Childhood is one great brush-stroke of loneliness, thick and pastel-colored, its edges blurring out into the whole landscape of life.

In this blur of being by ourselves, we learn to be ourselves. One measure of maturity might be how well we grow to transmute that elemental loneliness into the “fruitful monotony” Bertrand Russell placed at the heart of our flourishing, the “fertile solitude” Adam Phillips recognized as the pulse-beat of our creative power.

If we are lucky enough, or perhaps lonely enough, we learn to reach out from this primal loneliness to other lonelinesses — Neruda’s hand through the fence, Kafka’s “hand outstretched in the darkness” — in that great gesture of connection we call art.

Rilke, contemplating the lonely patience of creative work that every artist knows in their marrow, captured this in his lamentation that “works of art are of an infinite loneliness” — Rilke, who all his life celebrated solitude as the groundwater of love and creativity, and who so ardently believed that to devote yourself to art, you must not “let your solitude obscure the presence of something within it that wants to emerge.”

Giuliano Cucco (1929–2006) was still a boy, living with his parents amid the majestic solitudes of rural Italy, when the common loneliness of childhood pressed against his uncommon gift and the artistic impulse began to emerge, tender and tectonic.

Over the decades that followed, he grew volcanic with painting and poetry, with photographs and pastels, with art ablaze with a luminous love of life.

When Cucco moved to Rome as a young artist, he met the young American nature writer John Miller. A beautiful friendship came abloom. Those were the early 1960, when Rachel Carson — the poet laureate of nature writing — had just awakened the modern ecological conscience and was using her hard-earned stature to issue the radical insistence that children’s sense of wonder is the key to conservation.

Into this cultural atmosphere, Cucco and Miller joined their gifts to create a series of stunning and soulful nature-inspired children’s books.

John Miller (left) and Giuliano Cucco in the 1960s

But when Miller returned to New York, door after door shut in his face — commercial publishers were unwilling to invest in the then-costly reproduction of Cucco’s vibrant art. It took half a century of countercultural courage and Moore’s law for Brooklyn-based independent powerhouse Enchanted Lion to take a risk on these forgotten vintage treasures and bring them to life.

Eager to reconnect with his old friend and share the exuberant news, Miller endeavored to track down Cucco’s family. But when he finally reached them after a long search, he was devastated to learn that the artist and his wife had been killed by a motor scooter speeding through a pedestrian crossing in Rome.

Giuliano Cucco, self-portrait

Their son had just begun making his way through a trove of his father’s paintings — many unseen by the world, many depicting the landscapes and dreamscapes of childhood that shaped his art.

Because grief is so often our portal to beauty and aliveness, Miller set out to honor his friend by bringing his story to life in an uncommonly original and tender way — traveling back in time on the wings of memory and imagination, to the lush and lonesome childhood in which the artist’s gift was forged, projecting himself into the boy’s heart and mind through the grown man’s surviving paintings, blurring fact and fancy.

Before I Grew Up (public library) was born — part elegy and part exultation, reverencing the vibrancy of life: the life of feeling and of the imagination, the life of landscape and of light, the life of nature and of the impulse for beauty that irradiates what is truest and most beautiful about human nature.

In spare, lyrical first-person narrative spoken by the half-real, half-imagined boy becoming an artist, Miller invokes the spirit of Giuliano’s childhood. Emanating from it is the universal spirit of childhood — that infinity-pool of the imagination, which prompted Baudelaire to declare that “genius is nothing more nor less than childhood recovered at will.”

In my room, I had my own workbench, where I made paper boats and let them float away like dreams.

In my room, I had my own workbench, where I made paper boats and let them float away like dreams.

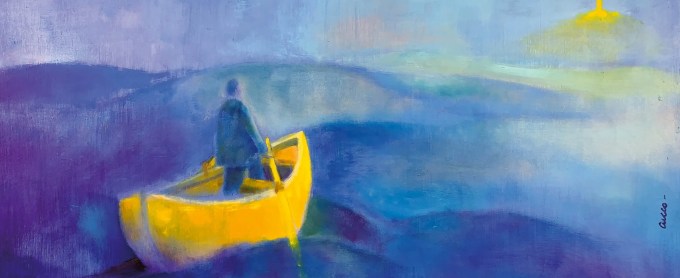

We feel the boy’s imaginative loneliness deepen when we encounter his father, brilliant and remote — “a scientist who studied where light came from — not sunlight, but another kind of light he said was inaccessible,” and who talked little and “preferred to ride his bicycle to the ocean and row out among the waves in a tippy row boat, looking for the light.”

