Theatre and ritual are intimately connected. Indeed, theatre has its origins in ritual, and both have some of the same functions. They are both cathartic and transformational, but there are also some significant differences.

My ex-husband, who studied both theatre and the archaeology of ritual spaces, first pointed out to me some of the differences between theatre and ritual.

The fourth wall

In theatre, there is a “fourth wall“. The proscenium arch of the theatre is seen as a sort of transparent wall through which the audience observes the action of the play. It’s kind of weird, and sometimes even uncomfortable, when that fourth wall is breached. Examples of breaching the fourth wall include theatre-in-the-round, and asides to the audience.

In Wiccan ritual, the audience is the gods, the numinous, the divine. Since the ritual is done in a circle, the “doorway to the divine” is either visualized as the altar, or as being everywhere, since the divine realm is inter-permeable with ours. We generally do our rituals in secluded places where we are not likely to be disturbed; there’s no audience. Most religions have a requirement for their most sacred ritual to be members-only; having people who are observers and not participants is uncomfortable, for both the participants and the observers; this is especially true if participants are making themselves vulnerable in some way, either because they are skyclad or because they are being open about their feelings.

Sacred drama

As I mentioned in my previous post, Theatres are sacred, theatres were first formalized in Ancient Greece, but doubtless sacred drama is as old as ritual. It’s from the ancient polytheistic Greeks that we have written dramas, comedy, tragedy, and theatrical concepts like the chorus, catharsis and the deus ex machina.

Many anthropologists and archaeologists have speculated on the origins of ritual. It could lie in the practice of imitative magic; or it could lie in the human need for a story to make sense of our lives; or the need for rituals to negotiate changes in our lives, such as the transition from childhood to adulthood. Many cultures have rituals for these transitions (I have written about this extensively in my book, The Night Journey: Witchcraft as Transformation).

Sacred dramas are often performed as part of a ritual, but they are not the entirety of the ritual. The purpose of the sacred drama is often to achieve catharsis. Theatre often provides a secular form of catharsis.

Catharsis, Verfremdungseffekt, and transformation

A key feature of both theatre and ritual is catharsis. It’s a major part of the purpose of ritual, but perhaps more of a side-effect in theatre.

Catharsis (from Greek κάθαρσις, katharsis, meaning “purification” or “cleansing” or “clarification”) refers to the purification and purgation of emotions—particularly pity and fear—through art or any extreme change in emotion that results in renewal and restoration. It is a metaphor originally used by Aristotle in the Poetics, comparing the effects of tragedy on the mind of a spectator to the effect of catharsis on the body.

The purpose of catharsis can be transformational, or its purpose can be to reconcile the individual to the status quo, the consensus view of reality.

That’s why Brecht wanted his audiences to experience the Verfremdungseffekt instead of catharsis. He wanted them to look askance at the consensus view of reality, the status quo, and ask why it was like that.

Some rituals are intended to be transformational. Their purpose may be to accustom the participant to their new status in life (which is the case with rites of passage), or it may be to awaken them to new ways of looking at the world, in which case it is more like the Verfremdungseffekt (distancing effect), which provides a new perspective on life.

Deadly, Holy, Rough, Immediate

Peter Brook identifies four types of theatre. Deadly theatre is conventional, boring, lifeless, and obviously theatrical and artificial. Remember the Actors from Blackadder the Third? They were the epitome of deadly theatre.

Ritual can also be deadly when performed in a highly stylized and over-dramatic way.

Then there’s holy theatre, which is any theatre that dramatizes true emotions, rather than the empty shell of the outward expression of those emotions. Good ritual should also be holy theatre. The emotions invoked by holy theatre can be destructive as well as helpful; what makes it holy theatre is the genuineness of the emotions evoked.

Rough theatre is theatre that is not artificial, grand, lofty, or attempting to make any particular point. It’s street theatre, puppets, mummers’ plays, and other seasonal entertainments. Ritual can also be rough theatre; but beware of over-use of rhyme and rhythm, which all too often turns ritual into deadly theatre. Quite often the purpose of rough theatre (and rough ritual such as the Boy Bishop and the Bean King) was to let off steam and restore the status quo.

