Character Sketches: Kurt Waldheim by Brian Urquhart

I have written about Kurt Waldheim not only because I worked with him for ten years, but also because his story sheds light on many of the peculiarities of international life – the lackadaisical attitude of the most powerful governments toward the United Nations, the triumph of ambition and persistent mediocrity, and the extent to which public figures can, for a time at least, get away with telling lies about themselves.

In 1971 Kurt Waldheim of Austria and Max Jakobson of Finland were the rival candidates to replace U Thant as Secretary-General of the United Nations. I knew Jakobson as a forthright and thoughtful ambassador. I had met Kurt Waldheim several times when he was the Austrian ambassador to the UN, but he had left little impression. The five permanent members of the Security Council, still in shock from the dynamism of Dag Hammarskjöld, had evidently identified Waldheim as someone who would not make waves or rock the boat, and he won the contest.

Waldheim had little public standing except as an unmemorable foreign minister of Austria, but that did not prevent him, on arrival at the UN, from posing as a world statesman who would radically upgrade the UN and its Secretariat. He was dismissive, even contemptuous, of his predecessors, an attitude that I was not prepared to accept in silence. He evidently regarded me as a representative of the old order which, with his superior wisdom and expertise, he was going to sweep away. I could, of course, have left in disgust, but the UN was my vocation and I had always felt that I worked for the institution rather than for some transient secretary-general. I was also determined to try to carry on the tradition of international service created by Dag Hammarskjold and Ralph Bunche.

At the time, the Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs was a key senior official in the UN Secretariat. Ralph Bunche, who had occupied the post for nearly twenty years, had died three months earlier and had not been replaced, and I was running his office, so inevitably I saw a great deal of the new Secretary-General. Much of the time he was insufferable. (We were exactly the same age). Waldheim had not yet understood the peculiar nature of his new job and routinely blamed his early mistakes on his subordinates, particularly those who had tried to prevent them. He was acutely nervous of governmental criticism or public disapproval.

At one of our early meetings, on the dangerous situation in the Indian subcontinent, Waldheim was particularly rude, in front of a number of other people, to me and one of my colleagues. After the meeting, I told him that, because he was the Secretary-General of the UN, I would never respond to his offensive remarks in front of other people. If, however, he insulted me again in front of others, I would resign and would not hesitate to explain to the press, governments, and anyone else who was interested, why I had done so. Waldheim apologized handsomely, and he was never rude to me again. I like to think that he also began to treat other members of his staff with more respect.

I gradually began to realize that Waldheim had qualities that did not readily present themselves to casual acquaintances or to the public. He was conscientious, hardworking, and had great physical stamina. Once he accepted an idea, he was prepared to follow it up, and he was never too tired to undertake an awkward journey, have an unpleasant interview, or make a difficult telephone call. For his part, Waldheim began to find out who actually did the work in the Secretariat, and on whom he could rely. He also realized that people who disagreed with him might sometimes be right and were therefore more useful than yes-men. He discovered that my office had a lot of experience in running difficult operations, was rather good at it, and that we were respected and trusted by governments.

In 1973, the October, or Yom Kippur, war in the Middle East, a serious enough crisis on its own account, developed into a dangerous potential confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union. The creation and rapid deployment of a UN peacekeeping force to pin down the very shaky ceasefire between Israel and Egypt seemed to be only practical way to eliminate this threat. When the Security Council called urgently for such a force, we had a plan ready which the Council approved the same day, and we were able to get soldiers on the ground between the Israelis and the Egyptians within 17 hours of the Council’s decision, thus resolving and extraordinarily dangerous international crisis. Waldheim rightly got a lot of credit for this performance. Even Henry Kissinger was impressed. After this episode, Waldheim appointed me to Bunche’s old position as Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs, a post that in the normal course of affairs would have been filled by an American political appointee. I greatly appreciated this mark of confidence.

A look back at some of the highlights of the career of Kurt Waldheim, the fourth Secretary-General of the United Nations.