The mother never appears, in the paintings or in the story. But her garden is a refuge where the boy goes to watch tulips bloom. “There, I was never lonely,” he says in that way of self-persuasion we have with reality.

There, he dreams of flying up and away like a bird, soaring into the sky above the flowers, savoring the light and life of nature, there in the remote countryside.

But then his parents decide to send him to city, so that he may learn the life of culture. Staying with his aunt and uncle, watching the adults busy themselves with the attractive distractions of adulthood, he once again travels to wondrous worlds in his imagination.

In a gust of gladness, the boy returns to the country to meander between far-neighboring houses, to climb rooftop towers, to fly his kite into the light.

One day, when the boy is twelve, his father rows out to the ocean to look for his invisible light and returns with a tale of water so calm that he stood up in his tippy row boat and played his violin.

From this static scene depicted in one of Cucco’s real paintings, from the known facts of his friend’s life, in the voice of the boy about to be lit up by his creative calling, Miller’s soaring imagination conjures up a larger poetic truth about what it means to be an artist, about the meaning of love and the measure of enough, about the slender strands of assurance that weave the lifeline of the creative spirit.

Here’s a picture I painted from what he told me.

Here’s a picture I painted from what he told me.

After, I asked him if I had painted the light he was seeking.

My father wasn’t much of a talker, but this time he said these three words: “Yes, you did.”

That was enough.

From then on, I knew I would grow up to be an artist.

Complement Before I Grew Up — to the lyric splendor and tactile vibrancy of which no summation or screen does justice — with the illustrated life of Corita Kent, another underheralded artist of uncommon vision and largeness of heart. For a science counterpart, savor the illustrated life of Edwin Hubble, who revolutionized our understanding of the universe with his search for a different kind of light.

Almost everything I write, I “write” in the notebook of the mind, with the foot in motion — what happens at the keyboard upon returning from the long daily walks that sustain me is mostly the work of transcription.

I am far from alone in the reliance on ambulatory solitude as an anchor of creative practice — there is Rebecca Solnit’s lovely definition of walking as “a state in which the mind, the body, and the world are aligned,” and Thomas Bernhard’s insight that “there is nothing more revealing than to see a thinking person walking, just as there is nothing more revealing than to see a walking person thinking,” and Wind in the Willows author Kenneth Grahame’s insistence that solitary walks “set the mind jogging… make it garrulous, exalted, a little mad maybe — certainly creative and suprasensitive,” and of course Thoreau, always Thoreau, who believed that “every walk is a sort of crusade” for returning to our senses.

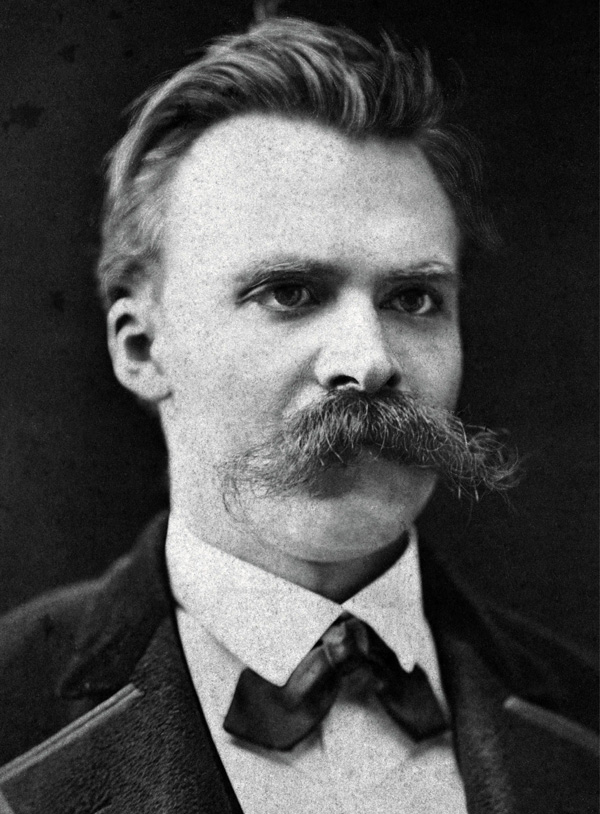

But hardly any thinker has been shaped and saved by walking more powerfully than Friedrich Nietzsche (October 15, 1844–August 25, 1900).

