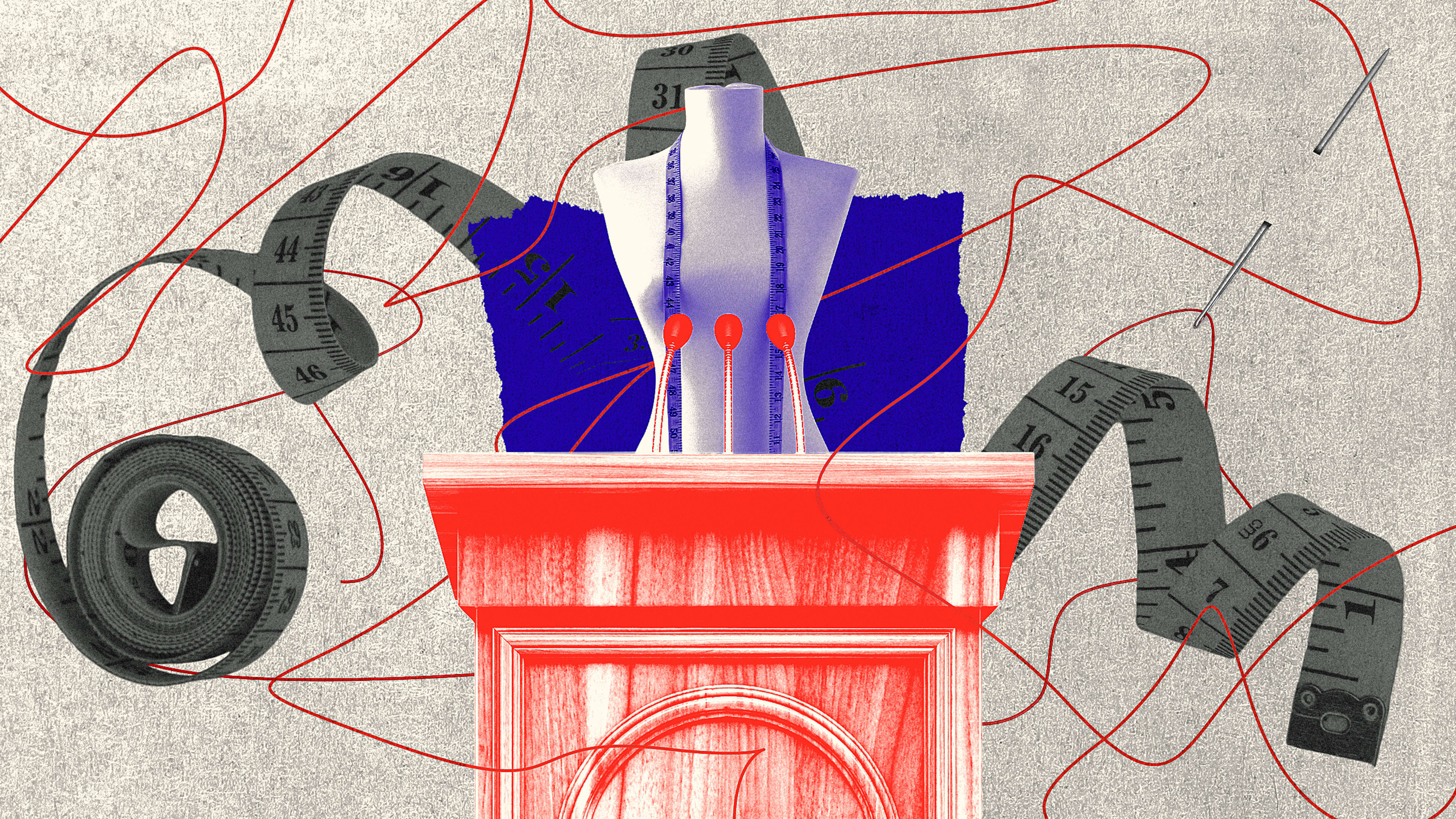

President Biden, while your administration is hard at work tackling emissions from the automobile and energy industries, there seem to be no plans to regulate fashion, which produces 10% of global carbon emissions. American fashion companies are also responsible for a panoply of human rights violations, from COVID-19 outbreaks in factories to relying on slave labor. You have an opportunity to take on this deeply problematic sector by creating a new White House position: It’s time to appoint a Fashion Czar.

The fashion industry is a $2.5 trillion beast with tentacles in every corner of the world, and yet it operates with little oversight or regulation. It employs more than 75 million people, the majority of whom are poorly paid women, who are vulnerable to abuse. This vast global supply chain means that no single country has been forced to take ownership of the terrible damage it has caused to the planet and workers. President Biden has expressed a desire to make the United States a leader in the climate fight at home and abroad. As part of this effort, he can set the agenda on how to clean up the global fashion industry, paving the way for other nations to do their part.

This is part of a series on big ideas that Biden can tackle in his first 100 days. Read the rest of the stories:

• A $15 federal minimum wage would reshape the lives of working people. Can Biden deliver?

• Can Biden do more than just undoing Trump’s anti-immigration legacy?

• Fighting AI bias needs to be a key part of Biden’s civil rights agenda

• Can Biden save public transit from the pandemic?

• Meet HARPA, the bold way Biden can jump-start health innovation

Other countries are just beginning to realize that governments have a role to play in regulating the fashion industry, but none have yet created a Ministry of Fashion. In France, Brune Poirson, one of three secretaries of state within the ministry of ecological and inclusive transition, has made it her personal mission to focus on the fashion industry’s footprint. She has championed policies such as banning brands from destroying unsold products and making microplastic filters mandatory in industrial washing machines—but fashion is not in her official job description. In Hong Kong, the government has funded a research institute to develop sustainable solutions for the industry, including building an impressive fabric recycling machine.