Waldheim worried a great deal about his “image,” as he called it, but his efforts to tackle this problem often made things worse. He was too anxious to get credit and tended to be too accessible to the media, who become bored with the clichés and bland, non-committal statements which are often all the UN Secretary-General is able to say publicly. Because the international position of the Secretary-General imposes strict limits on what he can say to the media, mystery and aloofness, as practiced by Dag Hammarskjold, are often the Secretary-General's best approach. In trying to convince him of this, I once told Waldheim that if the Loch Ness Monster came ashore and gave a press conference, it would never be heard of again, but I don't think he got the point.

15 December 1955 – Kurt Waldheim’s exposure to the United Nations began early, alongside Austria’s admission process to the world body, which culminated in its gaining membership on 14 December 1955, six months after the country regained its full independence in the wake of World War II. It became the UN’s 70th member. Following his army service in the war, Waldheim joined the Austrian diplomatic service in 1945, and after serving in Paris and Vienna, he was appointed Permanent Observer for Austria to the UN, before, later that year, becoming head of the Austrian Mission when his country was admitted to the Organization. In this photo, Waldheim is shown at his desk before a plenary meeting at the General Assembly Hall at UN Headquarters in New York the day after Austria’s admission. UN Photo

08 October 1970 – From 1956 to 1964, Mr. Waldheim continued serving with the Austrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, including as ambassador to Canada and within the ministry in Vienna, before his appointment as Permanent Representative of Austria to the UN, and serving in this role between 1964 to 1968. During that period, he was Chairman of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space and was elected President of the first UN Conference on the Exploration and Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. Subsequently, from 1968 to 1970, he was Austria’s Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs. In mid-1970, he again became his country’s Permanent Representative to the UN. Shown here is Ambassador Waldheim presenting his credentials to Secretary-General U Thant at UN Headquarters. UN Photo

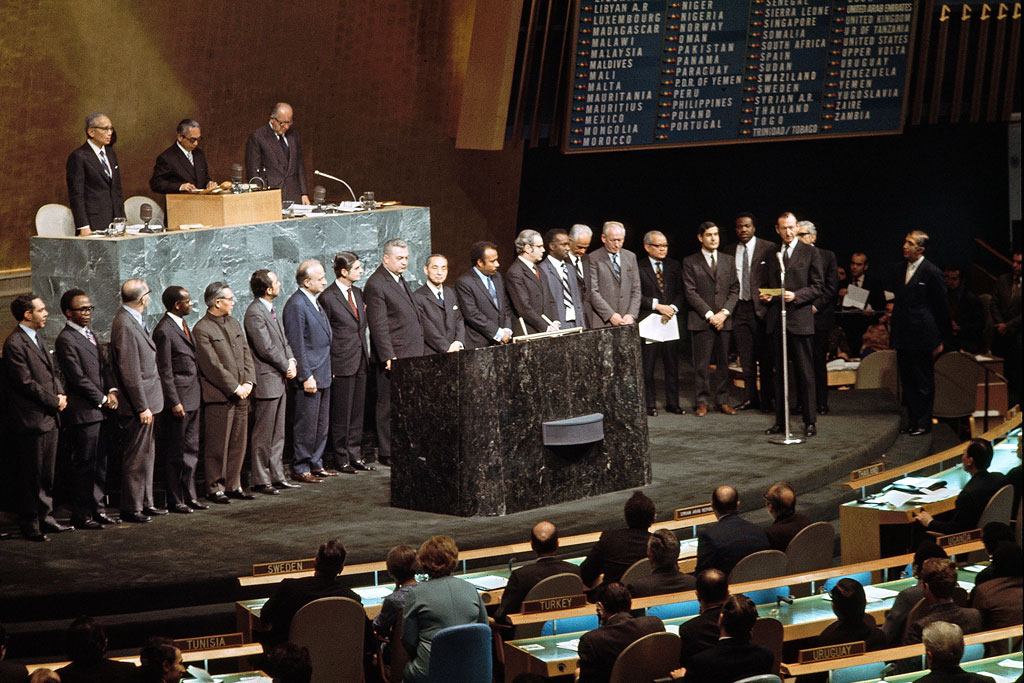

22 December 1971 – The UN General Assembly concluded its 26th session with the appointment – by acclamation – of Ambassador Waldheim as the UN’s fourth Secretary-General, with a five-year term beginning on 1 January 1972. Shown here, Amb. Waldheim (at microphone) takes the oath of office. UN Photo