Friedrich Nietzsche

In his early thirties, intellectually alienated by an academic world unripe for his ideas, romantically deflated after one too many hasty marriage proposals spurned, Nietzsche was leveled by spells of nausea and increasingly debilitating migraines that left him bedridden in a darkened chamber for days at a time, unable to read or write, his eyes daggers of pain. He found only one remedy — long solitary walks.

In the summer of his thirty-third year, having exiled himself to a succession of temporary lodgings across Europe, he wrote from amid the pines of the Black Forest:

I am walking a lot, through the forest, and having tremendous conversations with myself.

I am walking a lot, through the forest, and having tremendous conversations with myself.

A fellow looper, Nietzsche walked the same routes one hour every morning and three every afternoon, half-blind, dreaming of having a small house of his own someplace solitary and walkable:

I would walk for six or eight hours a day, composing thoughts that I would later jot down on paper.

I would walk for six or eight hours a day, composing thoughts that I would later jot down on paper.

That summer, he composed The Wanderer and His Shadow — the third and final installment in his aphoristic roadmap to becoming oneself — almost entirely on foot, filling six small notebooks with penciled-in peripatetic thoughts. In it, he considered “the wanderings of the reason and the imagination” by which one becomes a truly free spirit — wanderings that, for him, took place with the mind afoot across mountains and meadows. Long before modern science shed light on the role of the hippocampus in how landscapes shape us, Nietzsche became himself in his wanderings.

Major rivers and mountains of the world compared by length and height, from Atlas de Choix, 1829. (Available as a print, a face mask, stationery cards, and a backpack, benefitting The Nature Conservancy.)

Even in his exile, even in the agony of his social ostracism and the agony between his temples, Nietzsche never lost sight of how provisional and relative privilege is, how lucky he was to have this lifeline:

During my long walks I had wept too much, and not sentimental tears but tears of happiness, singing and staggering, taken over by a new gaze that marks my privilege over the men of today.

During my long walks I had wept too much, and not sentimental tears but tears of happiness, singing and staggering, taken over by a new gaze that marks my privilege over the men of today.

By his mid-thirties, he was doing “ten hours a day of hermit’s walking.” This was his personal Golden Age, his decade of walking and writing the books that would leave his immortal trail: Zarathustra, The Dawn, Beyond Good and Evil, The Joyous Science, On the Genealogy of Morality. In one of them, he wrote:

We do not belong to those who have ideas only among books, when stimulated by books. It is our habit to think outdoors — walking, leaping, climbing, dancing, preferably on lonely mountains or near the sea where even the trails become thoughtful.

We do not belong to those who have ideas only among books, when stimulated by books. It is our habit to think outdoors — walking, leaping, climbing, dancing, preferably on lonely mountains or near the sea where even the trails become thoughtful.

Spring Moon at Ninomiya Beach, 1931 — one of Hasui Kawase’s vintage Japanese woodblocks. (Available as a print.)

A virtuoso of metaphor, he adds:

Our first questions about the value of a book, of a human being, or a musical composition are: Can they walk? Even more, can they dance?

Our first questions about the value of a book, of a human being, or a musical composition are: Can they walk? Even more, can they dance?

Good books, Nietzsche believed, are spacious books — books that breathe the same open air in which the ideas set down in them forged; bad books exude the cramped smallness in which they were written — works of “closet air, closet ceilings, closet narrowness.” We write, he believed, “only with our feet.” Having declaimed that “without music life would be a mistake,” he held his most cherished art to the same standard:

What my foot demands in the first place from music is that ecstasy which lies in good walking.

What my foot demands in the first place from music is that ecstasy which lies in good walking.

