Ever since NFL owners announced last month that they plan to fine players who protest on the field during the national anthem, critics have conducted a scavenger hunt of sorts looking for evidence that the NFL’s policy is unconstitutional.

Benjamin Sachs has written that the First Amendment, which generally applies only to governments, should apply to the NFL’s policy because the policy was the product of demands by government officials, including the president. Daniel Hemel has suggested that the First Amendment might apply to the NFL’s stadiums because of all the government subsidies used to pay for them.

But these critics may be looking for unconstitutionality in the wrong place: It’s a much clearer case that the NFL policy violates a host of state constitutions.

Before delving into these state constitutions, it’s worth looking briefly at the federal case. The First Amendment begins with “Congress shall make no law,” and while the Supreme Court has been willing to extend that language to states, it has been less willing to extend it to stadiums. For example, when protesters in Oregon wanted to distribute leaflets in a shopping mall, the court refused to apply the First Amendment to make the mall’s owners open their space to protesters as if it were the National Mall. The court has reasoned that the First Amendment prohibits a type of “law,” not a type of business policy, so it looks for activity by a state or federal official—state action—before it enforces the amendment.

State action is therefore the key to unlocking the First Amendment’s protections. And the NFL’s critics are right that it might be lurking in the tweets, speeches, and other commands from the president urging the NFL’s owners to suppress the NFL’s players. It also might be found in the tax breaks and government subsidies on which the NFL has long depended. But over the past 60 years, the Supreme Court has maintained that state action isn’t hiding under every regulation or public benefit. Banks, private universities, and many other institutions are even more heavily regulated and subsidized than the NFL. Yet few judges today would consider this enough to require these institutions to respect the Federal Constitution’s terms.

There are 50 other constitutions, though: one in every state, each of which has its own free speech clause. These state constitutions are worded differently than the federal Constitution. And state supreme courts have been more willing than the U.S. Supreme Court to subject organizations like the NFL to the same constitutional standards as governments.

Consider California—home of the Los Angeles Chargers, the Los Angeles Rams, the San Francisco 49ers, and for now at least, the Oakland Raiders. Unlike the First Amendment’s negative limit on state action, the California Constitution’s free speech clause affirmatively begins, “Every person may freely speak.” Forty years ago, the California Supreme Court interpreted this language to do what the U.S. Supreme Court would not do: Prevent the owners of a private shopping mall from kicking out protesters. Even the cautious U.S. Supreme Court enthusiastically affirmed this decision. It recognized that every state has the “sovereign right to adopt in its own Constitution individual liberties more expansive than those conferred by the Federal Constitution.”

In other words, the state-action doctrine is a feature of the U.S. Constitution, not all constitutions. And where the U.S. Constitution doesn’t apply—like in shopping malls and perhaps football stadiums—state constitutions are often the highest law of the land.

Today, many states have followed California’s lead in interpreting their own free speech clauses to prohibit private organizations from fining protesters. When the New York Jets and New York Giants open their doors in the New Jersey meadowlands this fall, they will be two of several teams playing in a state whose constitution guarantees free speech against “unreasonably restrictive or oppressive conduct on the part of private entities.” The New Jersey Supreme Court first announced this interpretation shortly before holding that Princeton University violated the state’s constitution when it fined an activist who wanted to protest on its private campus.

The constitutions in the home states of the Broncos, Eagles, Patriots, Seahawks, and Steelers similarly protect protesters from private restrictions. Although the supreme courts of these states generally tolerate reasonable rules to minimize the disruptions that protests can create, they generally strike down rules imposed to protect against a disruption unlikely to happen, to limit the content of a protest, or to avoid the backlash against an unpopular viewpoint.

