Yves here. The press has been featuring high level recaps of the latest IPCC report on climate change…and they are high level of necessity, since the documents weigh in at 14,000 pages.

Bob Henson of Wunderderground fame goes into key data in his overview.

By Bob Henson. Originally published at Yale Climate Connections

Torching a landscape already desiccated by record heat and severe drought, the McKay Creek Fire threatens the town of Lytton, British Columbia, on June 30, 2021, the day after Lytton recorded Canada’s all-time highest temperature of 49.6°C (121°F). Hours after this imagery was collected, most of Lytton was destroyed by fire. (Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory)

A hellish northern summer laced with deadly heat waves, perilous floods, and massive wildfires may be just a preview of coming attractions, according to a blockbuster new assessment from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The assessment lays out how the planet’s air, oceans, and ice are pushing relentlessly into new territory.

Eight years of research from more than 14,000 papers have been telescoped into the exhaustive new report, part of the sixth comprehensive assessment in the IPCC’s 33-year history.

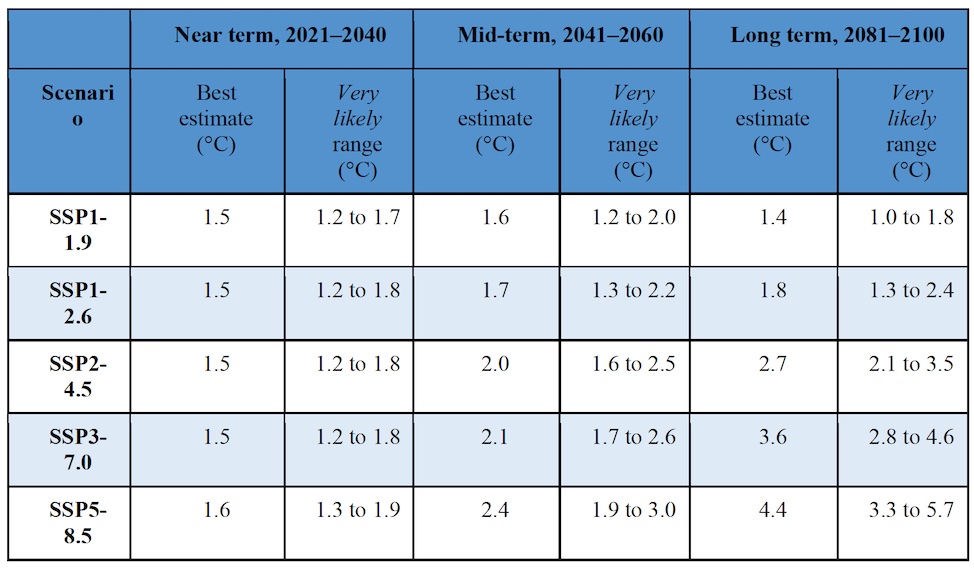

The report finds that Earth is on the doorstep of the much-discussed 1.5°C threshold, more likely than not to be reached by 2040. The hazards of compound impacts – such as heat and drought together – have risen to new prominence since the last assessment, and the risks of cataclysmic tipping points continue to loom.

“Unless there are immediate, rapid, and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, limiting warming to 1.5°C will be beyond reach,” said Ko Barrett, senior advisor for climate for NOAA’s Office of Atmospheric Research and one of three IPCC vice-chairs, in a press briefing on Sunday, August 8.

On Monday, the panel released the Summary for Policymakers from Working Group I, devoted to the foundational physical science of climate change. Still to come over the next few months are new assessments from Working Group II (impacts, adaptation and vulnerability) and Working Group III (mitigation, or how to avert further climate change).

IPCC is one of the most expansive science review efforts in global history. Rather than conducting its own research, the panel evaluates studies by thousands of scientists from around the world. The idea is to gauge which findings represent the most solid guidance needed for policymakers, governments, businesses, and individuals to address climate change.

The most startling conclusions from IPCC tend to be contextual: how a range of recent studies fit together into a coherent picture. Like a jigsaw puzzle, the result of a complete IPCC assessment can be more illuminating than any single piece. The newly appreciated threats from compound impacts are a prime example.

Notably, the IPCC has stepped up its graphics game in the new report, which has a number of crisp, striking visualizations (see below).