And so it comes as no surprise that he made walking a centerpiece of his philosophy, manifested in his most fertile thought experiment — the Eternal Return, or Eternal Recurrence. In A Philosophy of Walking (public library), where Nietzsche’s relationship with the mind in motion figures prominently, Frédéric Gros writes:

When one has walked a long way to reach the turning in the path that discloses an anticipated view, and that view appears, there is always a vibration of the landscape. It is repeated in the walker’s body. The harmony of the two presences, like two strings in tune, each feeding off the vibration of the other, is like an endless relaunch. Eternal Recurrence is the unfolding in a continuous circle of the repetition of those two affirmations, the circular transformation of the vibration of the presences. The walker’s immobility facing that of the landscape… it is the very intensity of that co-presence that gives birth to an indefinite circularity of exchanges: I have always been here, tomorrow, contemplating this landscape.

When one has walked a long way to reach the turning in the path that discloses an anticipated view, and that view appears, there is always a vibration of the landscape. It is repeated in the walker’s body. The harmony of the two presences, like two strings in tune, each feeding off the vibration of the other, is like an endless relaunch. Eternal Recurrence is the unfolding in a continuous circle of the repetition of those two affirmations, the circular transformation of the vibration of the presences. The walker’s immobility facing that of the landscape… it is the very intensity of that co-presence that gives birth to an indefinite circularity of exchanges: I have always been here, tomorrow, contemplating this landscape.

Afoot by Maria Popova

In his final book, Nietzsche bequeathed his life-tested advice on the life of the mind and the life of the spirit:

Sit as little as possible; do not believe any idea that was not born in the open air and of free movement — in which the muscles do not also revel… Sitting still… is the real sin against the Holy Ghost.

Sit as little as possible; do not believe any idea that was not born in the open air and of free movement — in which the muscles do not also revel… Sitting still… is the real sin against the Holy Ghost.

Complement with the great Scottish mountaineer and poet Nan Shepherd on the moving body as an instrument of the mind and Lauren Elkin’s splendid contemporary manifesto for walking as creative empowerment, then revisit Nietzsche on love and perseverance, how to find yourself, why a fulfilling life requires embracing rather than running from difficulty, depression and the rehabilitation of hope, and the power of music, the power of language.

“The logic of dreams is superior to the one we exercise while awake,” the artist, philosopher, and poet Etel Adnan wrote as she considered creativity and the nocturnal imagination. It is an insight that transcends the abstract imagination of art to reach into the heart of reason itself, touching the crucible of consciousness and everything that makes the matter huddled in the cranial cave a mind. After all, we are born dreaming and spend a third of our lives in the unconscious reaches of the night. Often, what we find there surprises us, even though we ourselves originated it, being always both the dreamer and the dreamt. Sometimes, what we find there awakens us to revelations our conscious mind has grasped for but failed to seize, bringing into our waking lives breakthroughs of understanding that forever change the course of our ordinary thought.

That is what theoretical cosmologist, jazz virtuoso, and my occasional poetic collaborator Stephon Alexander explores in one of the most fascinating and satisfying portions of Fear of a Black Universe: An Outsider’s Guide to the Future of Physics (public library) — his brief yet undiluted history of the most groundbreaking discoveries that have shaped our understanding of the universe, peering into the unlit horizons of its future. Emerging from the pages is a broader meditation on how these fathomless leaps were made — “how a theoretical physicist dreams up new ideas and sharpens them into a consistent framework” — in ways often unexpected, sometimes seemingly inexplicable, and almost always arisen from minds that were in some way other, pulsating with the quiet power of pariahood, symphonic with the same outsiderdom that made Blake and Beethoven who they were, thinking in ways orthogonal to the common tracks and playing with forms of not-thinking that vivify the dead-ends of thought.

Stephon Alexander at The Universe in Verse, 2019.

Reflecting on Einstein’s epoch-making reckonings with the unseen nature of reality, which began in little Albert’s childhood encounter with the compass that gave him the intuitive sense that “something deeply hidden had to be behind things,” Alexander writes:

A scientist should make connections and see patterns across a range of experimental outcomes, which may not be related to each other in an obvious way. Once the scientist ekes out these patterns, she makes a judgment call as to whether a new principle of nature is necessary. But this is misleading. Facts are statements about phenomena, but they don’t exist on their own; they are always conceptualized, which means that they are, if only implicitly, constructed theoretically. Experiments allow us to answer theoretically constructed questions. Theory tells us what “facts” to look for.

