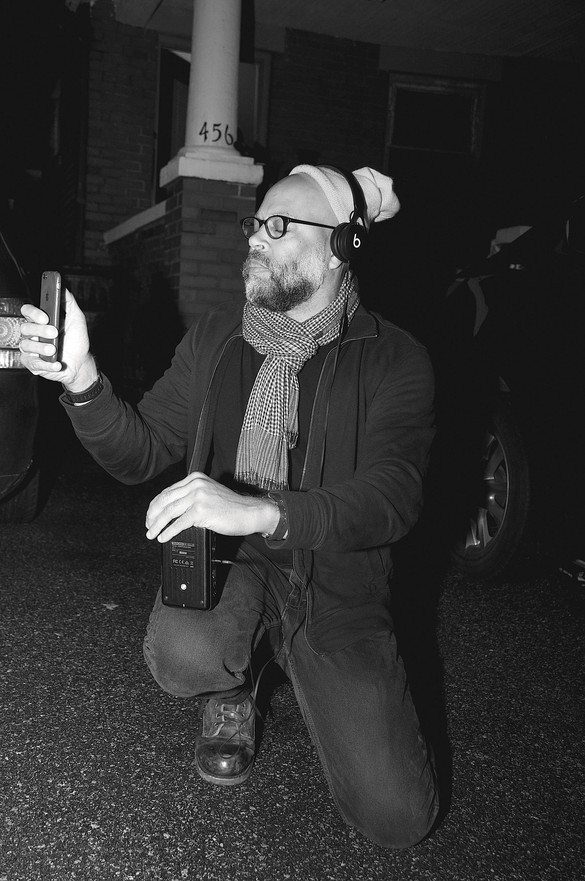

Carlos Valladares is a writer, critic, programmer, journalist, and video essayist from South Central Los Angeles, California. He studied film at Stanford University and began his PhD in History of Art and Film & Media Studies at Yale University in fall 2019. He has written for the San Francisco Chronicle, Film Comment, and the Criterion Collection. Photo: Jerry Schatzberg

Topography love: that’s the game of Kevin Jerome Everson, one of the premier cinematic visionaries of our time. Everson’s audiovisual work evades every label that could be used to pin it in place: experimental, avant-garde, Black, US cinema, found footage, twenty-first century, fantasy, nonnarrative, and, the most dreadful of all, “realism” and “documentary.” Everson demolishes staid notions of the natural and the real. To meet the challenges of perception and existence demanded by his cinema, the viewer must refuse the belief that they can ever “know” anything about the “reality” of his filmed Black subjects, their work, the lives they lead when the camera isn’t rolling or when the festivals have shut down. His films play seriously with the omnipresent yet invisible histories packed into signifiers like “body,” “Blackness,” “knowledge,” “time,” “process,” and “work.”

To date, Everson’s oeuvre consists of over two hundred films varying in length from one minute to eight hours. His camera focuses on a wide berth of predominantly African American subjects engaged in a variety of experiences, activities, and events. The films are primarily set across the US South and Midwest, in locations such as Everson’s hometown of Mansfield, Ohio. To demand clarity from these unruly movies is to deal a disservice to them. It is the task of the 2021 filmgoer to meet Everson’s subjects and work toward them, not the other self-serving way around.

Watching Everson’s films, one gets the sense that he has shot miles of footage only to select the shots that show the least and tell even less. Everson denies you a zone of privileged access into his subjects, the modus operandi of most conventional “explain-and-show-it-like-it-is” documentaries. His unique harmonization of crisp, suspended flows of time, Black being, slippery reality values, and a poetry sculpted from the quotidian dwells in a zone that Kobena Mercer has called the “in-between,” a diasporic sashaying and unmooredness that doesn’t stick to the frozen high values of the midcentury modernists, an “in-between” that assumes all art as political even if not at the surface.1 Here, the “in-between” refers to Everson’s sidestepping of various presumptions typically grafted onto Black artists like him and others in the United States. This “in-between” destroys notions of a strictly universalist consideration of the cinema—i.e., a white, ahistorical, hegemonic notion of what constitutes humanity. It also frees the Black artist to use the language of abstraction, of nonnarrative, of poetry, to move away from trying to find “verification” or a limited reality-value through private, intimate details in the Black artist’s life. Everson swirls his practice within and about Blackness, yet never reaches a fully communicated, totalized notion of it. I take as my guiding point, with regards to the latter, what Tom Meisenhelder writes in regards to notions of “whiteness” and “Africanness”:

It is by defining the African other as a “black body” that the European identified itself as a “white soul.” Using the ideas of Lacan (1977) it is possible to see that European cultural identity was formed in part via the confused introjection of the African other. . . . The precolonial representation of the African other provided the general rules of discourse that have informed how Europeans think, talk, and act with reference to Africans.2

Everson rejects being defined in the exclusive terms of the European-derived “Black body”; in every film venture, the Black subjects he films become reified in the name of the act of “creative interpretation,” to use Michael B. Gillespie’s words in his seminal Film Blackness: American Cinema and the Idea of Black Film (2016).3 Everson reverses “the uneven critical burden whereby the fundamental value of a black film is exclusively measured by a consensual truth of the film’s capacity to wholly account for the lived experience or social life of race.”4

In Cinnamon (2006), we see the in-between in action. Mortgage-loan-officer Erin (played by Erin Stewart, actress and graduate of the Drama School at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, where Everson is a professor of art) is stifling in her white-collar office job, where she’s in perpetual search for a ballpoint pen to log down tiresome bureaucratic business. She can’t wait for the weekend, when she can race her dragster on dirt roads, guided by the mechanic John Bowles, a bracket racer for decades. Rejecting a likable Ford v Ferrari plot, and the easy-to-parse social dynamics of loyalty and professionalism that pervade every buddy-buddy film about a sport, Everson is most intrigued by the friction and drag of tires on dirt, the nitty-gritty that even Howard Hawks (a master of action and gesture, as seen in his 1932 racing flick The Crowd Roars) never had time to show: the sputtering motors, the whirling engines, the air thick with dust and gas. Any personal business is neatly played down, and when it does come up, the personal is clouded by elusive memory: an enigmatic teddy bear, for instance, belly stitched with a pink heart bearing the words “i love you,” adorning the bed of Ashley Bowles, John’s daughter and a Black-girl drag racer in the making. John, in a eureka moment, says to himself, “That’s what drag racing is: consistency.” What’s being endorsed here is evenness of temperament, the need for the artist to wield their tool, whether car or camera, with restraint and a respect for the arduousness of process. A lot of waiting fills up the spaces of Everson’s movies, in conspiratorial league with the tough, low-to-the-ground, tedium-forged miracles of Chantal Akerman or Andy Warhol. In Everson’s work, waiting for the show to begin, a harbinger for Something Else, becomes the main event.

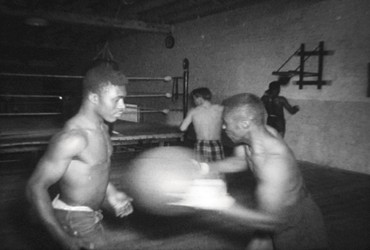

Everson sketches out vast formal worlds in ten minutes or less. Witness Old Cat (2009), Undefeated (2008), and Ring (2008), three short films that recall the histories of cinematic representation in order to trouble the photograph’s claim to unfettered reality. I turn to a description of Old Cat by Ed Halter in a 2010 issue of Artforum: “Old Cat . . . consists of an unbroken roll of silent black-and-white 16 mm, shot by Everson in a small boat navigating what seems to be a broad river. One man pilots the boat from a perch at the fore; another lies port side with his leg in a splint, crutch under his right arm. What seems like a single-take slice of life is in fact an instance of theater: the man’s injury is fabricated, inserted into the shot as a means of suggesting some unseen narrative.”5 With regard to Undefeated, I turn to an even shorter description by Everson himself: “Undefeated is about mobility and immobility, or just trying to stay warm.”6 The film features DeCarrio Antwan Couley (Everson’s son) shadowboxing to the rhythm of a hand-cranked Bolex.

Everson does not limit himself to a particular movement or national style; rather, he engages in a struggle with the entire cinematic apparatus, the labor concealed and the politics denied by the institution of viewing, watching, and listening.