Hottest in Two Millennia

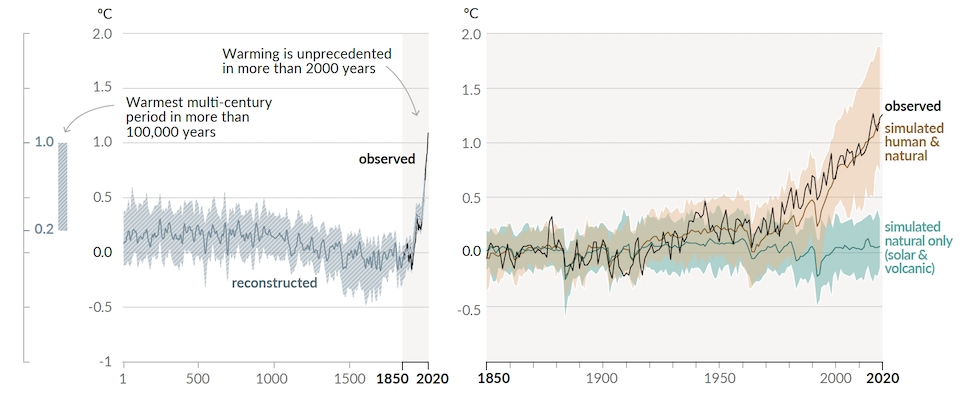

In an arresting new look at observed global temperature, IPCC has updated its famous “hockey stick” graphic, so named because of the sharp upward bend since 1850 as compared to past centuries. Featured in the IPCC’s third full assessment report in 2001, the hockey stick became a flashpoint of contention in the world of climate science denial; however, numerous studies have since borne out the concept’s validity.

The long end of the hockey stick now extends back to the year 1 AD, and warming since 2000 has only lengthened the uptick at the end (see below left).

Global temperature has risen more since 1970 than in any half century going back to (and before) the days of Caesar, Cleopatra, and Christ. To arrive at a multicentury period warmer than 1850-2020, one has to go back to before the last ice age, more than 100,000 years ago.

The new report also updates one of the most powerful pieces of evidence for human-produced climate change: a comparison of model portrayals of global temperature since 1850 from two sets of models, one including and one excluding the last 170 years of emissions from fossil fuel burning (see below right). Without these human-produced greenhouse gases, the warming since 1850 simply doesn’t happen.

How Much Warming Ahead?

As always, the IPCC makes clear that the amount of climate change ahead depends crucially on if and how quickly the world ramps down greenhouse gas emissions. Many impacts, including the most fearsome weather extremes, are expected to increase roughly in proportion with emissions, and that’s not even counting the most fraught tipping points (see below).

In the blunt words of the new report: “With every additional increment of global warming, changes in extremes continue to become larger.”