A scientist should make connections and see patterns across a range of experimental outcomes, which may not be related to each other in an obvious way. Once the scientist ekes out these patterns, she makes a judgment call as to whether a new principle of nature is necessary. But this is misleading. Facts are statements about phenomena, but they don’t exist on their own; they are always conceptualized, which means that they are, if only implicitly, constructed theoretically. Experiments allow us to answer theoretically constructed questions. Theory tells us what “facts” to look for.

In consonance with physicist Chiara Marletto’s case for how the science of counterfactuals expands the horizons of the possible, he adds:

Sometimes to get around a scientific problem, one must consider possibilities that defy the rules of the game. If you don’t enable your mind to freely create sometimes strange and uncomfortable new ideas, no matter how absurd they seem, no matter how others view your arguments or punish you for making them, you may miss the solution to the problem. Of course, to do this successfully, it is important to have the necessary technical tools to turn the strange idea into a determinate theory.

Sometimes to get around a scientific problem, one must consider possibilities that defy the rules of the game. If you don’t enable your mind to freely create sometimes strange and uncomfortable new ideas, no matter how absurd they seem, no matter how others view your arguments or punish you for making them, you may miss the solution to the problem. Of course, to do this successfully, it is important to have the necessary technical tools to turn the strange idea into a determinate theory.

[…]

The exercise of journeying into a theoretical territory and then journeying back has proven time and time again to be useful in surveying what’s possible and, hopefully, what describes and predicts the real universe.

“Spectra of various light sources, solar, stellar, metallic, gaseous, electric” from Les phénomènes de la physique by Amédée Guillemin, 1882. (Available as a print, a face mask, and a fanny pack, benefitting The Nature Conservancy.)

Often, scientists journey on the wings of thought experiments — playthings of the mind, modeling physical events made possible by the laws of the universe but impossible to carry out experimentally with our earthbound tools. (This technique, of course, might be fundamental to just how the human mind makes sense, deployed not only by scientists but also by philosophers at least as far back as The Ship of Theseus — the Ancient Greek thought experiment that remains our best model of the self — and into Nietzsche’s Eternal Return, and into what might be my favorite: the vampire problem.)

Even in science, these reconnaissance rovers of the possible sometimes launch from uncommon places; sometimes, the laboratory of the mind is outside the mind — at least outside the common waking consciousness by which we reason, speculate, and sensemake. There is the iconic case of Einstein’s dreams, so splendidly brought to life by physicist and novelist Alan Lightman. There is Mendeleev discovering his periodic table in a dream. Such profound dream-state breakthroughs of insight into waking reality are not limited to science — there is Dostoyevsky discovering the meaning of life in a dream, and Margaret Mead discovering the meaning of life in a dream.

Illustration by Vladimir Radunsky for On a Beam of Light: A Story of Albert Einstein by Jennifer Berne

With an eye to Einstein’s masterpiece of the mind, Alexander writes:

Beginning when Einstein was a teenager hanging out in his father’s electric lighting company, he would play with imaginations about the nature of light. He would try to become one with a beam of light and wondered what he would see if he could catch up to a light wave. This matter found itself in the playground of Einstein’s subconscious and revealed a paradox in a dream. It is said that Einstein dreamt of himself overlooking a peaceful green meadow with cows grazing next to a straight fence. At the end of the fence was a sadistic farmer who occasionally pulled a switch that sent an electrical current down the fence. From Einstein’s birds-eye view he saw all the electrocuted cows simultaneously jump up. When Einstein confronted the devious farmer, there was a disagreement as to what happened. The farmer persisted that he saw the cows cascade in a wavelike motion. Einstein disagreed. Both went back and forth with no resolution. Einstein woke up from this dream with a paradox.