To discuss both of these works, it strikes me to bring up the point Everson himself makes with regard to his cinematic affinities. He denies, for instance, the “obvious” route—the “constant” comparisons, in his view, between himself and the Black narrative filmmaker Charles Burnett, known for his 1978 masterpiece Killer of Sheep, set in a predominantly Black neighborhood in South Central Los Angeles. For Everson, a better comparison is with the films of “the Filipino experimental digital filmmakers Khavn de la Cruz, Lav Diaz, and John Torres.” As he said in 2013, “Lav Diaz makes these nine-hour narrative films; they’re so cool. Like if it takes twenty minutes for the oxen cart to come down the road, it takes twenty minutes for the oxen cart to come down the road. But there’s something that’s super fucking humane about that. It’s so visceral.”7 Like Diaz, whose films are notoriously “difficult” (because lengthy), Everson does not limit himself to a particular movement or national style; rather, he engages in a struggle with the entire cinematic apparatus, the labor concealed and the politics denied by the institution of viewing, watching, and listening. Surpassing what is considered the “norm” of the cinema experience, Diaz breaks the contract of pleasure, equated with instant understanding. Everson takes up a similar challenge.

It is crucial to tie Old Cat and Undefeated to the first filmmakers, the inventors of the cinematograph. The Lumière brothers are best known for their early films of the 1890s, shimmering one-shot “actualités” that feature white French citizens—working class, bourgeois, aristocrats—engaged in a variety of activities: a couple feed their baby, workers leave a factory, a gardener gets hosed by kids in a park, and so on. Undefeated lasts the exact length of time a Lumière actuality typically did: fifty seconds, an entire reel of film in 1896. And certain Everson films explicitly revisit the images of one of the Lumières’ most famous films, La sortie de l’usine Lumière à Lyon (Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory, 1895): 2013’s Workers Leaving the Job Site (Black construction workers punch out the clock for the day) and 2017’s Rams 23 Blue Bears 21 (spectators file out in single file at the conclusion of a football game and react to Everson’s camera). All of the above films make subtle nods to the Lumières in the intense focus on gesture and the bleed-through of presentational artifice and unrepresented “reality-caught-unawares.”

In Undefeated, a young Black man—Couley—bounces up and down in the cold, jabbing the air as if boxing. His car has broken down on the side of a freeway; its hood is up, and his companion (James Everson, the filmmaker’s father) inspects the engine as cars whoosh by. In none of the above films are the profilmic events integrated into a master narrative that indulges the audience’s craving for engagement or entertainment. If anything, what is filmed are shards presented as such, unintegrated. There’s a dialectic of symbolic movement: the stalled car as a counterpoint to the jabbing, always-on-his-toes Couley, “undefeated,” the spirit and labor of the boxing ring divested from its physical location . . . reappearing as the titular symbol on the side of some hushed-away highway. This dialectic is mirrored in the form of the film and in Everson’s larger project. He divests his filmed subjects from what’s perceived as their common purview—narrative, explanation, documentary—while still thoroughly investing himself in questions pertaining to theatricality, performance, and action. It is hard (and historically untenable) to return to the kind of pure automatism of the Lumières. It is hard due to the ingrained expectation of smooth narrative that the moving image has encouraged for the century-plus of cinema’s existence. All the same, Everson still poeticizes that luminescence, that primacy of raw seeing. His camera registers the bits that can’t be inscribed into a larger order: wind rippling through the boatman’s white shirt in Old Cat, the play of grays on his skin, the older blue-shirted man who hilariously returns back to the work site in Workers Leaving the Job Site.

Everson shows both what happens outside the work site and what happens within it. In his mammoth Park Lanes (2015) we get peeks into this inside, but only peeks. The setting: a day in the life (shot over a period of a week) of the sweating and business that go on inside a factory that constructs—of all things—bowling alley equipment. The duration: exactly eight hours. A film that works like an inverted Kino Eye (1924; what’s prized is long takes, not the cut-’em-up frenzy of Dziga Vertov’s montage), this 480-minute valorization of labor doubles as mystification, lasting as long as the average factory shift in the States and in total rejection of any “explanation” of how a gutter gets built. For seven hours, parts are manipulated, and Asian, white, and Black workers laugh at lunch breaks. Then, in the final hour, we see the completed lanes. It’s one of the most fabulous films of unfolding I’ve ever experienced.8

