Can plants and trees change the weather?

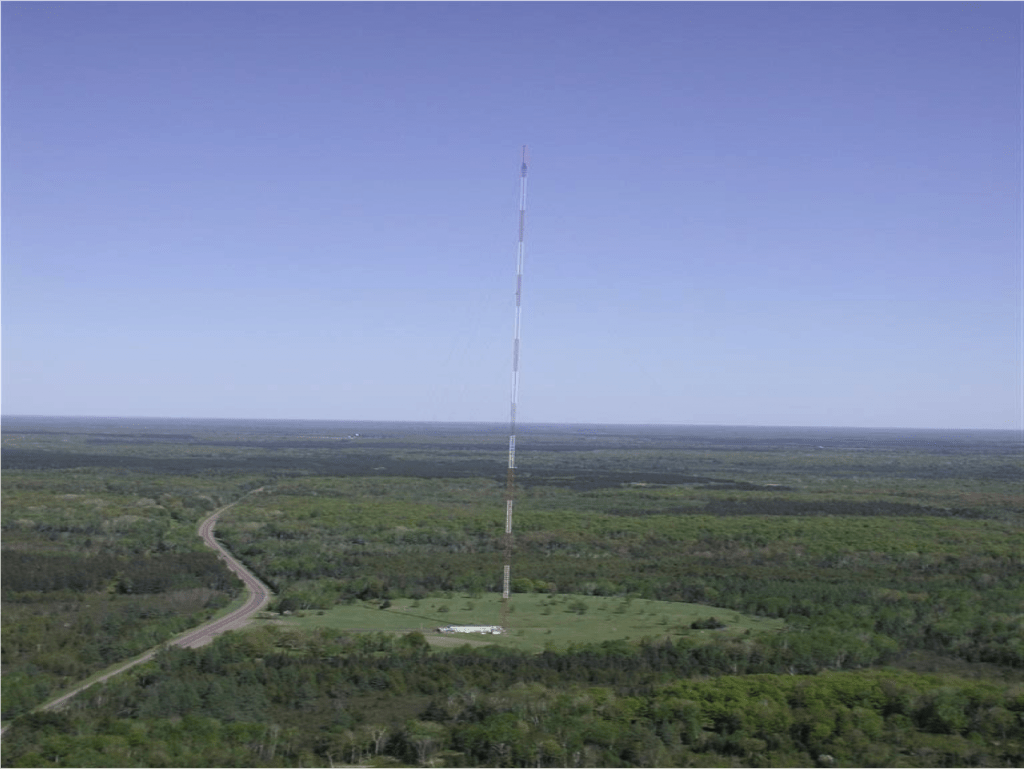

A 1,400-foot Wisconsin Educational Communications Board television tower in Park Falls, Wisconsin has for more than a decade hosted atmospheric instruments that gather data on humidity, temperature, greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane, and more. Photo by Ankur Desai, UW–Madison

By this time next year, an army of towers will be keeping watch over a plot of land in the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest of northern Wisconsin. They will be joined by a turbo-prop plane, an ultralight aircraft, a state-owned Cessna, ground-based atmospheric instruments, and a troop of students and scientists, each playing a role in helping to understand how plants and trees contribute to weather patterns on a local scale.

The project, named CHEESEHEAD19 (for Chequamegon Heterogeneous Ecosystem Energy-balance Study Enabled by a High-density Extensive Array of Detectors 2019), is headed by University of Wisconsin–Madison Professor of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences Ankur Desai and was just awarded a $1.5 million dollar grant from the National Science Foundation. An additional $1.5 million will go toward covering instrumentation required for the study.

“It may help us improve weather forecasting because it will tell us how vegetation and forest management influence the atmosphere,” says Desai, a member of the Center for Climatic Research (CCR) at the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies.

The 1,400-foot Wisconsin Educational Communications Board television tower in Park Falls is operated by University of Wisconsin–Madison Professor of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences Ankur Desai and collaborators. Photo by Ankur Desai, UW–Madison

When plants are green and growing, they absorb carbon dioxide in the process of photosynthesis, converting it into (plant) food and oxygen. They also exchange water with the soil and the air. Plants are constantly cycling carbon dioxide and water.

However, in the fall, only some plants are green and growing while others are dropping their leaves. This means the amount of carbon dioxide and water they cycle with the atmosphere becomes more variable.

Desai and his colleagues want to know whether this variability changes how heat and moisture dissipate up and down within the atmosphere and how that leads to cloud formation and the development of storms on a local scale.

“Weather and climate models are poor at getting at this because they are on a large-scale,” says Desai.

Over the course of two years, beginning in 2019, he and his research team will collect measurements in a 10-by-10 square kilometer area from a region of the country sensitive to changes in climate. For more than a decade, Desai and collaborators have operated atmospheric instruments on a 1,400-foot Wisconsin Educational Communications Board television tower in Park Falls, gathering data on humidity, temperature, greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane, and more.

But the new approach allows researchers to make measurements across both time and space like never before. In addition to the instruments on the WLEF-TV tower, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, based in Boulder, Colorado, will deploy 17 additional towers, known as flux towers, to the site. The telescoping towers reach as high as 100 feet. They allow scientists to capture data from a range of places within the study site, both geographically and with respect to the height of the atmosphere.

The twin-engine jet, a King Air managed by the University of Wyoming, will at peak times fly at 300-feet, collecting data from a region of the atmosphere not often studied. The ultralight aircraft built by UW–Madison Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences Professor Grant Petty will gather additional readings from a range of heights. Another instrument, called the Spectral Explorer, led by UW–Madison Professor of Forest and Wildlife Ecology Phil Townsend and supported by the UW2020 Initiative, will help the team gather unique vegetation data.

Ankur Desai stands in front of a 27-meter-tall flux tower in 2011. Photo: Bryce Richter

Desai says the team will also partner with schools in northern Wisconsin, like those in the Butternut School District, to involve interested middle and high school students. He will accomplish this through a collaboration on a new Ira and Inerva Reilly Baldwin Wisconsin Idea Endowment grant awarded to Rosalyn Pertzborn in the UW–Madison Office of Space Science Education and Michael Notaro, associate director of CCR.

“I think this is a relatively underserved area and we are bringing high-tech science into their backyard,” says Desai, who also plans to host a minimum of two public days in the summer and fall of each study year.

The funding will also create up to three new graduate student positions and two postdoctoral positions, in addition to supporting opportunities for UW–Madison, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee and Northland College undergraduate students. Desai is already planning to host one of his classes at the site several times next fall.

“I really see this as the Wisconsin Idea perspective,” he says. “And I’m excited about it because it includes a lot of partners and there are not a lot of places in the world where all these things can happen.”

Other project leaders include Mark Schwartz at UW–Milwaukee and Stefan Metzger at the NSF-supported National Ecological Observatory Network. Additional partners include scientists at UW–Madison’s Space Science and Engineering Center, the Kemp Natural Resources Station, the University of South Carolina, the Department of Energy Ameriflux Network Management Project, the Class Act Charter School and the United State Forest Service. All of the data from the study will also be open access.