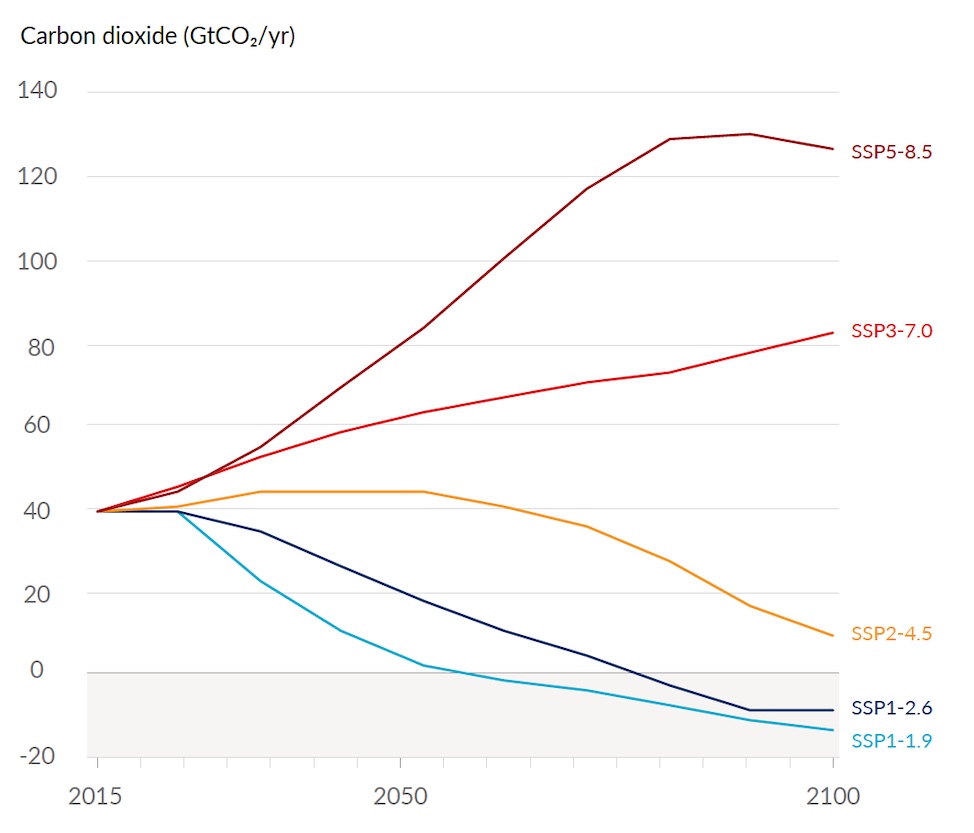

To see where the planet may be headed, the new assessment draws on a new set of five emission scenarios, called shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs). These vary a bit from the previous representative concentration pathways (RCPs), but together they still span a wide range, from a business-as-usual track (SSP5-8.5) to negative emissions by the 2050s (SSP1-1.9).

The SSP1-1.9 scenario is a newly aggressive track prompted by the 2015 Paris Agreement’s call to keep global warming well below 2°C over preindustrial temperature, and preferably no more than 1.5°C. In the IPCC’s last assessment, “there was not a single scenario that was compatible with limiting warming to 1.5°C, because we didn’t really have that objective before the Paris Agreement,” said Maisa Rojas Corradi of the University of Chile, a coordinating lead author for Chapter 1 of the new report.

What do the high- and low-end scenarios indicate? Emissions growth slowed to a crawl in the 2010s, and COVID-19 brought emissions in 2020 down by a few percent, roughly to the same level as a decade ago. Experts assume a sharp rebound this year and next. Given longer-term global trends that include a dramatic swing away from coal, though, it now seems unlikely that the world will follow a high-end emissions path similar to SSP5-8.5.

On the other hand, following the lowest-end SSP1-1.9 scenario would take an extraordinary global effort. SSP1-1.9 assumes that total global CO2 emissions will drop by roughly 25% by 2030 and about 50% by 2035. A total of 137 countries have already thrown themselves behind a goal of carbon neutrality, most of them targeting 2050. If enough countries line up behind a roughly 50% cut by 2030 – with similar goals already set by the European Union, United Kingdom, and United States – then the SSP1-1.9 path could be within reach.

It’s unsettling, however, that all five of the new emission scenarios bring the planet to at least 1.5°C of warming over preindustrial levels between now and 2040.

It’s even possible that global temperature could briefly hit the 1.5°C threshold as soon as 2025, especially with any bump-up from a strong El Niño event. This result would likely precede crossing the threshold in a more sustained way. (Likewise, any volcanic eruption on the scale of 1991’s Mt. Pinatubo would tamp down global warming for one to three years, but it wouldn’t change the long-term picture.)

The main question, then, is whether big emission cuts soon can help the global climate from going past 1.5°C for the long term, which the IPCC showed in 2018 would raise the odds of more dire outcomes. The most optimistic scenario, SSP1-1.9, has global temperature nudging past 1.5°C by mid-century but then dropping back by late century. Such a relatively short excursion above 1.5°C might not trigger the worst outcomes, according to the panel.

If the world doesn’t cut emissions by half until 2050 – corresponding to SSP1-2.6, the next-best scenario of the five in this report – then global temperature could still push upward well past 1.5°C in the latter half of the century. It’s a stark reminder that half-hearted emission cuts are liable to bring less-than-satisfying results.

Extremes on Top of Extremes, with Some Regional Quirks

As long expected, rising global temperatures are continuing to boost the odds of intense, prolonged heat waves. Moreover, the global water cycle continues to intensify, with the heaviest downpours getting heavier and the worst droughts having even more impact on parched landscapes.