As it starts, it’s early morning. One Black worker whom we follow from beginning to end complains with a guffaw to her colleagues in the break room, “I thought today was Thursday. Looked at my phone and went: ‘Ohhh. It’s Wednesday.’” Tiredness and forced indefatigability are the first notes sounded for the day. Later, a Black woman who ties up her hair in braided buns manipulates a series of long metallic arm-things for a good half-hour. I have no clue what the hell this arm-thing is, or where it even ends up in the blueprint for the bowling lane. But it’s engrossing to watch her toil over her component with monk-like precision. As she plays with it, a radio plays softly in the background, so that, for eight hours, we hear the perfect soundtrack to 2010s late-capitalist life. Don’t want to work? Neither do we! At least there is pop to remind us that “Big Girls Don’t Cry,” that “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun,” that “Just Like a Prayer, I’m Gonna Take You There,” that in this country, “Sugar, We’re Goin’ Down, Down,” and that maybe some day we can say “We Found Love in a Hopeless Place” (not the club, but the break room). These are the same Top 40 radio hits that bored teens will hear at a bowling alley on a Saturday night once all this alienated labor has produced its perversely specific commodity.

Park Lanes also features an intervention in the cinematic Symbolic for the ages: a young Black man takes a black paint nozzle and—elegantly, without muss—sprays the black paint across a flow of white metallic sheets on a conveyor belt. In Footlight Parade, a Warner Bros. backstage musical from 1933 starring pearly-white guys and dolls, Jimmy Cagney walks down a city street and, in a sudden burst of insight, conjures a foolproof plan to lure viewers into his movie theaters. The subsequent shot-reverse shot revealing his plan is the most blatant existing admission of whitewashing within the racist studio system. The shot: “That’s it!” Cagney cries on a New York street as he sees something offscreen that sparks his aesthetic epiphany. “That’s what we need! Beautiful white bodies on the screen!” The reverse shot: Black kids laughing, playing, and showering in a broken fire hydrant. Flash forward to 2015, where the terms of the imagination have flipped: now, Black living (in Everson’s work) is taken as the base of Cagneyian action, the material and psychic and symbolic foundation on which notions of the state and the individual are rejiggered. The ground below us becomes as unstable and fluid yet omnipresent as the river in which two teens baptize their friend for the camera in The Island of St. Matthews (2013).

Everson toils within cinema, but he rails against the institution of visibility that gives it legibility.

Flooding is of central concern to this gorgeous film, set in Westport, a small community to the west of Columbus, Mississippi, the hometown of Everson’s parents. In 1973, Westport’s citizens were hit hard by the great flood of the Tombigbee River, and most folks lost everything: heirlooms, photos, homes. One of those who lost everything was Everson’s own aunt. So there’s a family connection, one that spills across the entirety of Everson’s films as various relatives play a host of personae. But St. Matthews quickly spirals beyond the familial into a knotty rumination on a host of daily sensations: water, its overflow, control and the lack of it, the beautiful stillness of surface, Black hands, delicacy, deliverance, survival, the casual, the coped with, the tyranny of visibility, ripples, starting and restarting, rebirth. Now, the flood survivors are impeccably dressed and bejeweled and coiffed. Presenting a version of themselves to the camera in their best Sunday church duds, they recall all the intimate details of the flood. Juanita Everson, Kevin’s aunt: “I was just married, and Roses and Sears Department Stores sold sheets and towels and clothes for 10, 25 cents each. And that was a wonderful thing, because a lot of people lost everything in their homes: they lost family pictures, heirlooms. And that’s the important thing, ’cause I’m a shopaholic, and I started then,” followed by a profound laugh, exemplary in its nonchalance. A woman next to Juanita: “It was awful. But we survived. And that’s about it.” Everson’s camera records historical events not as textbook as Kennedy’s assassination or Iran-Contra, but falling rather among those small microhistories that would barely make a dent in the footnotes of logy doctoral dissertations. These are the hyperlocalized events whose traces make themselves heard through long patches of communal silence, grainy floating voices that refuse to separate the remembered and the ongoing.

Everson toils within cinema—the medium of the visible par excellence, owing to those indexical traces of the moving, physical world that we quaintly assume is reality—but he rails against the institution of visibility that gives it legibility. He undoes the viewer, asking her to question her relationship to images that purposely refer to more than they can show. Thus the art of material existence emerges, in ways to which the viewer is unaccustomed, weaned, as she is, on the cotton candy–like entertainments of Hollywood or the stagnant seasons of Netflix. As Everson avoids this cliché of insightful art, the event dissolves into a series of pulses: illegible shop talk about diesel drag-car engines, the quality of rope used for calves in Black rodeos, lunch-hour predictions for how a season of NBA All-Star basketball will wind up.

