For several decades, U.S. banks reaped huge revenues from fees charged to customers who spent money they didn’t have, while also enduring a consumer backlash that tarnished their reputations.

Now the calculus is changing at a growing number of large and mid-sized banks. These firms are reducing or eliminating their reliance on overdraft fees at a time when regulatory scrutiny seems likely to increase, and as competition from lower-cost alternatives is on the rise.

The latest moves are by Ally Financial and Huntington Bancshares. Ally’s online-only bank announced Wednesday that it will permanently stop charging overdraft fees. One day earlier, Columbus, Ohio-based Huntington launched a line of credit for emergency expenses that figures to erode its overdraft fee revenue.

Those banks joined PNC Financial Services Group and Cullen/Frost Bankers, both of which announced changes earlier this year that are expected to reduce their haul from overdraft fees. The moves reflect a greater focus at banks on the financial health of customers.

“Industry is sending a clear message: it is time to move on from overdraft,” said Aaron Klein, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution.

While larger banks are getting out in front of what could be a more aggressive stance from Biden-era regulators, it could take time for smaller firms to move on, Klein said.

“For those smaller banks and maybe a few credit unions that are so intertwined in overdraft, it would be difficult for them to let the product go and still survive. It will be quite a difficult transition,” he said.

Eliminating overdraft fees ‘is good for all’

Ally’s decision to ditch overdraft fees permanently grew partly out of customer feedback that the company received during the COVID-19 pandemic, said Diane Morais, president of consumer and commercial banking at Ally Bank. In March 2020, as businesses were shuttered, Ally waived overdraft fees for 120 days.

“These are things we did last year that we learned a lot from,” Morais said in an interview.

Ally Bank, which has a large online savings franchise, collected $5 million in overdraft fees for all of last year, according to regulatory filings. That is a far smaller percentage of its deposit base than is the case at many other banks.

While the fees have not been a major revenue source for Ally, Morais noted the stress that overdraft charges can put on households. Black and Hispanic customers, in particular, have been impacted extensively by the practice, she said.

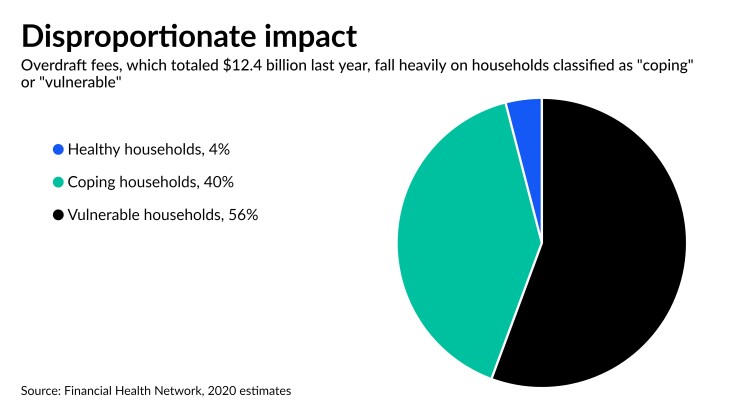

Research by the nonprofit Financial Health Network found that roughly 56% of the estimated $12.4 billion in overdraft fee revenue collected by banks last year came from households that were classified as “vulnerable,” meaning that they struggle in almost all areas of their financial lives.

Another 40% of the revenue came from “coping” households, which struggle with some aspects of their finances. While 35% of U.S. households were classified as “healthy,” they only accounted for about 4% of overdraft fee revenue.

Ally will still allow account holders to overdraw their accounts for some transactions at the bank’s discretion, Morais said. For instance, a small overdraft at the grocery store would likely still be approved, but major purchases at retail shops would not.

Morais stressed that the decision was not made in anticipation of tougher regulatory scrutiny or competition from fintechs offering low-cost accounts to pull business away from banks. And the decision to announce the change was made before a

“I’m healthily paranoid of competition old and new, but this is a decision that is independent of that,” Morais said. “We feel that the elimination of the fee is good for all.”

‘Fintech competition has made all of us better’

Huntington’s new offering is an interest- and fee-free line of credit that gives eligible customers immediate access to up to $1,000 if they enroll in automatic payback of the loan. No application is necessary, usage is reported to credit agencies and eligibility is based on consistent monthly deposit activity of $750 or more for three or more months, customers’ overdraft history and whether they keep a positive checking balance.