This assessment marks a new focus on the pile-on effects delivered by compounded extremes. Although the warming estimates from IPCC haven’t skyrocketed in this new report, there’s new recognition of how global-scale warming can translate into devilishly complex and destructive local and regional impacts.

“These compound events can often impact ecosystems and societies more strongly than when such events occur in isolation,” IPCC noted in an FAQ it prepared for the new assessment. “For example, a drought along with extreme heat will increase the risk of wildfires and agriculture damages or losses. As individual extreme events become more severe as a result of climate change, the combined occurrence of these events will create unprecedented compound events. This could exacerbate the intensity and associated impacts of these extreme events.”

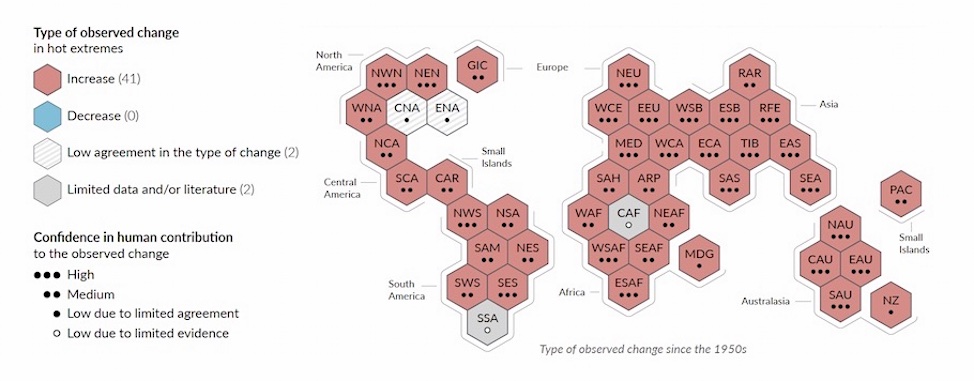

Already, human influence has likely increased the chance of compound extreme events since the 1950s, the IPCC assessment concludes. Among such events are the frequency of concurrent heatwaves and droughts on the global scale (high confidence); fire weather in some regions of all inhabited continents (medium confidence); and compound flooding in some locations (medium confidence).

Looking ahead, the report adds, “a warmer climate will intensify very wet and very dry weather and climate events and seasons, with implications for flooding or drought (high confidence), but the location and frequency of these events depend on projected changes in regional atmospheric circulation, including monsoons and mid-latitude storm tracks.”

One of the only regions on Earth where there’s little agreement on heat-related trends since the 1950s is central and eastern North America (see below). Episodes of record heat in this area have been juxtaposed at times with mild summers, cold winters, and widespread wetness, making it harder to separate the climate-change temperature signal from natural variability. Research into the “warming hole” is ongoing. There’s certainly no guarantee this region will continue to lag the world on overall warming – and for eastern North America, increases in extreme precipitation are deemed “very likely” by the IPCC.

The Longest-Term Legacy: Sea Level Rise

Because of its consensus nature, IPCC often puts metaphorical brackets around the kind of abrupt yet colossal changes often cited as tipping points. Earth’s climate is a lumbering system that doesn’t turn on a dime easily, even with the massive amounts of greenhouse gas being added to it. However, we ignore the risks of certain tipping points at our great peril.

As IPCC puts it: “Low-likelihood outcomes, such as ice sheet collapse, abrupt ocean circulation changes, some compound extreme events, and warming substantially larger than the assessed very likely range of future warming cannot be ruled out and are part of risk assessment.”