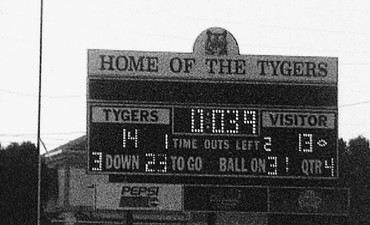

Hortense Spillers asks us, “What is this thing called ‘race’? Our deadliest abstraction? Our most nonmaterial actuality? Not fact, but our deadliest fiction that gives the lie to doubt about ghosts? In a word, ‘race’ haunts the air where women and men in social organization are most reasonable.”9 Race is the Lacanian Real haunting the air of Home (2008), which focuses on the final seconds of a football game at a predominantly African American high school. But the only shot in the film is a fixed, distant one trained on the scoreboard. No literal Black bodies are seen, but they’re sensed behind and beyond the camera, framing the reality of US easy living. (I write this as the Super Bowl is going on and America tries to forget racial capitalism for a few hours. How? By watching TV commercials in between the collisions of Black bodies.) In Home, the problematics raised by race are abstracted into the symbolic sphere of “Tygers/Visitor/3 down/23 [seconds] to go,” with the Pepsi logo underneath. We see “only” this, but we feel the spectacle, those crashes of bodies that are being neatly elided by the misleading signs of unquestioned reality. We sense the rah-rah in the stadium. We hear the voices of the crowd. But the scene has been fantastically pared down. Home is of a piece with Ring, where what’s accentuated is the balletic grace of the Black boxer (process), as opposed to what punches do to his face (destination). Only in the case of Home, no body is ever seen.

Everson’s work seeks out the something else that Spillers also seeks when she writes, “Currently, the cultural analysis offers no theory of the ‘everyday’ and appears to have no firm grasp of social subjects in relationship to it.”10 Such language, I think, can partly be found within the visual histories and works uncovered by Everson, even as he complicates one’s notion of what goes into an everyday. In Grand Finale (2015) we look at the backs of two boys’ heads as they look at a last volley of fireworks in the Detroit sky. The main event is the people gathered for the event. One of the boys is recording the fireworks, and observes them on his digital phone. This is not an unfiltered everyday; the daily is explicitly mediated through the lens of the camera. As Everson hones his eye in his most recent 2010s work (Park Lanes; Erie, 2010; and the 2017 masterpiece Tonsler Park), these notions of an everyday emptied of typicality—yet still, to some degree, a “watchable,” consumer- and audience-oriented everyday—have been pushed to the durational Diaz-Akerman extreme.

What we see in Tonsler Park is not the real, not what really goes on at an Election Day November 2016 polling station in Charlottesville, Virginia, several months before the infamous Unite the Right Rally in which a right-wing white supremacist intentionally rammed his car into a crowd of counter-protesters, killing one. That’s what the official record of history states, but not the Everson record. Though Tonsler Park is more honest than the intentionally misleading cable-news “explanations” of how Black people in the United States feel judging by how they vote, it’s also the day-to-day bereft of obvious context: the local candidates, the private jokes told between neighbors and friends in the voting queue. Thus, next to Roberto Rossellini’s Socrates (1971), Everson crafts the least sensational, nongiving, and most geometrical democracy movie in existence. You would expect him to fly off in a million directions once the voting day commences. Instead, a thrilling alienation overcomes the viewer as Everson sticks to one worker for nearly ten minutes, observing her every move, then panning briefly to her neighbor, who’s obscured by the backs of voters, before panning back to her, diligently registering each ballot and handing them out to prospective voters. It is up to the viewer to fill in the symbolic gaps. The boredom and tedium of the electoral process, what’s usually not shown or dwelled on—it’s interesting to see the diverse attitudes taken toward this strange one-day nonjob. With a young, handsome, tightly framed volunteer, blips like his knitted turtleneck or an earring fill in the space partitioned for character, on top of Everson’s tribute to the limitless expressions of the face: coy smiles (baring teeth, concealing), deep concentration, a mind in thrall to Zen nonthought, and so on. Another volunteer—a Black woman with braided hair—is decidedly chipper each time she has to greet a new voter. She beams as if she’s on a daytime game show: “Come on down!” she keeps saying, making everyone feel like they’re the next contestant on The Price Is Right. Everson nails the rhythm of a day in which thrill-pumped acts are spaced out Morse code–style by dashes of waiting, of emergence.