18 May 1972 – During his first three years as Secretary-General, Mr. Waldheim made it a practice to visit areas of special concern to the United Nations. This included visiting, soon after he began his term, South Africa and Namibia in order to help find a satisfactory solution for the problem of Namibia, which was occupied then by South Africa. Shown here, some two months after he visited both countries, Secretary-General Waldheim meets with South African government officials, including the country’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, on the issue of Namibia, in the last meeting of a round of talks at UN Headquarters. UN Photo

06 June 1972 – Long-simmering tensions between Greek and Turkish Cypriots on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus erupted into intercommunal violence, which led to the involvement of the United Nations – including the deployment of UN peacekeepers. Secretary-General Waldheim visited the island on several occasions. Shown here, he is in discussions with Cypriot President Archbishop Makarios in the city of Nicosia, during a visit to the island, Turkey and Greece. UN Photo

13 August 1972 – The issue of China’s representation at the United Nations had been an ongoing one for many years, with the UN General Assembly taking up the issue in 1971. This culminated in the Assembly recognizing the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as the legitimate representative of China to the world body in October 1971 in a resolution with 76 votes in favour, 35 against and with 17 abstentions. Shown here, during a visit to China, Secretary-General Waldheim is greeted by Premier Chou En-lai at the People's Hall in the capital city of Peking (now known as Beijing). UN Photo

12 February 1973 – Early 1973 saw Secretary-General Waldheim on a five-nation trip to south-east Asia, which included India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Thailand and Japan. Shown here, Thailand’s King Bhumibol Adulyadej and the Queen receive the UN chief and his wife at the Chitra Lada Palace in the capital city of Bangkok. UN Photo

20 June 1973 – Hailing from the region of Catalonia in Spain, Pablo Casals was a world-renowned international humanist, cellist, conductor and composer who actively supported the United Nations in its activities – so much so, that he was awarded the UN Peace Medal for his efforts. At the award’s presentation, he said: “This is the greatest honour of my life. Peace has always been my greatest concern… And the first United Nations were in my country. At that time – the 11th Century – there was a meeting in Toluges – now France – to talk about peace, because in that epoch Catalans were already against, against war. That is why the United Nations, which works solely towards the peace ideal, is in my heart, because anything to do with peace goes straight to my heart.” Shown here, Maestro Casals and Secretary-General Waldheim, and their wives, enjoy a moment together following a luncheon at UN Headquarters in the artist’s honour. UN Photo

29 August 1973 – In the early 1970s, the Middle East was troubled by a range of events that included conflicts and coups, as well as ongoing inter-communal tensions, which involved UN efforts to bring stability. In mid-1973, Secretary-General Waldheim paid an eight-day visit to the region, where he held wide-ranging talks with the leaders of Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Egypt and Jordan. Shown here, accompanied by Brian Urquhart (to Mr. Waldheim’s immediate right), then serving as Assistant Secretary-General for Special Political Affairs, the UN chief meets with Lebanon’s Foreign Affairs Minister, Fouad Naffah, in the capital city, Beirut. Less than two years later, civil war broke out in the Middle Eastern country. UN Photo

30 August 1973 – In 1967, Israel had fought a war with several neighbouring countries, and tensions were still high amongst them in subsequent years. On his eight-day visit to the region, Secretary-General Waldheim met with Israel’s Prime Minister Golda Meir and Foreign Minister Abba Eban in Jerusalem, as shown here. To the right of the UN chief is Brian Urquhart. UN Photo

