunpoint.)

Thus we learn again that what people set down day to day is of greater value than what they try to synthesize retrospectively into a grand sweep or theory. I do not think that Schlesinger would want his previous hero Adlai Stevenson to pass into history as a vain and weak and narcissistic type, but this is the impression that inexorably builds by way of a series of well-drawn miniature encounters. How can some people argue so confidently that Indochina was Johnson’s war rather than Kennedy’s when Schlesinger quotes LBJ, in December 1963, still holding “to his earlier views” and asking Mike Forrestal, “Don’t you think that the situation in Vietnam is more hopeless today than it has ever been before?” …

Admittedly, much of this comes to us filtered through a dull blizzard of dinners and cocktails at Le Cirque and the Century Club and the Council on Foreign Relations, with a floating cast of vanden Heuvels and Plimptons and Styrons and Mailers. Every now and then, Schlesinger meets someone from outside his familiar charmed circle, like Mick Jagger or Abbie Hoffman, and emits a quasi-senescent whinny of astonishment that such people can talk and walk, but I never said he was another “Chips” Channon. The best running gag—every good diarist has one—starts in the spring of 1980, when Richard Nixon moves to East 65th Street in Manhattan, just over Schlesinger’s garden fence, and provides some comic relief that draws the sting from the failure of Teddy Kennedy’s grotesque campaign against Carter. From one such entry:

Very few [Nixon] sightings … though when I throw open the curtains in the morning, around 7 o’clock, a fire is usually blazing in his fireplace. Lest he get too much moral credit for rising so early it should be noted that the Nixons seem to dine around 6 o’clock, an hour or so before we start pre-prandial drinking, and the house is generally dark by 9. Not New York hours.

LINCOLN’S EMANCIPATION

From a review of Abraham Lincoln: A Life, by Michael Burlingame.

Lincoln’s bicentennial has permitted us to revisit and reconsider every facet of his story and personality, from the Bismarckian big-government colossus so disliked by the traditional right and the isolationists, to the “Great Emancipator” who used to figure on the posters of the American Communist Party, to the reluctant anti-slaver so plausibly caught in Gore Vidal’s finest novel. Absent from much of this consideration has been the unfashionable word destiny: the sense conveyed by Lincoln of a man who was somehow brought forth by the hour itself, as if his entire life had been but a preparation for that moment.

We cannot get this frisson from other great American presidents. Washington, Jefferson, Madison—these were all experienced members of the existing and indeed preexisting governing class. So was Roosevelt. However exaggerated or invented some parts of the Lincoln legend may be, it is nonetheless a fact that he came from the very loam and marrow of the new country, and that—unlike the other men I have mentioned—he cannot possibly be imagined as other than an American …

Several moments in the narrative—the bee-fighting preacher being one such—put me in mind of Mark Twain. The tall tales, the dry wit, the broad-gauge humor, the imminence of farce even in grave enterprises: Lincoln’s inglorious participation in the Black Hawk War has many points of similarity with Twain’s “Private History of a Campaign That Failed.” Lincoln was once invited to referee a cockfight where a bird refused combat. Its enraged owner, one Babb McNabb, flung the creature onto a woodpile, whereat it spread its feathers and crowed mightily. “Yes, you little cuss,” yelled McNabb, “you are great on dress parade, but you ain’t worth a damn in a fight.” Long afterward, confronted with the unmartial ditherings of General George B. McClellan, Lincoln would compare the chief of his army—and subsequent electoral challenger—to McNabb’s pusillanimous rooster.

Mark Twain and Frederick Douglass, too, were persons who could only have been original Americans, sprung from American ground. It is engaging and affecting to read of Lincoln’s lifelong troubles with spelling and pronunciation (he addressed himself to “Mr. Cheerman” in his famous Cooper Union Speech of 1860) and of his frequent appearance with as much as six inches of shin or arm protruding from his ill-made clothes: truly a Knight of the Sorrowful Countenance. Yet despite, or perhaps because of, the extreme harshness of his early life, he was innately opposed to any form of cruelty, and despite his lack of polish and refinement, he almost never stooped to crudity or vulgarity in political speech …

It was once said that the Civil War was the last of the old wars and the first of the new: cavalry and infantry charges gave way to cannon and railways, and sail gave way to steam. It is of great interest to read Lincoln’s meditations on the projected postwar expansion of the United States, with a strong emphasis on mining and manufacturing. He had completely shed the bucolic influence of his early career and was looking in the very last days of his life to renew industry and immigration. Before Gettysburg, people would say “the United States are …” After Gettysburg, they began to say “the United States is …” That they were able to employ the first three words at all was a tribute to the man who did more than anyone to make that hard transition himself, and then to secure it for others, and for posterity.

THE 2,000-YEAR-OLD PANIC

From a review of Gregor von Rezzori’s novel Memoirs of an Anti-Semite.

Anti-Semitism is an elusive and protean phenomenon, but it certainly involves the paradox whereby great power is attributed to the powerless. In the mind of the anti-Jewish paranoid, some shabby bearded figure in a distant shtetl is a putative member of a secret world government: hence the enduring fascination of The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. (Incidentally, it is entirely wrong to refer to this document of the Czarist secret police as “a forgery.” A forgery is a counterfeit of a true bill. The Protocols are a straightforward fabrication, based on medieval Christian fantasies about Judaism.)