Beginning when Einstein was a teenager hanging out in his father’s electric lighting company, he would play with imaginations about the nature of light. He would try to become one with a beam of light and wondered what he would see if he could catch up to a light wave. This matter found itself in the playground of Einstein’s subconscious and revealed a paradox in a dream. It is said that Einstein dreamt of himself overlooking a peaceful green meadow with cows grazing next to a straight fence. At the end of the fence was a sadistic farmer who occasionally pulled a switch that sent an electrical current down the fence. From Einstein’s birds-eye view he saw all the electrocuted cows simultaneously jump up. When Einstein confronted the devious farmer, there was a disagreement as to what happened. The farmer persisted that he saw the cows cascade in a wavelike motion. Einstein disagreed. Both went back and forth with no resolution. Einstein woke up from this dream with a paradox.

In the account of Einstein’s dream, and other accounts of the role of dreams in creative work, such as music, science, and visual art, there is a common theme: a paradox is revealed through imaginations that are contradictory in the awake state.

Alexander’s own scientific trajectory was pivoted by a dream-state insight.

As a young scientist, after many spurned applications, he finally got an appointment as a postdoctoral researcher at Imperial College in London, working with some of the living luminaries of theoretical physics. Immediately seized with impostor syndrome, he found his mind, ordinarily “volcanic with ideas,” in an ashen stupor. He considered becoming a high school physics teacher. He considered leaving physics altogether and devoting himself wholly to jazz.

Then, one day, the head of his theory group summoned Alexander to his office. Chris Isham — “a tall Englishman with dark hair and piercing eyes and who walked with a slight limp,” living with a rare neurological disorder, just like his friend and former classmate Stephen Hawking — was a widely revered virtuoso of mathematical physics and quantum gravity.

When Isham asked the young American physicist why he was at Imperial College, Alexander flinched with the tenderly human fear that he was about to be called out for being a fraud. But he answered with a scientist’s clarity and a Stoic’s composure: “I want to be a good physicist.”

Isham’s response stunned him: “Then stop reading those physics books!” Pointing to a dedicated bookshelf in his office containing the complete works of Carl Jung, he instructed Alexander to begin writing down his dreams, which they would discuss in weekly sessions at Isham’s office. He then urged him to read Atom & Archetype — the record of Jung’s improbable friendship with the Nobel-winning physicist Wolfgang Pauli, who had originally turned to him for dream analysis but who ended up collaborating with the famed psychiatrist to bridge mind and matter in the invention of synchronicity.

Illustration by Tom Seidmann-Freud — Sigmund Freud’s gender-diverse niece — from a philosophical 1922 children’s book about dreaming.

Alexander obliged, welcoming this uncommon invitation to spend time with his scientific hero. And then came the dream that shaped his own science. He writes:

As the weeks passed, I told Isham about what I thought was a trivial dream. In Jungian philosophy, dreams sometimes allow us to confront our shadows with the appearances of symbols called archetypes. I saw one here. I was suspended in outer space and an old, bearded man in a white robe — it wasn’t God — was silently and rapidly scribbling incomprehensible equations on a whiteboard. I admitted to the old man that I was too dumb to know what he was trying to show me. Then the board disappeared, and the old man made a spiraling motion with his right hand. Isham was captivated by this dream and asked, “What direction was he rotating his hands?” I was baffled as to why he was interested in this detail.

As the weeks passed, I told Isham about what I thought was a trivial dream. In Jungian philosophy, dreams sometimes allow us to confront our shadows with the appearances of symbols called archetypes. I saw one here. I was suspended in outer space and an old, bearded man in a white robe — it wasn’t God — was silently and rapidly scribbling incomprehensible equations on a whiteboard. I admitted to the old man that I was too dumb to know what he was trying to show me. Then the board disappeared, and the old man made a spiraling motion with his right hand. Isham was captivated by this dream and asked, “What direction was he rotating his hands?” I was baffled as to why he was interested in this detail.

But two years later, while I was a new postdoc at Stanford, I was working on one of the big mysteries in cosmology — the origin of matter in the universe — when the dream reappeared and provided the key insight to constructing a new mechanism based on the phenomenon of cosmic inflation, the rapid expansion of space in the early universe. The direction of rotation of the old man’s hand gave me the idea that the expansion of space during inflation would be related to a symmetry that resembled a corkscrew motion that elementary particles have called helicity. The resulting publication was key to earning me tenure and a national award from the American Physics Society.