26 September 1973 – The role of the UN Security Council in international affairs is an important one. Under the UN Charter, it has primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security, taking the lead in determining the existence of a threat to the peace or act of aggression. Shown here, ahead of a dinner held in New York City for the heads of delegations of the Council’s five permanent members, Secretary-General Waldheim (third from left) poses for a photo with (from left): the Soviet Union’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, A.A. Gromyko; France’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, Michel Jobert; the United States’ Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger; the United Kingdom’s Secretary of State and Commonwealth Affairs, Sir Alec Douglas-Home; and the Permanent Representative of China to the UN, Huang Hua. UN Photo

08 November 1973 – The deployment of UN peacekeepers and military observers to the Middle East in the 1970s was not without risk, and sometimes fatally so. Shown here, Secretary-General Waldheim during a memorial ceremony held at UN Headquarters in tribute to three UN military observers who lost their lives while carrying out their duties during hostilities in the region: Captain Georges Banse of the French Army, Captain Carlo R. Oliviere of the Italian Army, and Captain Didridk B. Tjorswaag of the Royal Norwegian Air Force. UN Photo

21 February 1974 – In early 1974, Secretary-General Waldheim visited 14 West African countries, including six drought-stricken nations in the Sahel, and in which he saw first-hand the impact of the drought. In what was then known as the Upper Volta (and now known as Burkina Faso), he issued an urgent appeal for more aid, especially food and money, for the Sahel. Shown here, in the capital city of Ouagadougou, the UN chief talks to local residents about the distribution of relief supplies in Gorom-Gorom, one of the worst-affected areas. UN Photo

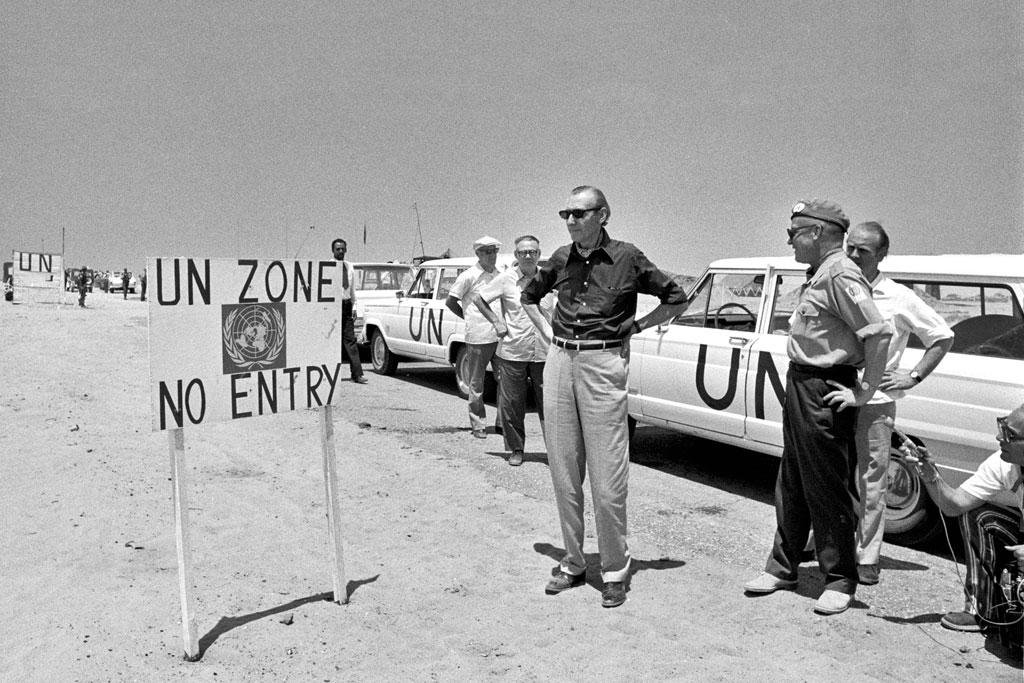

07 June 1974 – Ongoing conflicts and tensions in the Middle East continued to draw Secretary-General Waldheim’s attention in the early 1970s, with more visits to the region for talks with government officials in Lebanon, Syria, Israel, Jordan and Egypt. Shown here, the UN chief during an inspection of a peacekeeping unit of the UN Emergency Force (UNEF) in the Suez Canal Zone and the Sinai. UN Photo