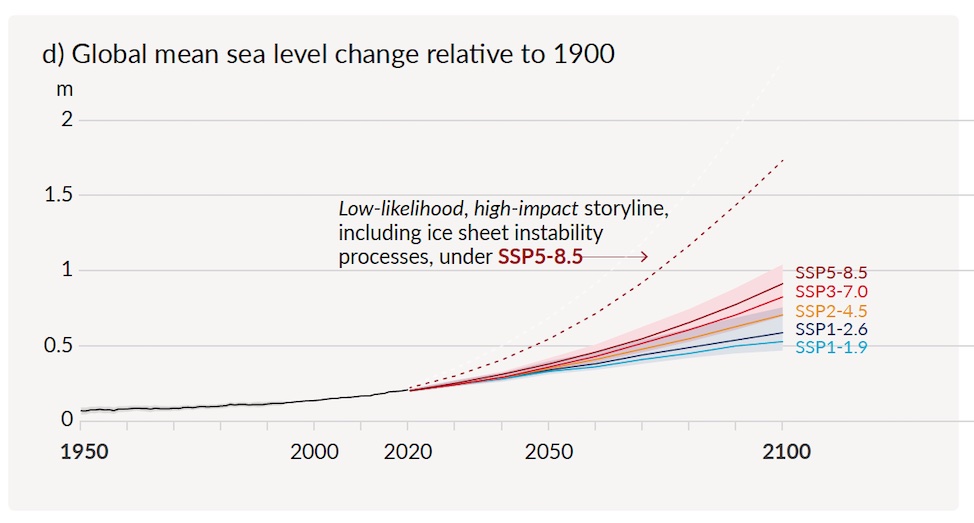

One example of how this needle gets threaded is with sea level rise (see below). The new projections are a bit higher than in the last assessment, but not dramatically so. They call for about 0.5 to 1.0 meter (1.5 to 3 feet) of sea level rise through 2100. Most of the difference occurs after 2050, with increasing late-century acceleration in the higher-end scenarios.

The elephant in the room is the dotted line showing what could happen if ice sheets in Antarctica become destabilized – a risk highlighted in key papers almost a decade ago, but still not a consensus expectation. According to the new assessment, “global mean sea level rise above the likely range – approaching 2 m [6 feet] by 2100 and 5 m [15 feet] by 2150 under a very high GHG emissions scenario (SSP5-8.5) (low confidence) – cannot be ruled out due to deep uncertainty in ice sheet processes.”

Global mean sea level change in meters relative to 1900. The historical changes are observed (from tide gauges before 1992 and altimeters afterwards), and the future changes are assessed consistently with observational constraints based on emulation of CMIP, ice sheet, and glacier models. Likely ranges are shown for SSP1-2.6 and SSP3-7.0. Only likely ranges are assessed for sea level changes due to difficulties in estimating the distribution of deeply uncertain processes. The dashed curve indicates the potential impact of these deeply uncertain processes. It shows the 83rd percentile of SSP5-8.5 projections that include low-likelihood, high-impact ice sheet processes that cannot be ruled out; because of low confidence in projections of these processes, this curve does not constitute part of a likely range. Changes relative to 1900 are calculated by adding 0.158 m [0.518 feet] (observed global mean sea level rise from 1900 to 1995-2014) to simulated and observed changes relative to 1995-2014. (Image credit: Figure SPM.8d from AR6 WGI Summary of Policymakers, courtesy IPCC.)

Even now, it’s clear that some coastlines are in far more jeopardy than one might think from the global projections. That’s because sea level rise to date, combined with everyday weather events, seasonal tidal cycles, and shifting ocean currents, is bringing increasingly frequent floods to some areas long before they’re inundated for good. The U.S. Gulf and Atlantic coasts are among those getting hit hard by such effects, including destructive “king tides.”

The IPCC warns: “In some areas, coastal flooding that occurred once a century in the recent past could be a yearly event by 2100.”

Perhaps the most profound threat from sea level rise is how long it will persist, an issue that’s long been acknowledged but that’s conveyed more powerfully than ever in the new assessment. “In the longer term, sea level is committed to rise for centuries to millennia due to continuing deep ocean warming and ice sheet melt, and will remain elevated for thousands of years (high confidence),” warns the assessment. It adds:

“Over the next 2000 years, global mean sea level will rise by about 2 to 3 m [7-10 ft] if warming is limited to 1.5°C, 2 to 6 m [7-20 ft] if limited to 2°C, and 19 to 22 m [62-72 feet] with 5°C of warming, and it will continue to rise over subsequent millennia (low confidence).”

Even with the “low confidence” caveat, this research-rooted statement is hair-raising – and it ought to be enough in itself to motivate the serious emission cuts that 30-plus years of IPCC reports have pointed toward.