Biden could appoint someone who would hold the industry responsible for its environmental and human rights violations. The fashion czar could advocate for Congress to pass laws that would hold brands accountable for labor violations that take place across their supply chains and incentivize companies to come up with creative technologies that would tackle pollution. This czar could transform America into a global hub of sustainable and humane fashion, ensuring it stays a thriving part of the economy.

Americans Consume A Lot of Clothes

The United States was once a hub for textile production and apparel production. Massachusetts was famous for its footwear factories; South Carolina cotton was exported around the world. While fashion manufacturing has always been rife with human rights violations, they were easier for the government to track when they were at home. In the 1990s, when free trade agreements made it cheaper to manufacture overseas, it was far easier for companies to distance themselves from the exploitation of workers. These days, more than 95% of clothes sold in the country are made by female workers in developing countries, many of whom are subject to sexual harassment and terrible working conditions. Over the past two decades, there’s been an effort to bring garment districts back to New York and Los Angeles, but these factories have been rife with abuse as well: The U.S.-based workforce is largely made up of many undocumented workers, many of whom are paid less than minimum wage and labor under unsafe conditions, most recently exposing them to COVID-19 outbreaks.

Fashion’s complex global supply chain is part of the reason that it has such a problematic carbon footprint. When governments tackle the climate crisis, they often talk about things such as shifting to renewable energy and electric vehicles, and yet the fashion industry emits 10% of the world’s carbon. That’s because the process of extracting raw materials and then transporting them around the world is enormously carbon-intensive. A $15 T-shirt you might pick up at Target or Old Navy is likely made from cotton picked in India blended with oil-based polyester made in China. The bolt of fabric will be shipped to a low-wage factory in Asia—perhaps Indonesia or Bangladesh—and once the garment is cut and sewn, it will be shipped to the United States. All of this is aggravated by the fact that clothes are now sold so cheaply, consumers have an insatiable demand for them: More than 100 billion garments are churned out annually, and that figure is growing.

Even though the United States is no longer where most of the world’s clothes are made, we are still responsible for our part in the fashion ecosystem. For one thing, some of the world’s largest fashion brands are headquartered here—we’re also the breeding ground for the next wave of fashion labels with innovative new business models and materials. But all of these companies rely on foreign manufacturing. And perhaps more importantly, American consumers have huge spending power: Each of us spends an average of $1,883 on clothes and shoes every year, amounting to $380 billion in total spending, or 15% of the global market. That translates to about 68 garments annually, by some estimates.

Our enormous consumption means that we create a lot of fashion waste. After we’re tired of an outfit—which can happen in as few as seven wears—we throw it out. Since there is currently no way to recycle fabric the way we recycle paper or aluminum, this means that all of our clothes end up in our waste streams. More than 60% of clothes are made from plastic, which doesn’t decompose. This means that these garments will stay in our landfills for hundreds of years, or get swept into our waterways, where they will break into tiny pieces that will poison marine life—and ultimately humans.

What A Fashion Czar Would Do

So what can the Fashion Czar do about this deeply problematic industry? A great deal.

Much like the Biden administration’s climate czars and COVID-19 czar, the fashion czar would be a cabinet-level appointment. This person would be responsible for championing the White House’s agenda in discussions with Congress as well as federal agencies, specifically the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Labor. Ultimately, the czar would be tasked with pursuing regulation and persuading Congress to pass laws that curb the industry’s negative impact on the environment and workers, while encouraging businesses to come up with innovative solutions that tackle these problems.

The czar could set up a task force made up of scientists and business leaders to quickly identify top priorities and the best way to tackle them. Technology will play a critical role in reducing waste. A branch of the Hong Kong government has already developed a machine that can recycle fabric blends into new fabrics, a process that could reduce the industry’s carbon footprint, because recycling fiber is far less carbon-intensive than creating it from raw materials. Other startups are developing biodegradable fibers that can replace polyester and nylon.

Right now, these are all small-scale efforts, but the government could help move them along quickly through projects like the White House Demo Day that connected companies, colleges, and individuals with great ideas to VC and crowdfunding firms. One immediate goal of this innovation would be to keep clothes out of landfills by making fabric recycling the norm and widely available throughout the country’s curbside recycling infrastructure. We should be able to recycle an old T-shirt the way we currently recycle a Coke can.

And the government could help improve labor conditions in the fashion industry, both at home and around the world. The Biden administration has already expressed a desire to crack down on human rights abuses in China, where 1.5 million Uighur Muslims are detained in forced labor camps that supply brands from around the world. (A government report puts Nike and Patagonia among the brands suspected of using forced labor.) A bill sponsored by Florida senator Marco Rubio and passed into law last summer requires U.S. companies to provide quarterly reports of operations in the Xinjiang region, where this forced labor occurs. But why stop there? The government can and should demand that American fashion labels account for conditions throughout their supply chains, including third-party factories.

And just as urgently, the fashion czar should address human rights abuses in American garment factories, where workers are currently getting sick with COVID-19, even as they manufacture PPE for the rest of us. While there are laws meant to ensure that factory workers have safe working conditions and a minimum wage, they are often not enforced, as journalists and academic researchers have documented again and again. The government could pass laws making fashion brands responsible for any wage theft and other violations experienced by workers in their supply chains. In California, state senator Maria Elena Durazo tried to pass a bill that outlawed the practice of paying garment workers per piece produced rather than by the hour, which makes it easy for companies to underpay workers. However, it died in September 2020 because it failed to come up for a vote before the legislative session’s deadline. If the Biden administration put its weight behind this kind of legislation, it could go a long way toward protecting workers.

The United States could become the leader in a global movement toward a more sustainable fashion industry. But to get there, we need to take seriously the threat that this industry poses to our planet and human life. The new fashion czar could lead the way.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.