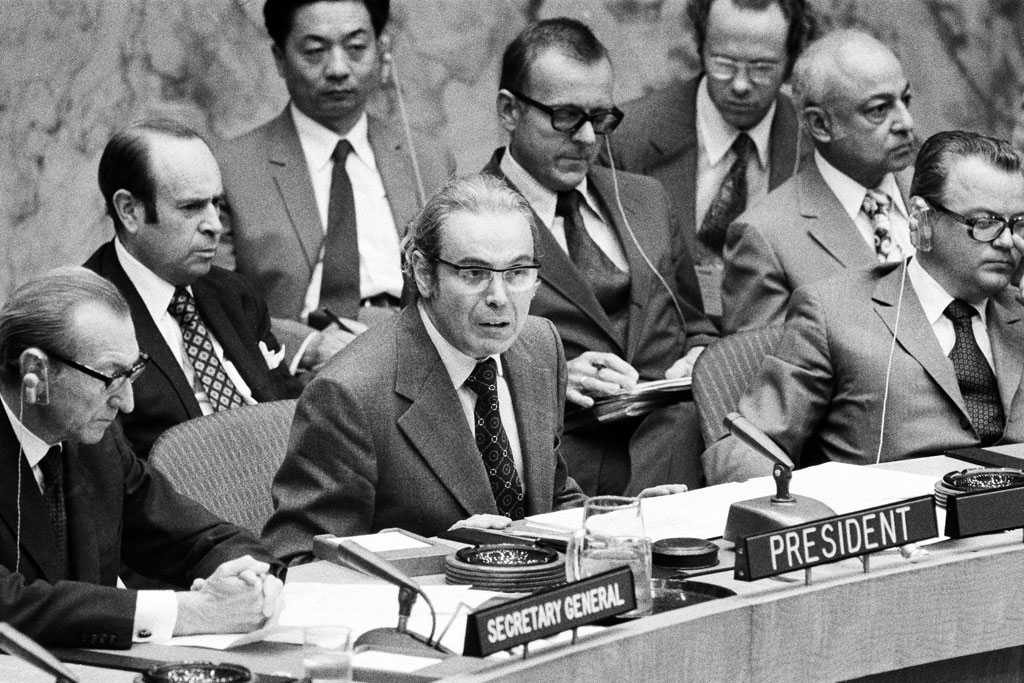

20 July 1974 – The situation in Cyprus worsened in July 1974. A coup staged by rebel forces against the Government of Archbishop Makarios on 15 July was followed by a Turkish military invasion on 20 July. Subsequently, the UN Security Council met and unanimously called on all parties to the fighting to cease all firing and requested all States to exercise the utmost restraint and to refrain from any action which might further aggravate the situation. Shown here, Secretary-General Waldheim at that meeting, seated next to the Council’s President for the month, the Permanent Representative of Peru to the UN, Ambassador Javier Perez de Cuellar – who, several years later, was to succeed Mr. Waldheim as UN chief. UN Photo

Bringing together a number a groups seeking a Palestinian state, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was established in 1964, under the auspices of the League of Arab States. One of those groups, Fatah, was led by Yasir Arafat, who eventually became the chairman of the PLO’s Executive Committee – and, over the years, he became closely identified with the Palestinian cause in international affairs as well as by the general public. Mr. Arafat was invited to address a General Assembly debate on the question of Palestine. Shown here, Secretary-General Waldheim and Mr. Arafat in conversation just prior to the opening of the Assembly’s debate at UN Headquarters. UN Photo

7 March 1975 – Over the decades, the issue of discrimination against women had been garnering more attention throughout the world – and, internally, the United Nations was not excluded from this shift. Shown here, the Chairperson of the Ad Hoc Group on Equality for Women and the Chairman of the Staff Council present a petition to Secretary-General Waldheim requesting an affirmative programme of action to end discrimination against women in the UN system. It had been signed by over 2,700 staff members. UN Photo

