In Kensington, police offer drug users help instead of criminal charges

A Philadelphia police-assisted diversion program has expanded to the epicenter of the opioid crisis. The goal is to provide services to some drug users — not to make arrests.

A Philadelphia police officer moves from tent to tent telling residents of the Emerald Street encampment that it's time to go. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

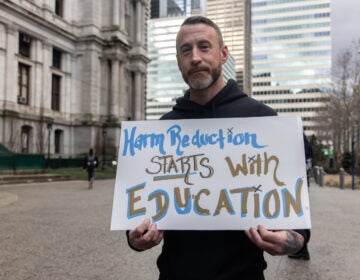

As Philadelphia works to connect more people in Kensington who struggle with opioid addiction to health care and social services, it’s getting help from an unlikely partner: the Philadelphia Police Department.

Instead of charging them with crimes, police in the 24th District in Kensington have referred some stopped for minor drug-related offenses to social workers. The program launched in March in North Philadelphia’s 22nd District and expanded to Kensington in November.

Program manager Kurt August said it gives police a better option for dealing with people who are homeless or struggling with addiction.

“The first city employee they encounter usually is a Philadelphia police officer,” August said.

When police stop someone on suspicion of low-level drug possession, shoplifting, or prostitution, the person can choose to accept help as an alternative to prosecution. The program pairs that person with a peer counselor and a service coordinator from Prevention Point Philadelphia. The help offered can include treatment, but August said the program takes a harm-reduction approach, and it doesn’t compel participants to stop using drugs.

For some people, August said, the first step might be to “help them get some food to get through the weekend, and hope that we can build enough trust that they’ll follow up with us when they’re ready to get serious help.”

Not everyone who is stopped is eligible for the program, however. Those with histories of violence or open cases against them are not allowed to participate, and a person can be diverted to the program only twice. On a third infraction, police pursue charges.

It’s not uncommon in Kensington to see someone injecting drugs in public, and many residents want police to do more to stop the disruptive behavior of people addicted to opioids.

Goal is to get people help

But Francis Bachmayer, the inspector for the police department’s East Division, said officers don’t plan to detain more drug users, even if they now have a more helpful alternative to offer them.

“Our goal is to get the person help through the appropriate provider, not make an arrest,” Bachmayer said.

The police also are offering the program to people they encounter who aren’t under arrest. Most of the participants — 33 out of 46 so far — have entered this way, through “social referrals,” August said. An additional five who wanted to be diverted after their arrests were deemed ineligible.

Bachmayer said the police department is looking at loosening restrictions on eligibility and expanding the program to the neighboring 25th District.

Police in other U.S. cities have adopted similar diversion programs in recent years, beginning in 2011 with Seattle’s Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion. August said officers received training from experts in the LEAD program model, and that the city modeled its program after one in Baltimore because of its similarities with Philadelphia.

Research in Seattle has found that participants in LEAD were 60 percent less likely to be arrested again after diversion — and more likely to find housing and employment than they were prior to their referral.

Susan Sherman, a professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health who has worked on research connected to the Baltimore program, said more evaluation of such efforts is needed, to determine whether they could also have unintended negative consequences in a community.

The programs have been criticized for giving police control over who gets access to services, Sherman said, and for “giving law enforcement too much power when they’ve caused much damage through the war on drugs, which has been waged against communities of color in urban centers.”

But, she said, diversion programs have the potential to transform how the criminal justice system responds to a public-health crisis.

“To have public defenders, public health, law enforcement, [and] prosecutors sitting together coming up with solutions is no small thing,” Sherman said. “It’s a systems change.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.