And once customers enroll, they can use the Standby Cash line of credit as often as they want, as long as they repay the loan within three months using automatic repayment.

“If you’re in a pinch, this is like a godsend,” Huntington Chairman and CEO Stephen Steinour said in an interview.

In explaining the bank’s decision to launch Standby Cash, he pointed to greater efficiencies in digital banking that have made such a product more economically feasible. “We’re doing more and more with digital, both for consumers and businesses, and that takes the friction and the cost out of the equation,” Steinour said.

The product will cost Huntington about $1 million a month in lost revenue, but new customers who are attracted by the line of credit will make up for “a meaningful portion” of that sum, Steinour said. The end goal for the company: product differentiation that appeals to consumers and creates not only a willingness to open accounts but also “enormous loyalty” to Huntington, Steinour said.

“There’s a short-term give-up for long-term gain, and we’re willing to make that trade-off,” he said.

Unlike Ally, Huntington has no current plans to eliminate overdraft fees entirely, but Steinour said that he views Standby Cash as an alternative for consumers who want to avoid overdraft fees. Huntington

Like Ally, Huntington pointed to events that have unfolded since the start of the pandemic in explaining its interest in exploring products that are more consumer-friendly. As the health crisis worsened, Huntington began to look for more ways to help its customers, said Bryan Carson, who leads deposit products and distribution.

Around the same time, U.S. bank regulators

“I think the industry has been challenged to solve affordable lending for a long time, and there’s just not been a good solution brought about,” Carson said. “And as we got into the pandemic, the leadership team challenged us. ... This is one of the biggest needs our customers have.”

Steinour also acknowledged the impact that fintechs are having on the U.S. consumer checking market. Neobanks such as Chime and Varo do not charge overdraft fees.

“I think the fintech competition has made all of us better,” Steinour said. “I think it has helped us innovate on the product side, and I think it’s helped us recognize the importance of user experience and design. I think banks have really benefited from the competitive dynamic and will continue to do so.”

‘Only a first step’

While Huntington said that anticipated policy changes on overdraft fees from the Biden administration did not factor into its decision-making, outside observers said that they believe some banks are trying to be proactive.

“The change in Washington has something perhaps to do with it, and it’s wonderful. I think it’s great that people have finally realized that overdraft fees disproportionately impact the people who can least afford to pay them,” said Melissa Gopnik, a senior vice president with the Boston-based nonprofit Commonwealth, which focuses on financial solutions for low-income Americans.

But Gopnik described the moves by Ally and Huntington as “only a first step.” Banks should also think about offering low-cost, low-minimum savings accounts to those same consumers, and perhaps even offering them gentle nudges to move money into savings when they have tax refunds arriving, she said.

“The challenge is, eliminating overdraft fees doesn’t address the reason you have those fees,” Gopnik said. “It doesn’t address the underlying financial reasons people have for incurring those fees, and you don’t want people worse off.”

The Center for Responsible Lending praised Ally’s decision as a significant change, but Rebecca Borné, a senior policy analyst at the consumer advocacy group, said that there’s work to do on the regulatory front.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, along with the Federal Reserve, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and other federal regulators each have roles to play in ending overdraft practices, she said.

“I wouldn’t want a decision by a single bank to be confused for systemic reform of a deeply broken checking account market,” Borné said Wednesday. “And I don’t think we’re going to see that kind of systemic reform until we have meaningful regulation in place.”

Meanwhile, Alex Horowitz, senior officer at the Pew Charitable Trusts, called Huntington’s new product a “major development” in the world of small-dollars loans. With Standby Cash, Huntington joins Bank of America and U.S. Bancorp in offering small-dollar loans.

“There’s a recognition that there’s a better way to serve customers than either repeated use of overdrafts or stepping outside the bank and borrowing from high-cost lenders,” Horowitz said.

The

Other banks that have recently announced steps to reduce their reliance on overdraft fee revenue have taken somewhat different approaches from both Ally and Huntington.

Pittsburgh-based PNC, which now has $560 billion of assets after completing its acquisition of BBVA USA Bancshares this week,

The $42.4 billion-asset Cullen/Frost in San Antonio