18 November 1975 – Henry Kissinger is a world-renown diplomat and political scientist who served as US Secretary of State in the 1970s, and is still sought after for his views on world affairs. In his role as the US’ top diplomat, he was often seen as UN Headquarters in New York. Shown here, Mr. Kissinger addresses the media at UN Headquarters, alongside Secretary-General Waldheim, following a meeting between the two men. UN Photo

23 November 1975 – Sectarian violence in Lebanon early 1975 led to a full-blown civil war that involved neighbouring countries and UN peacekeepers, and which only ended in 1990. One of the neighbouring countries drawn into the conflict was Syria, which intervened militarily in 1976. Shown here, Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim is seen in a meeting with the President of Syria, Hafez al-Assad, at the Presidential Palace in the Syrian capital of Damascus. UN Photo

31 May 1976 – Although the UN General Assembly had already urged its members to address urbanization issues, it was only in the 1970s that tangible actions were taken to deal with the rapid and often uncontrolled growth of cities. With growing awareness of the impact of urbanization, the first international UN conference – Habitat I – to fully recognize the challenge of urbanization and deal with the problems of rapid, unplanned urban growth was held in 1976 in the Canadian city of Vancouver, and it led to the creation, in December 1977, of the precursors of what was eventually to be known as UN-Habitat, the UN agency charged with dealing with the issue. Shown here, the Prime Minister of Canada, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, is greeted on his arrival at the gathering by Secretary-General Waldheim. UN Photo

12 February 1977 – Dealing with the media has been a constant part of the work of Secretaries-General, both at UN Headquarters and while travelling abroad. Shown here, Secretary-General Waldheim addresses the media in front of the terminal at the Nicosia International Airport which, at that time, had not been in use since the war of July-August 1974. UN Photo

17 March 1977 – The President of the United States for Secretary-General Waldheim’s second term was Jimmy Carter. At a working luncheon between the two men in early 1977 at the White House, soon after he took office, the US President said: “I look forward to a long and continuing and, hopefully, mutually successful effort between our country and the United Nations to bring about peace in the world and to protect human rights and to meet those needs that are so vivid in our world today.” Shown here, Secretary-General Waldheim conversing with President Carter during the latter’s visit to UN Headquarters, during which he also addressed an informal gathering of UN Member States in the General Assembly Hall. UN Photo

18 April 1978 – Given the war raging in Lebanon, the UN Security Council passed a resolution in March 1978 creating the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL). Initially, it was tasked with confirming Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon, restoring international peace and security and assisting the Lebanese Government in restoring its effective authority in the area. Secretary-General Waldheim paid a brief visit to the region to discuss the implementation of the resolution with those concerned, such as governments of the region as well as to meet with UN peacekeepers on the ground. Shown here, accompanied by UNIFIL’s Force Commander, Major-General Emmanuel Erskine (standing immediately behind Mr. Waldheim) of Ghana, the UN chief visits an eastern area outpost manned by Norwegian peacekeepers. UN Photo

16 May 1978 – Since its early days, artists have helped play a role in highlighting the values and principles embodied by the United Nations. Shown here, Secretary-General Waldheim presents UN Peace Medals to Australian musical group known as the “Bee Gees” at a ceremony held at UN Headquarters. The group was producing a record entitled “Music for UNICEF,” with the proceeds being donated to the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) for the “Year of the Child – 1979” celebrations, which also included the group staging a concert in the General Assembly Hall in January the following year. UN Photo