Everson has said, “We want things to be reality. I think it’s the same as in literature. . . . Ever since 1839 that whole idea of representing what was real got kind of stuck to the culture. With photo—ever since the invention of photography we’re just doomed.”11 So much of the lived experience of neocolonial subjects gets integrated, with the speed of a camera shutter, into data, bureaucratic information, violent reductions of the possibilities of life arrested at the moment of their imagining.12 Everson, by contrast, rejects the instant. He reacts against today’s social mediation of time as so many clips and detached climaxes and content. Whether his film is as short as a Lumière actuality or takes literally all day to watch, he delays the time it takes the human eye to understand a scene. Pressure is placed on perception, on codes that we have been trained to accept at face value for over a century. What happens when the unseen violence of centuries of racist brutality is revealed, burbling alongside (not beneath) a surface, known but unknown? What happens when linear time not only slows down but shatters? What happens when attention in our fast times is recirculated to pick up the throwaway gestures of women at work, of men making art in between inhales and exhales? Everson provides a radical glimpse into such an old-and-new world.

Most of the films discussed in this essay appear on the following home-video releases: Second Run’s How You Live Your Story, a stellar two-disc (region-free) Blu-ray set of several Everson features and shorts, selected by the artist himself; Video Data Bank’s three-disc box set Broad Daylight and Other Times, featuring work from 2002–09; and the DVD I Really Hear That, focusing on labor-themed films. Park Lanes (2015) and Everson’s Black Fire collaborations with historian and UVA colleague Claudrena N. Harold are available to stream on the Criterion Channel.

1From the author’s notes on “Blackness and Abstraction,” a weekly seminar attended by the author and taught by Kobena Mercer at Yale University, January–May 2020. See also Mercer, “Black Art and the Burden of Representation,” Third Text 4, no. 10 (Spring 1990), pp. 61–78.

2Tom Meisenhelder, “African Bodies: ‘Othering’ the African in Precolonial Europe,” Race, Gender & Class 10, no. 2, “Interdisciplinary Topics in Race, Gender, and Class” (2003), p. 111.

3Michael B. Gillespie, Film Blackness: American Cinema and the Idea of Black Film (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), quoted here from Jeff Scheible, “Throwing Punches: The Athletic Aesthetics of Kevin Jerome Everson’s Filmmaking,” World Records Journal 3, no. 3 (2019). Available online at https://vols.worldrecordsjournal.org/03/03 (accessed February 28, 2021).

4Gillespie, Film Blackness, p. 4.

5Ed Halter, “The Practice of Everyday Life,” Artforum 48, no. 9 (May 2010). Available online at https://www.artforum.com/film/ed-halter-on-kevin-jerome-everson-28020 (accessed March 1, 2021).

6Everson, liner notes to Broad Daylight and Other Times: Selected Works of Kevin Jerome Everson, DVD (Chicago: Video Data Bank, 2011).

7Everson, in Terri Francis, “Of the Ludic, the Blues, and the Counterfeit: An Interview with Kevin Jerome Everson, Experimental Filmmaker,” Black Camera 5, no. 1 (Fall 2013), p. 198.

8Note that due to the pandemic, the author saw the “work-from-home” edition of Park Lanes, which received its streaming premiere on the Criterion Channel in February 2021. On television, it has a completely different effect from the version most viewers and critics have seen: one wavers in and out more often, the droning endlessness of factory work is that much more pronounced because it infiltrates the space of the bourgeois living room, and the volume can be manipulated to placate neighbors or sleeping roommates.

9Hortense J. Spillers, “‘All The Things You Could Be by Now, if Sigmund Freud’s Wife Was Your Mother’: Psychoanalysis and Race,” boundary 2 23, no. 3 (Autumn 1996), p. 78.

10Ibid., p. 109.

11Everson, in Francis, “Of the Ludic,” p. 192.

12“Thinking about imperial violence in terms of a camera shutter means grasping its particular brevity and the spectrum of its rapidity.” Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (New York: Verso Books, 2019), p. 27.