Of course when Jews do achieve actual power, like the famous Rothschilds, they often become the targets of even more envy than other plutocrats. Political anti-Semitism in its more modern form often de-emphasized the supposed murder of Christ in favor of polemics against monopolies and cartels, leading the great German Marxist August Bebel to describe its propaganda as “the socialism of fools.” Peter Pulzer’s essential history of anti-Semitism in pre-1914 Germany and Austria, which shows the element of populist opportunism in the deployment of the Jew-baiting repertoire, is, among other things, a great illustration of that ironic observation. And then there is the notion of the Jews’ lack of rooted allegiance: their indifference to the wholesome loyalties of the rural, the hierarchical, and the traditional, and their concomitant attraction to modernity. Writing from the prewar Balkans in her Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, Rebecca West noticed this suspicion at work in old Serbia and wrote:

Now I understand another cause for anti-Semitism; many primitive peoples must receive their first intimation of the toxic quality of thought from Jews. They know only the fortifying idea of religion; they see in Jews the effect of the tormenting and disintegrating ideas of skepticism.

The best recent illustration of that point that I know comes from Jacobo Timerman, the Argentine Jewish newspaper editor who was kidnapped and tortured by the death-squad regime in his country in the late 1970s. In his luminous memoir, Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number, he analyzes the work of the neo-Nazi element that formed such an important part of the military/clerical dictatorship, and quotes one of the “diagnoses” that animated their ferocity:

“Argentina has three main enemies: Karl Marx, because he tried to destroy the Christian concept of society; Sigmund Freud, because he tried to destroy the Christian concept of the family; and Albert Einstein, because he tried to destroy the Christian concept of time and space.”

The three cosmopolitan surnames involved in this anti-Trinity, it was made perfectly clear to Timerman between thrusts of the electric cattle prod, were considered to be no coincidence. But notice that this is an anti-Semitism that is full of dread as well as of disgust and contempt. That is perhaps what distinguishes it from other forms of racism.

LITERARY COMPANION

From a review of Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1930s & 40s and Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1920s & 30s, by Edmund Wilson.

In a beautifully turned reminiscence of Alexander Woollcott published in 1943, and originally intended as a defense of that great critic against an ungenerous obituarist, Edmund Wilson managed to spin what he admitted was a slight acquaintance into a charming portrait of a man and of a moment—the moment being the time when both men’s parents were connected with a Fourierist socialist community in Red Bank, New Jersey. Recollections of Woollcott the man of the theater, intercut with reflections on the arcana of the American left, combine to make a fine profile and a nice period piece: journalism at its best. What caught and held me, though, was an episode in the 1930s, when Wilson, fresh from reporting on the labor front for The New Republic, was invited to call on Woollcott at Sutton Place:

As soon as I entered the room, he cried out, without any other greeting: “You’ve gotten very fat!” It was his way of disarming, I thought, any horror I might have felt at his own pudding-like rotundity, which had trebled since I had seen him last.

This, and other aspects of the evening, make clear that Wilson understood why Woollcott’s personality didn’t appeal to everybody. But the preemptive strike on the question of girth also made me realize that there must have been a time when Edmund Wilson was thin.

This absolutely negated the picture that my mind’s eye had been conditioned to summon. Wilson’s prose, if not precisely rotund, was astonishingly solid. One cannot turn the pages of this heavy and handsome set, produced by the Library of America, without a sense of his mass and weight and gravitas. He was the sort of man who, as people used to say, “got up” a subject. The modern and vulgar way of phrasing this is to say that so-and-so reads a book “so you don’t have to.” Wilson, though, presumed a certain amount of knowledge in his readers, kept them well-supplied with allusions and cross-references, and undertook to help them fill in blanks in their education. An autodidact himself, he seems to have hoped to be the cause of autodidacticism in others …

It is not easy to imagine Mr. Wilson (he almost invariably alluded to other authors as “Mr.,” “Mrs.,” or “Miss”) sending in his annual recommendation for the summer “beach bag,” let alone responding to the even more rebarbative notion that people should be more likely to buy and enjoy books at Christmas. His famous preprinted postcard, which he sent out to supplicants of all kinds, showed him massively indifferent to the petty seductions of literary celebrity:

Mr. Edmund Wilson regrets that it is impossible for him to: Read manuscripts, write articles or books to order, write forewords or introductions, make statements for publicity purposes, do any kind of editorial work, judge literary contests, give interviews, take part in writers’ conferences, answer questionnaires, contribute to or take part in symposiums or “panels” of any kind, contribute manuscripts for sales, donate copies of his books to libraries, autograph works for strangers, allow his name to be used on letterheads, supply personal information about himself, or supply opinions on literary or other subjects.

But if this gives the impression of a sort of Jamesian loftiness, then the idea is counteracted by Wilson’s decision to engage with popular fiction. His contempt for the slovenly and disgraceful habit of “reading” detective stories—especially the dismal pulp produced by Dorothy L. Sayers—was offset by an admiration for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle …

One test of un homme sérieux is that it is possible to learn from him even when one radically disagrees with him. Wilson seems to me to underestimate the importance of Kafka in an almost worrying way (worrying because it shows a want of sympathy with those who just knew about the coming totalitarianism), yet I confess I had never thought of Kafka as having been so much influenced by Flaubert. When writing about Ronald Firbank, Wilson seems almost elephantine in his mass. Often somewhat out of sympathy with the English school—and again sometimes for self-imposed political reasons—he was very early and acute in getting much of the point of Evelyn Waugh. He was rightly rather critical of Brideshead Revisited, and it makes me whimper when I see how closely he read the novel, and how coldly he isolated unpardonable sentences such as “Still the clouds gathered and did not break.” Nonetheless, he predicted a big success for the book and, in discussing it and its successor The Loved One, managed to be both coolly secular and sympathetic, pointing out that Waugh was actually rather afraid of the consequences of his own Catholicism. An American critic might have chosen to resent the easy shots that Waugh took at Los Angeles and “Whispering Glades”; Wilson contented himself with indulgently pointing out that Waugh’s Church practiced a far more fantastic and ornamental denial of death than any Californian mortician.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.