Reflecting on the fertility of this unconscious work in the dream-world — work that springs from the same consciousness with which we make sense of the ordinary world of touch and thought — Alexander adds:

Perhaps dreams are an arena that can enable supracognitive powers to perform calculations and perceptions of reality that may be incomprehensible in our wake state. In my case, my paradox was making an equivalence between incomprehensible equations presented by the bearded man and his counterclockwise whirling hands. This counterclockwise motion turned out to summarize the mathematics that was obscuring the underlying physics to be unveiled.

Perhaps dreams are an arena that can enable supracognitive powers to perform calculations and perceptions of reality that may be incomprehensible in our wake state. In my case, my paradox was making an equivalence between incomprehensible equations presented by the bearded man and his counterclockwise whirling hands. This counterclockwise motion turned out to summarize the mathematics that was obscuring the underlying physics to be unveiled.

Underlying such experiences is the question that first pulled Alexander to physics, inspired by the work of his great hero, the boldly outsider-minded Erwin Schrödinger: “What is the relationship between consciousness and the fabric of the universe?”

Erwin Schrödinger, circa 1920s.

Alongside pioneering quantum mechanics — and perhaps in order to be able to pioneer quantum mechanics — Schrödinger dared to reach far beyond the common contours of Western science, into poetry, into color theory, into the ancient Eastern philosophical traditions, into the most elemental strata of being, to ask question about life and death and the ongoing mystery of consciousness.

Schrödinger looked for the answers of his scientific inquiries not only in uncommon places, but in uncommon ways.

When Einstein won his Nobel Prize for demonstrating that light can behave not only like a wave, but like a quantum particle — the photon, born of the harmonic vibrations we call quanta — the wave-particle duality hurled the world of science into a discord of comprehension. And then Schrödinger returned from a skiing trip with an elegant and revolutionary equation describing for the first time the wavelike behavior of electrons, laying bare the dream for a wave function of the entire universe.

That selfsame year, 1926, while pondering the nature of consciousness, Virginia Woolf described all creative breakthrough as the product of “a wave in the mind.”

Woolf would come to write that “our minds are all threaded together… & all the world is mind.” Schrödinger would come to compose the part-koan, part-aphorism, part Wittgensteinian declarative statement that “the total number of minds in the universe is one.”

Plate from An Original Theory or New Hypothesis of the Universe by Thomas Wright, 1750. (Available as a print, as a face mask, and as stationery cards.)

Shortly after Woolf’s death, Schrödinger published some of his ideas linking mind and matter in a slender, daring book titled What Is Life? — part thought experiment and part theoretical manual for the future. Bridging the laws of physics that give stars light with the biochemical processes that give us life, he sought to understand, by leaning on the quantum world, how something as complex as the consciousness that animates us can arise from inanimate matter.

Epochs ahead of their time, Schrödinger’s propositions not only shaped the course of physics but inspired the research that led to the discovery of the structure and function of DNA, which made tangible the ambiguous and amorphous idea of the genetic unit of inheritance that had been rippling across the collective mind of science. Alexander writes:

Schrödinger opens his argument by conjuring quantum mechanics as the starting point to understand the difference between nonliving and living matter. For example, the bulk properties of a piece of metal, such as its rigidity and ability to conduct electrons, require an emergent long-range order [which] should be a result of the bonding mechanism and the collective effects of the quantum wavelike properties of electrons in the metal’s atoms. Schrödinger then describes how the atoms in inanimate matter can organize themselves spatially in a periodic crystal, before making a daring leap. Life clearly is more complicated and variable than a piece of metal, so periodicity isn’t going to cut it. So Schrödinger makes a bold proposal: that some key processes in living matter should be governed by aperiodic crystals. More astonishing, Schrödinger postulates this nonrepetitive molecular structure — which will turn out to be a great description of DNA — should house a “code-script” that would give rise to “the entire pattern of the individual’s future development and of its functioning in the mature state.”