And finally, there’s immediate theatre, which is improvisational, extempore, emergent. The meaning and the story emerge during the performance; they are a collaboration between the actors and the audience. This can often happen in ritual, if people are comfortable with extemporizing. It can also happen with storytelling; a friend of mine who is a storyteller mentioned that on one occasion he told a story and the audience found it really sad; on another occasion, the audience laughed when he made a sound-effect, and this changed it to a comic performance of the story.

The purpose of theatre and ritual

Both ritual and theatre are intended to create meaning, to dramatize meaning, the body it forth in stories. Both can be cathartic, transformational, and either reinforce the status quo, or seek to challenge it.

Whilst the theatre was originally a sacred art, eventually a secular version of the theatre emerged. The origins of theatre lie in polytheist antiquity, where both comedies and tragedies were sacred, but Christianity initially had no use for sacred theatre (until the Mystery Plays emerged in the Middle Ages). After the Reformation, Christianity divorced itself even further from the theatre, and so the secular theatre was born.

The main difference between theatre and ritual lies in the intended audience and the structure of the performance.

The structure of a ritual

For a Wiccan ritual, we usually take some time to create a sacred space, and create the sense of the numinous. We sweep the space, cast a circle, and call the quarters; the purpose of this is to create the circle as a microcosmic representation of the cosmos.

In a theatre, the establishing action is to draw aside the curtains concealing the stage, revealing the world of the play. The fourth wall has been made transparent and we can now view the action.

At the end of a ritual, we have cakes and wine, a communal meal with the gods, and then we close down the sacred space.

In a theatre, the actors bow to the audience and receive their applause. Some of Shakespeare’s plays (and probably those of his contemporaries) end with a reminder that the play is now ended and normality is restored (and anything else you may be experiencing is therefore your own problem).

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.William Shakespeare

The Tempest, Act 4 Scene 1

The playwright confesses that everything you have just witnessed was an illusion created by the actors. It’s possible that this was a new thing, caused by the secularization of theatre.

That is not the intention of most rituals. Most rituals are intended to put their participants in touch with a deeper unseen reality (even if that is just your subconscious or your inner self, rather than the divine realms). That is why ritual begins with a process designed to put its participants in touch with their inner selves and with the cosmos, and ends with a process of gently closing down the perceptions that have been opened up, so that the participants can function effectively in the mundane spaces that they regularly inhabit. It’s all very well to cleanse the doors of perception and touch the infinite, but sometimes we actually do need to focus on the finite.

Participants in a ritual wear clothing that represents their inner self, their spiritual self; hopefully their most authentic self. Sometimes (such as for a rite of passage) they wear new clothing, to symbolize either a ritual state of purity, or an entrance into a new phase of life, or both. Actors in a play wear clothing designed to perpetuate the illusion that they are someone else.

Another purpose of ritual is to create community, and to share sacred meals, and sacred experiences, with other members of the religion. That’s one of the reasons why not being able to practice religion in groups during the lockdown is so painful: religion is a communal and embodied experience.

Theatre is also best experienced in person, in the theatre, with its magical atmosphere, but it is not designed to bring about group cohesion or group experiences. Unless the play is really cathartic, it is fairly rare to come away experiencing an identification, or a sense of belonging to a group, with other members of the audience. Each member of the audience has their own personal experience of the play.

Both theatre and ritual are extremely important ways of connecting with other humans, experiencing empathy, catharsis, storytelling, distancing effects, connection with community, and the magical art of acting. They are both similar and different; the main difference being the location of the fourth wall.

Vive la différence!

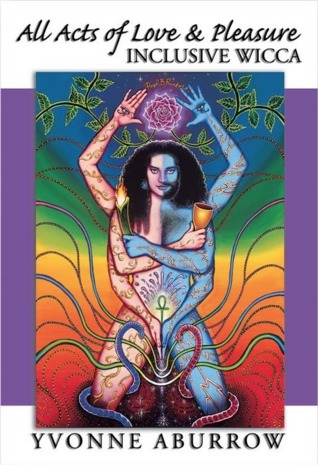

If you enjoyed this post, you might like my books.