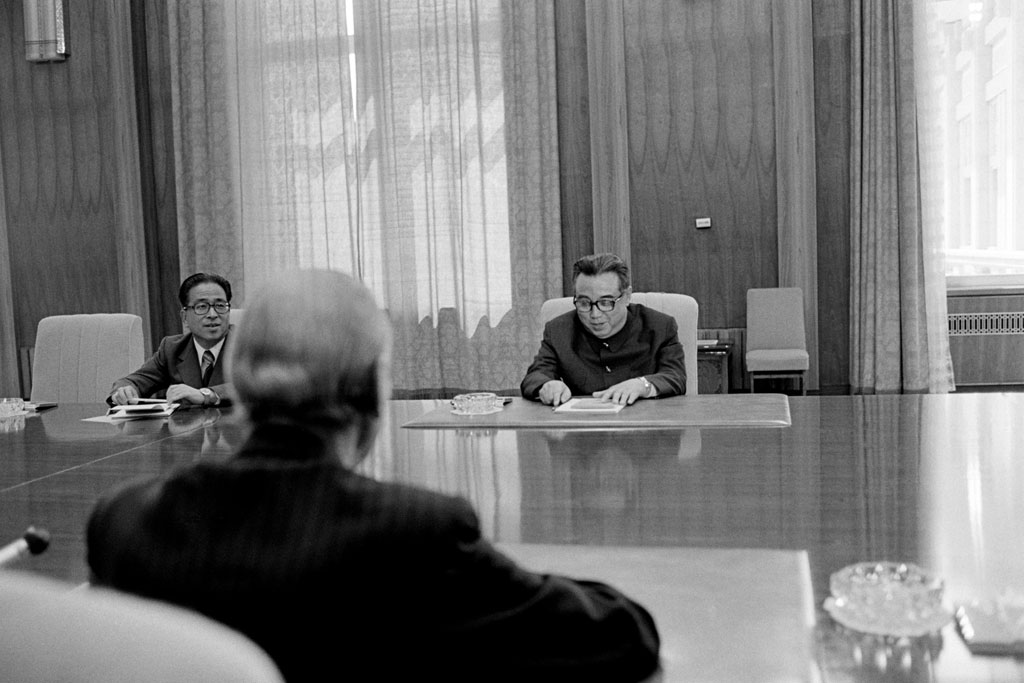

03 May 1979 – The issue of dialogue on between the two countries on the Korean Peninsula had been an ongoing one since an armistice halted the fighting in 1953. The UN was involved in this efforts over the years, including with Secretary-General Waldheim becoming the first UN chief to visit the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. Shown here, Secretary-General Waldheim (back to the camera) meets with President Kim Il Sung during a visit to the capital city, Pyongyang. UN Photo

26 September 1979 – The Khmer Rouge regime had control of Cambodia (which it renamed Kampuchea) between 1975 and early 1979, after which it was overthrown by neighbouring Vietnam, and which also installed a new government – made up of officials who had previously been part of the Khmer Rouge. As they withdrew, the defeated Khmer Rouge forces destroyed food crops which led to a dire humanitarian situation for many in the country. Shown here, Secretary-General Waldheim in a meeting with the Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister of Democratic Kampuchea, Ieng Sary (centre), at UN Headquarters in New York. Near the end of his term, the UN chief and former Beatles musician Paul McCartney helped organize a series of concerts to aid the people of the south-east Asian nation. UN Photo

21 January 1980 – In late 1966, the UN General Assembly established the UN Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), with the new UN agency’s aim centred on promoting and accelerating the industrialization of developing countries. Over the years, UNIDO’s role has been further refined so that it now focusses on promoting industrial development for poverty reduction, inclusive globalization and environmental sustainability. Shown here, Secretary-General Waldheim greets Prime Minister Indira Gandhi at the inauguration ceremony for the Third UNIDO General Conference, held in the Indian capital of New Delhi. UN Photo

15 December 1981 – Secretary-General Waldheim’s second term at the helm of the world body was due to finish at the end of 1981. He sought an unprecedented third term as Secretary-General, but was unsuccessful in the attempt. Shown here, at the podium of the General Assembly Hall at UN Headquarters, Secretary-General Waldheim embraces his successor, Javier Perez de Cuellar of Peru, to the applause of other representatives of UN Member States. UN Photo