Schrödinger opens his argument by conjuring quantum mechanics as the starting point to understand the difference between nonliving and living matter. For example, the bulk properties of a piece of metal, such as its rigidity and ability to conduct electrons, require an emergent long-range order [which] should be a result of the bonding mechanism and the collective effects of the quantum wavelike properties of electrons in the metal’s atoms. Schrödinger then describes how the atoms in inanimate matter can organize themselves spatially in a periodic crystal, before making a daring leap. Life clearly is more complicated and variable than a piece of metal, so periodicity isn’t going to cut it. So Schrödinger makes a bold proposal: that some key processes in living matter should be governed by aperiodic crystals. More astonishing, Schrödinger postulates this nonrepetitive molecular structure — which will turn out to be a great description of DNA — should house a “code-script” that would give rise to “the entire pattern of the individual’s future development and of its functioning in the mature state.”

Planted into other fertile and unorthodox minds, these ideas went on to seed the founding principles of information theory (in Claude Shannon’s mind) and cybernetics (in Norbert Weiner’s mind), shaping the modern world — the world in which I am extracting these thoughts from my atomic mind, externalizing them by pressing some keys over a circuitboard, and transmitting them to you via bits that you receive on a digital screen to metabolize with your own atomic mind. Here we are, thinking together, threaded together across the globe by fiber optic cables and relativity. All the world is mind, woven of matter.

Art from Thomas Wright’s An Original Theory or New Hypothesis of the Universe, 1750. (Available as a print, a face mask, and coasters, benefitting The Nature Conservancy.)

More than that, Schrödinger’s inquiry into the relationship between life and non-life, between mind and matter, fomented a new wave of uneasy excitement about the nature of consciousness, washing up ashore what might be the most controversial, misunderstood, and daring theory of consciousness: panpsychism, rooted in the idea that “consciousness is an intrinsic property of matter, the same way that mass, charge, and spin are intrinsic to an electron.”

Clarifying the theory’s central premise of a “nonlocal conscious observer” — which, to be clear, is not a science-cloaked euphemism for “God,” as much as certain spiritual factions have attempted to appropriate quantum science for their ideological purposes in the century since its dawn — Alexander writes:

Let us assume that consciousness, like charge and quantum spin, is fundamental and exists in all matter to varying degrees of complexity. Therefore consciousness is a universal quantum property that resides in all the basic fields of nature — a cosmic glue that connects all fields as a perceiving network.

Let us assume that consciousness, like charge and quantum spin, is fundamental and exists in all matter to varying degrees of complexity. Therefore consciousness is a universal quantum property that resides in all the basic fields of nature — a cosmic glue that connects all fields as a perceiving network.

More than a century after the uncommonly minded Canadian psychiatrist Maurice Bucke posited his theory of “cosmic consciousness,” which influenced generations of thinkers ranging from Einstein to Maslow to Steve Jobs, Alexander probes the real physics underpinning this speculative model:

The expansion of the early universe linked with the flow of entropy necessary for biological life is a hint at a deeper interdependence between life and the quantum universe. Did life emerge in the cosmos through a series of accidental historical events? Is there a deeper principle beyond natural selection at work that is encoded in the structure of physical law? And on top of that, the question that bothered Schrödinger and that got me into science in the first place: What is the relationship between consciousness and the fabric of the universe?

The expansion of the early universe linked with the flow of entropy necessary for biological life is a hint at a deeper interdependence between life and the quantum universe. Did life emerge in the cosmos through a series of accidental historical events? Is there a deeper principle beyond natural selection at work that is encoded in the structure of physical law? And on top of that, the question that bothered Schrödinger and that got me into science in the first place: What is the relationship between consciousness and the fabric of the universe?

[…]

Answering these questions might call into question the idea that the world out there is independent of us being there.

In the remainder of Fear of a Black Universe, he shines a sidewise gleam on these questions by detailing some of the most exhilarating discoveries and ongoing mysteries of science — how the still-uncertain constituent we have called dark matter keeps Earth’s orbit accountable to the assuring certainty that tomorrow arrives tomorrow, what the symmetry of geometrical objects has to do with the fabric of spacetime that hammocks our lives, whether space and time would cease to exist if gravity vanishes, and how ancient Babylonian, West African, and Indian creation cosmogonies contour the quantum quest for a wave function of the universe.