Criticized at the time for an over-emphasis on white women and its stylized representations of vaginas, Judy Chicago’s room-sized installation The Dinner Party has only recently come to be seen as a canonical example of late-20th-century art.

Created over a five-year period (1974-79) and consisting of 39 elaborate place settings, it imagines a meal shared by notable women throughout history, such as Elizabeth I, Sojourner Truth, and the goddess Ishtar.

At times, The Dinner Party has overshadowed the rest of Chicago’s prodigious output, and she has professed a distaste for revisiting it or rethinking the list of invitees. When a museum director informed Chicago 40 years ago that it would be the culmination of her career, she says she responded with, “I’m just getting started.”

Indeed, she went on to create whole series on challenging or uncomfortable themes such as the Holocaust, birth, and toxic masculinity (long before that phrased gained currency).

A sweeping career survey at San Francisco’s de Young Museum confirms that The Dinner Party is only one of a number of Chicago’s monumental and often overlooked works, spanning painting, sculpture and needlecraft. Simply titled Judy Chicago: A Retrospective, it chronicles a six-decade career by an indefatigable artist who founded not one but two feminist-art programs, and adopted her name after a 1970 full-page ad in Artforum.

With little regard for the dictates of the art market, Chicago often worked at a very large scale, provoking audiences to have visceral responses to her pieces. Yet in spite of her facility with various media, she toiled in comparative obscurity for many years, her pieces languishing in storage or destroyed. The de Young’s exhibition is an overdue corrective.

“I used to refer to Rainbow Pickett as the piece that broke my heart, because now people refer to it as a masterpiece. But there was no interest in it in the ’60s, and I destroyed it,” Chicago told the Guardian at the retrospective’s opening last week. “It’s been very interesting to discover that work I did a long time ago had aesthetic potential that I didn’t understand at the time.”

Curator Claudia Schmuckli chose to present Chicago’s works in reverse chronological order. This stylistic decision foregrounds The End, Chicago’s series on extinction and environmental plunder, leading to her needlework-heavy Birth Series and the dynamic male faces and bodies of PowerPlay.

“One thing that I think is completely under-appreciated about Judy is the rigor of her intellectual research,” Schmuckli said. “Whether that’s the development of the color scheme or the choice of material, everything is carefully considered and has in it years and years of experimentation, research and writing.”

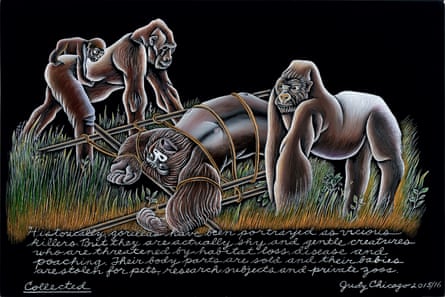

Chicago spent eight years researching her Holocaust series, an especially long time when you realize that she had no idea whether pieces on that subject would even sell. For her, writing isn’t detached from visual art, but a component of it. In The End, a liberal use of explanatory text accompanies discomfiting images of mutilated sharks or yew trees stripped of their bark to produce medications to treat cancer.

“I didn’t know how to make my form speak fully, and so I’ve gone back and forth from using text,” Chicago said, referring to The End. “I felt, in order to understand the images, there is information you needed to know. When a yew tree’s bark is stripped, they die. Isn’t there a way to plunder nature where we also restore nature?”

Calling Chicago a “very accessible artist”, Thomas Campbell, the director of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, observed that viewers don’t “require knowledge of either critical theory or art history” in order for her work to be legible.

Ever prescient, the artist agrees, taking a democratic approach toward art’s capacity for social change.

Art matters, Chicago said, “only if it deals with issues that people care about, in ways that they can understand. If it does, I believe art has the power to educate, empower and inspire viewers, a task made more urgent by the world we find ourselves facing.”

The Dinner Party itself, currently at New York’s Brooklyn Museum, is represented at Judy Chicago: A Retrospective through test plates, preparatory sketches, and a making-of film. Otherwise, the de Young sourced work from several significant phases in Chicago’s career, like The Fall, the visceral jewel of her Holocaust Project, to the pastel-hued 1960s sculptural abstractions she fashioned during the heyday of the Light and Space movement.

Notable for a retrospective this thorough is a companion exhibition at San Francisco’s Jessica Silverman gallery. There, Judy Chicago: Human Geometries includes numerous little-seen works centered on a reproduction Sunset Squares, a since-destroyed quartet of rearrangeable structures that frame their surroundings, in a feminist response to the male-dominated Land Art movement. (“I’m that little lady who made all this big stuff!” Silverman says Chicago told the installers.)

“She understands the art history of color very profoundly, and also how color responds to different materials,” Silverman says. “In the paintings from the ’60s to a porcelain paint work made in 2021, she really thinks about these blends, the way colors meet each other and integrate.”

Together with A Retrospective, the result is a sweeping evaluation of a major talent. “Overcoming the erasure of women’s values continues to be one of my goals,” Chicago said. Only now has her 60-year body of work earned the same treatment.