There’s Still (Some) Time

The bleakness of the IPCC’s new assessment is leavened by new detail on how implementing prompt emissions cuts could help pull the world back from the brink and do so well within our own time. (The forthcoming Working Group III report will delve into much more detail on options for keeping climate change in check.)

Compared to the two higher-end scenarios, the two lower-end ones “lead within years to discernible effects on greenhouse gas and aerosol concentrations, and air quality…. discernible differences in trends of global surface temperature would begin to emerge from natural variability within around 20 years, and over longer time periods for many other climatic impact-drivers (high confidence).”

Even if some component of sea level rise is unavoidable going out centuries, “our emissions matter hugely for the long-term amount of sea level rise and how quickly it comes,” said Robert Kopp (Rutgers University), an author of the new assessment’s Summary for Policymakers.

It’s key to remember that IPCC assessments are meant to be policy-descriptive rather than policy-prospective. Rather than instructing global society on how to act, they give a portrait of what’s happening and what could happen based on how much greenhouse gas is emitted (i.e., “If the world does X, we can expect Y”).

It’s then up to the people of the world, individually and collectively, to arrive at alternatives to X through governmental, civic, corporate, personal, and diplomatic means – including processes such as the COP26 climate conference this November in Glasgow.

Also see: 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius of additional global warming: Does it make a difference?

This is why planned retreat is the best option. It is important to realize that natural coastal processes, especially sand erosion and deposition, must be given space (acreage) to operate. That means relocating infrastructure (roads, underground utilities, treatment plants, essential buildings) further landward. Planning for this change can reduce future expenses. (Like building sea walls that will eventually fail.)

Many coastal cities will be wholly dysfunctional without the efficient treatment of sewage at plants that are but a few feet above current sea level. That means the people living in the hills will be affected, even though they may be a mile from the ocean. (As an example the Hyperion treatment plant, which services millions in Los Angeles, occupies the coastal low ground. It recently was overwhelmed by inflow and sent millions of gallons of untreated sewage into the south coast bay. It is a health catastrophe now, and will only get worse with a rising ocean.)

Much of modern life will not seem so modern if treatment plants are overwhelmed.

“This is why planned retreat is the best option.”

What a profound comment.

What if “planned retreat” had been used in Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, Wall Street Bailout and, now, Covid? That is, to carefully and thoughtfully consider all alternatives rather than censor/vilify/intimidate those proposing alternatives.

But no, I can see all the Gamers, the Hedgies, the Profiteers lining up to game this Disaster just like all those before it. They are probably already doing so. And it is the Elite who own most coastal properties and who, in the US, already receive the largesse of Federal Insurance, aka Bailout. A hint of the problem:

https://www.propublica.org/article/four-ways-the-government-subsidizes-risky-coastal-rebuilding

If it is handled like Covid………….

How does planned retreat work if the sewage (sanitation) plant is flooded?

In the California’s Orange County, OC, northern OC sewage plant at the coast, services towns up to the LA County border, about 20 miles inland.

The concepts of Planned Retreat appears to rely on incremental rise in floodinn floods, and ignores critical infrastructure at the coast.

Not certain where you’re going. The planned retreat I anticipate is not some pre-conceived label. It is a recognition of the the relentless power of the seas and the the endless cost of attempting to resist it. Understanding that the cost of attempts to protect our coastal cities against sea level rise will be enormous and a recurring expense over millennia, it is better to plan for and retreat (incrementally?) and adapt to new conditions and spend our resources on long term solutions.

Possible solutions are planning for relocating coastal infrastructure and allowing for natural shoreline processes to operate. In many cases that means relocating sewage treatment plants (vital community resource). In others, it means removing coastal roads instead of armoring them to withstand increased storm waves; giving the shoreline the space to migrate inland naturally.

Every coastal city/site has unique conditions that need examination/planning before implementing a long range solution.

> Much of modern life will not seem so modern if treatment plants are overwhelmed.

I think that many US municipalities far from the coast may be facing similar issues in coming decades due to the lifetime of city sewer infrastructure and the cost of replacement with the same kinds of system.

I wonder whether lower-tech solutions such as in situ composting might be cheaper and more feasible in terms of limited real resources. That might work well in some settings (perhaps in suburban housing developments that have been converted into microfarms; close that nutrient loop!).

