A carbon capture proposal for a central Louisiana power plant has been titled “Project Diamond Vault” by its owner, Louisiana utility Cleco. The utility says the project will have “precious value” to the company, customers and state.

Yet less than six months after announcing the project to capture carbon from the plant’s emissions and store them underground near the plant, Cleco revealed in a recent filing to its state regulator the $900m carbon capture retrofit could reduce electricity produced for its customers by about 30%.

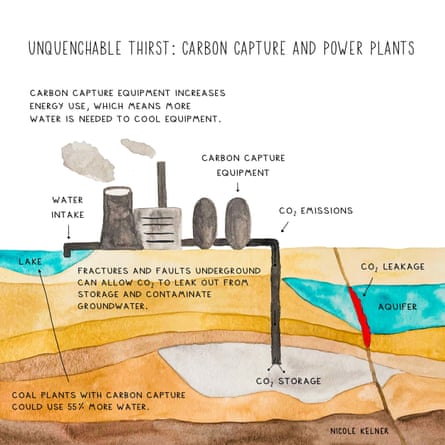

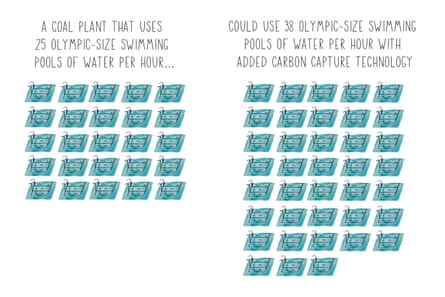

Cleco maintains it hasn’t committed to this path. But, if it decides to produce additional power necessary to run the carbon capture process, it could increase the plant’s water use by about 55%, according to studies of similar power plants.

The Louisiana project is not an outlier.

Operating enough carbon capture to keep the climate crisis in check would double humanity’s water use, according to University of California, Berkeley researchers. Regardless of the method being used – on a power plant or capturing carbon directly from the air – more power and more water will be needed.

The Cleco proposal provides an object lesson in how one solution can exacerbate another problem.

“These technologies to mitigate climate change have unintended environmental impacts, like water use and water scarcity,” said Lorenzo Rosa, a principal investigator at Carnegie Institution for Science at Stanford. Carbon capture and sequestration increases water withdrawals at power plants between 25% and 200%, according to an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report that cites Rosa’s work.

The same IPCC report says carbon capture could help reduce the fossil fuel pollution that is heating the planet’s climate and causing more extreme weather.

The power generation unit to which Cleco plans to add carbon capture technology – the Madison 3 unit – makes electricity by burning 70% petroleum coke, a byproduct of oil refining, and 30% coal. It’s been estimated that retrofitting a coal-fired power plant with carbon capture technology could increase that plant’s water use 55%. A similar increase could be expected for retrofitting a petcoke power plant, Rosa said.

Cleco, however, told Floodlight it can’t definitively say how much power and electricity the carbon capture process will use until initial designs and studies are complete in 2024. “Cleco is committed to research and engineering at the highest level and cannot speculate on the findings of the study,” the company said in an emailed response.

The proposed carbon capture technology for the plant chemically strips carbon from the exhaust of fossil fuel-burning facilities. Cleco expects that running the carbon capture equipment will use 200 megawatts of electricity, according to a recent Louisiana Public Service Commission filing. That’s about a third of the 641-megawatt power station’s current capacity.

The industry says retrofitting certain fossil fuel-burning power plants is cheaper than shutting down the facilities and building renewable energy. To offset the cost of the technology, companies can use the carbon to force more oil out of ageing oilfields.

Adding the technology to power plants is expensive. Wyoming, which produces 40% of the nation’s coal, passed a law requiring electric utilities to produce some of their power from coal-burning power plants with carbon capture. So far, that’s proved unfeasible as power companies have warned the technology would probably increase water use and could increase residential electricity bills by as much as $100 a month. A study by Energy Innovation: Policy and Technology found coal plants retrofitted with carbon capture technology were three times more expensive than wind power and twice as expensive as solar.

Despite the problems, the push for carbon capture in the state is moving ahead. Louisiana’s Gov. John Bel Edwards, a Democrat, praised the Cleco project, saying at the Project Diamond Vault announcement that it and similar projects to reduce energy climate pollution are critical for the state.

More than a dozen carbon capture projects have been proposed in Louisiana as lawmakers and industry leaders pitch carbon capture as a solution to the state’s industrial carbon emissions. Louisiana is one of the nation’s top emitters of carbon dioxide, and Project Diamond Vault is the only carbon capture proposal for a power plant in the state. The other proposals deal with other industrial processes or carbon storage.

Last year’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law allocated $12bn in federal funding toward carbon capture and storage technologies, and August’s Inflation Reduction Act creates tax breaks for power plants and industrial facilities that pursue carbon capture and storage (CCS). The federal support for the technology is critical: no industrial-scale power plant in the US currently uses CCS, largely because it is costly, according to the Congressional Research Service.

The need for additional water for carbon capture would strain drier regions of the country. But even in Louisiana, which gets more rain on average than any other of the 48 contiguous states, additional water use could be problematic. It doesn’t have a statewide water management plan and in some areas, groundwater is being sucked up faster than it can be replenished. Power generation is by far the biggest freshwater user.

“To assume this water is available is a mistake,” said Mark Davis, director of the Tulane Institute on Water Resources Law and Policy said of the water needed for CCS. “It’s a mistake that can be avoided.”

Cleco has three power generation units that pump up to a combined 700,000 gallons of water a minute from adjacent Lake Rodemacher to cool equipment, according to 2021 US Energy Information Administration data. In 2015, power generation accounted for about 98% of surface water withdrawals in Rapides Parish, where Cleco’s Rodemacher Power Station is located, according to the state’s most recent five-year water use report.

Water policy experts have raised concerns about Louisiana’s lack of a statewide management plan before, most recently when hydraulic fracturing for natural gas and oil became common in the state. The growth of hydraulic fracturing, which uses millions of gallons of water, in northwest Louisiana, prompted legislators to enact a voluntary surface water management program in 2010.

Earlier this year, Sen. Robert Mills, a north Louisiana Republican lawmaker, introduced a bill aimed at making the agreements mandatory, which would have forced companies to pay for the water they take from rivers and lakes. Oil and gas lobbyists blocked the proposal, Mills said.

“We’ve been giving away water for all this time,” Mills said. “The state’s constitution says you can’t give away something of value.”

The legislation died in committee, with no legislator moving to push it forward.

“We’ve got plenty of water today,” Mills said. “But what about tomorrow?”

This story also published in the Louisiana Illuminator and The Lens.

This reporting is supported by a grant from the Fund for Environmental Journalism.