15 June 2007 – Kurt Waldheim passed away at the age of 88 in Vienna, the capital city of Austria, for which he had also served, subsequent to his UN career, as president from 1986 to 1992. Shown here, the UN General Assembly observes a minute of silence in tribute to the memory of the former Secretary-General, at UN Headquarters in New York. In his remarks at the event, the then-UN chief, Ban Ki-moon, said: “Kurt Waldheim's 10 years at the helm covered a deeply challenging time in the world and in the life of our Organization. He needed to deploy every diplomatic and political skill acquired over a long career, including as Austria's Permanent Representative to the United Nations and Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs. He led the Organization with prudence, perseverance, and precision… Almost two decades later, when I served as my country's Ambassador to Vienna, I came to know Kurt Waldheim personally, after his retirement from his public life. He was a man who had lived history. The world had changed yet more, in even more unimaginable ways.” UN Photo

Waldheim did not have intellectual interests, and I don’t remember ever seeing him reading a book for pleasure. He was wedded to official life, even to its endless official meals, and he was determined not to be separated from it. In 1976, his first term as Secretary-General was coming to an end, and he desperately wanted to be re-elected. I told him that second terms had not proved happy for his predecessors, but if he wanted one, the best way to get it was simply to get on with his work. This was the last thing he wanted to hear, so he did not include me in his frantic re-election campaign. The prospect of running for office brought out the worst in Waldheim. He seemed to become a man without real substance, quality of character, and swept along by an insatiable thirst for public office. Although it was quite unnecessary, he wooed governments, ambassadors, and the press blatantly and shamelessly. And he was re-elected.

The last five years with Waldheim were perfectly tolerable as far as I was concerned. I think he really came to care about the United Nations as an institution, as well as about the problems we're trying to deal with. He certainly did well enough for all governments, except China, to wish to keep him on for a third term. Waldheim's efforts to secure a third term far exceeded his earlier campaign. As he buttonholed, cajoled and wheedled everyone in sight, he became a figure of farce. Ministers and diplomats scurried nervously along the corridors, dreading the familiar grasp of the Secretary-General’s hand on their elbow. He was defeated by the Chinese veto.

As the world was to discover later, Waldheim had a flexible way with the truth. When taken by surprise he was apt to make off-the-cuff statements, and when they caused uproar, he would try to deny or alter them. Once in Jerusalem, when he had, after a very long day, publicly referred to that city as the capital of Israel, I persuaded him, with some difficulty, to say simply that he had misspoken, and the story died instantly, but that was an exception. He told a journalist with a tape recorder at the Cairo airport that the Israeli raid to release the passengers of a hijacked aircraft at Entebbe was an infringement of Ugandan sovereignty, as indeed it was. When there was an angry reaction in the United States, he tried for days to maintain that he had been misquoted, thus blowing up a trivial incident into a major story. He would spend hours editing the transcripts of his press conferences and was irritated when I pointed out that one hundred or so correspondents, many with tape recorders, had already heard what he had actually said. Even so, I never suspected that he had also edited the story of his military career.

Waldheim had never been a member of the Nazi Party, but during the war he had served, as had most young Austrians, in the German army. It is hard to understand why he should have lied about the last three years of his military service, as an intelligence officer in the Balkans, claiming that he had been wounded on the Russian front and returned to civilian life in early 1942. United States intelligence had interrogated him extensively about the Balkans in 1945, so the United States had always had the true story of his military career in its files, as had other governments, but they had failed to recall this at the time of his election as Secretary-General. When the story of his misrepresentations came out in 1986 when Waldheim was President of Austria, it was regarded, especially in the United States, which had voted three times for him as Secretary-General, as a scandal and as highly damaging reflection on the United Nations.

Having worked closely with Waldheim and publicly defended him on the basis of his false version of his military career, I felt betrayed and angry, and I said so in my memoirs. In 1995, when I was visiting Vienna, I received word that the former president urgently wanted to meet with me. We met in a gilded room in the Hofburg. Waldheim began to berate me for “unfriendliness,” and I replied that in my whole professional career he was the only person I had worked with who had deliberately lied to me on a matter of importance. It was a sad and unsatisfactory conversation.