I know, I’m dreaming. I think of it as a form of “agency” (or maybe it’s more nearly “placebo”); it helps a little to alleviate the dread at the sense of looming doom. There will be lots to do to try to solve local problems as they arise.

We were introduced to something in my Common Earth course yesterday that NC folks might enjoy playing with in the face of the daunting challenges posed by the IPCC report. It’s a fairly sophisticated model of climate solutions that you can play with to see what it might take to keep under 1.5 C. Drop economic growth levels while increasing tree planting and see what happens. It’s produced by the MIT Sloan Sustainability Initiative. (The name’s a bit ironic considering who “Sloan” is.)

Climate Solutions Model

This modeling program is interesting. Unfortunately it does not have a hypothetical “pandemic” slider scale. If you set the population growth to the lowest possible (as an alternative to “pandemic”), then adjust all energy, resources, emissions accordingly (and assume that there won’t be any miraculous carbon removal technology), then you get to 1.6 C. Short of that, and it’s game over by 2100.

Just two points on this:

First thing is that the IPCC has consistently made ‘conservative’ projections which have proven to understate the short to medium term impacts. In one-off projections, being conservative is justifiable. But when it leads to consistent understated effects it becomes a form of bias and error. It does look like the IPCC has finally accepted this and has started to adjust, but unfortunately most of the damage has been done. Far too many policymakers over the past four decades have looked at the projections and thought ‘well, it looks bad, but its not the end of the world…’.

The second point is that again, the IPCC has tended to play down runaway impacts on the basis that they are by nature difficult to predict. Again, this seemed to be sensible and conservative, but is increasingly looking like a consistent form of error. Just because something is difficult to predict or measure does not justify ignoring it as a variable. They are finally coming around to addressing this danger more directly, but I think they are still playing down those hazards. I hate to go all Taleb on this, but as we’ve found out with Covid, ignoring long tailed (low likelihood, high impact) risks is a terrible basis for any policy based on hazard analysis.

> PlutoniumKun

OT, but I am trying to find a comment of yours on why the United States construction industry is so [family blogged]. I can’t recall the gist well enough to summarize it properly. Can you reconstruct or provide a link? (Or site search function is borked, or I would just look for it.)

I can’t remember enough of what I wrote to find it.

If its the post I’m thinking of, the essence is that:

The US (and UK) construction industry is far too dependent on sub contracting work (labour and plant). Essentially, this is profitable by allowing arbitrage between contractors who are willing to cut costs by abusing workers or other means. It also makes it much easier to ride out the bubble and burst nature of the industry by hiring and firing at will. It is unintentionally made worse by the unwillingness of the governments to provide long term contracts that would allow investment in plant and people.

European and Asian construction companies can frequently build cheaper and faster by keeping things ‘in-house’, allowing for a build up of know-how and more investment in technology. This can mean taking a loss during down times – often just paying people to sit at their desks doing nothing for months or even years on end. But the benefit comes when a new project arrives and can be geared up very rapidly. They can also invest long term in expensive plant, such as tunnel borers. This is aided by government contract structures that are either deliberately counter cyclical (for example, building public housing during recessions), or are constructed to allow long term certainty. An example would be the Madrid metro, where the selected contractors were guaranteed work over the entire 20 year lifetime of the project rather than have it split into subcontracted sections. It should be noted that EU procurement rules tend to make things worse, as they were designed primarily by UK and Irish neoliberals.

I have personal experience of this having worked for a US construction company which was in partnership with UK and French counterparts back in the 1990’s. When the project went through a 6 month blimp in funding, most of the US and UK engineers were made redundant, while the French company kept its staff (sometimes furloughed, but still on the payroll). When the project got the green light again – this time during an uptick in the construction industry, it found that it had to either massively increase salaries to get the engineers back (as most had already got other jobs), or had to hire new engineers and spent month retraining them. The french just picked up where they started and had their design work completed far ahead of the revised schedule. It was massively wasteful, and all in the name of ‘efficiency’.

This routinely happens in oil & gas and mining. Gear up, hire a full staff of engineers, geologists, skilled trades, laborers. Have a boom, rapidly throw together man-camp towns destined for ghost status later. Overcapacity. Lay off people by the millions. Financial types get scared, loathe to invest for years. When the surplus is finally worked off and demand rises, then the operators act surprised when they can’t find staff with ’10 years recent experience’ who want to go work crazy shifts in the back side of nowhere. Rinse, repeat.