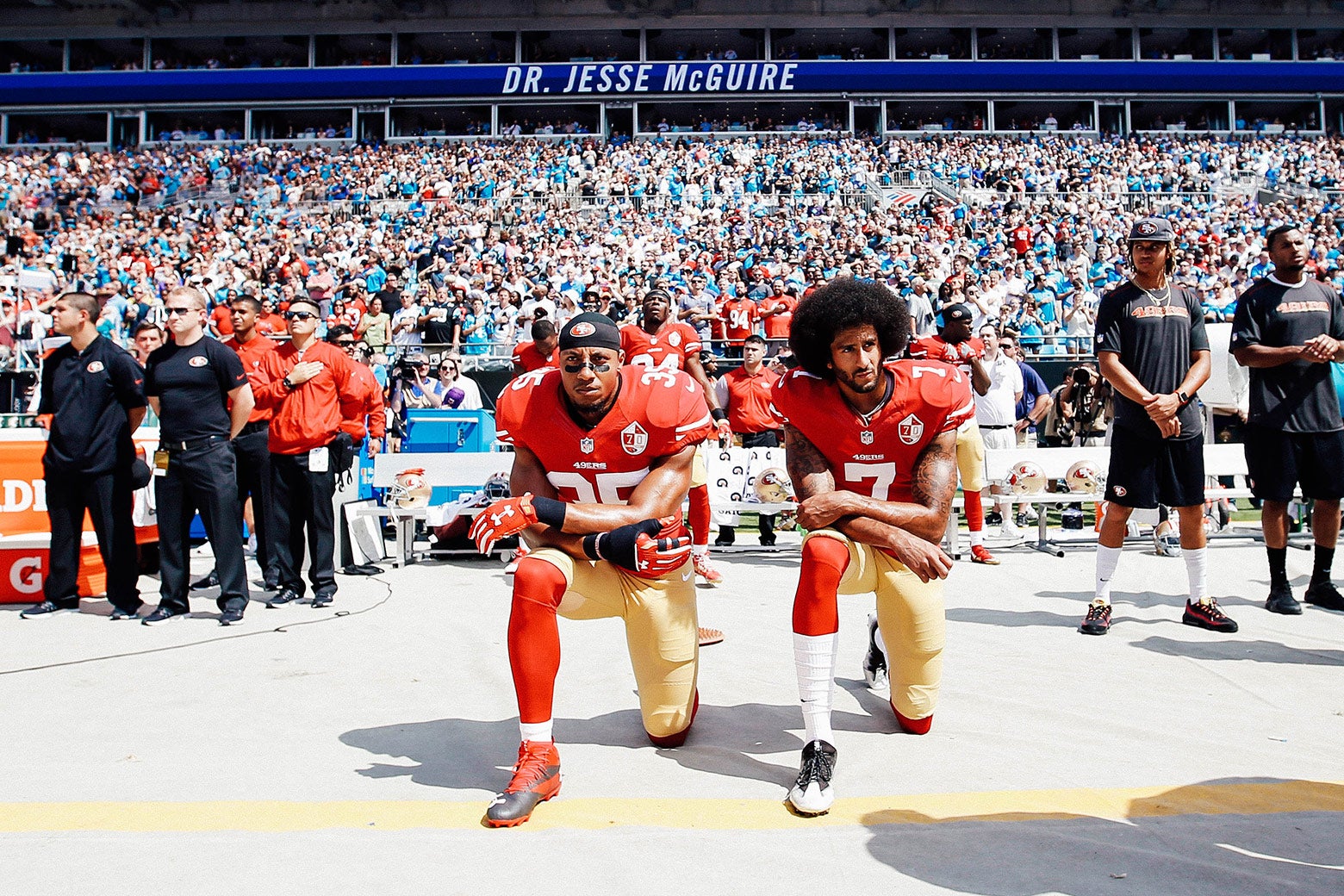

Thanks to transcripts of NFL owners’ meetings and depositions taken in Colin Kaepernick’s collusion case against the league, there is no doubt that the NFL’s policy wasn’t adopted to minimize disruptive behavior. Rather, the purpose of the policy is to restrict the political content of players’ protests merely out of fear of how fans—or the president—will respond. In this context, the NFL’s policy likely violates several state constitutions. The unconstitutionality of the policy therefore doesn’t depend on state action.

The irony of the NFL’s policy is that the American flag is worth respecting precisely because of the ideals that it’s supposed to stand for, including the ideals embodied in our state constitutions. If players take a knee this fall, it is these constitutions that will have their backs.