A rational system would do as you recommend for construction; work on long term plans and maintain a normalized staff level. Even have paired subsidiaries–where one branch booms when petroleum prices are low, carrying the other branch through lean times. But no….

My brother was an offshore gas drill foreman, and he certainly experienced that. He was fortunate in that at the end of the last off-shore boom when he suddenly found himself in demand again after a lean decade he was able to extract a very good contract with a pension. Plenty of others weren’t so lucky.

I cannot reference PlutoniumKun’s comment you have in mind, however this might help:

“America’s Political Economy: The Inefficiency of Construction and the Politics of Infrastructure”, Adam Tooze, https://adamtooze.com/2017/06/06/americas-political-economy-inefficiency-construction-politics-infrastructure/

I recall there was a NakedCapitalism post or a link discussing the remarkable inefficiency of the US construction industry a few years ago. You might find PlutoniumKun’s comment there(?).

Don’t worry, PK. Go all Taleb. His Statistical Consequences of Fat Tails will back you up.

Interesting, your comment about how the UN committee who wrote the report assessed the risk of making too strong a case. From your perspective, it could be said that they appeared to come down on the side of risk aversion, as the risk of getting a negative reaction to too strongly stated a case seemed to them to be a bit high.

I can’t recall the author, but a few years ago I read a fairly detailed assessment of the main sources of error and bias within the IPCC. Some came from external lobbying, but a lot of it was natural scientific caution, of the ‘we can’t prove this, so lets leave it to one side for the moment and focus on what we can prove’.

But as the author pointed out out, while in general science being cautious about over interpreting data is good practice, when you are consistently making that cautious call on one side of the argument, then the result is a built in bias. In this case, it is a biased assumption that excess CO2 won’t cause too many problems. It is, in effect, a built in problem with the standard scientific method as applied to risk assessment situations.

We’ve seen this happen with Covid, where entirely inappropriate arguments based on scientific levels of ‘proof’ has been applied to minimally risky precautions, such as masks, stopping international travel, or giving everyone vitamin D.

Can I ask. If courses of action do not withstand any scientific scrutiny (proof it works), isn’t there a risk that people think I’m doing all these things so I must be either safe (in the case of Covid), or making a difference (environment). When neither is so (I’m not saying masks don’t keep you safe, I wouldn’t know).

I agree nothing is certain, even a court is only beyond REASONABLE doubt.

This is the core of the problem. Lots of scientists have said some very stupid things because they haven’t thought through the full balance of evidence. Applying the same criteria for ‘proof’ for, say masks or vitamin D, both of which have very few downsides in terms of cost or safety as you would for a novel new biochemical compound makes no sense whatever in terms of risk assessment. But this is exactly what many health authorities have done, and continued to do during Covid.

I think there is a core problem in many fields of science in that scientists are trained to satisfy the criteria set by their peers for ‘evidence’ or ‘proof’. This is perfectly fine within a tightly defined field of research, but it can lead to terrible outcomes when they try to apply the same criteria outside their area of expertise. And add to this the problems of uncertainty or fat tailed risks (as described by Taleb) and you have an even greater recipe for mass confusion among the so-called ‘experts’. By this I mean that just because you are a brilliant biochemist or virologist, it does not mean that you know what you are talking about when it comes to overall public health matters.

Isaiah Berlin talked about this with his analogy of the Hedgehog and the Fox. Most great scientists are hedgehogs. But when deciding on public policy, you need to hear from a few foxes as well. Unfortunately, it seems our establishment bodies have been singularly bad at producing them. Its been painful at times to see how many public health bodies have been at sea over Covid, and I don’t think that collectively science has covered itself with glory either over climate change.

This is not quite correct about court judgements. Simplifying, if the case is a criminal one, then the judgement is one based on being beyond reasonable doubt; but if it is a civil case, the criterion is that the judgement only needs to be based on the balance of probabilities.

PK is quite right about the possibility of built-in biases in scientific reasoning in certain contexts.

Yes, but in this goofy spin-world we live in, the publishers can be less concerned about accuracy, and more worried about being dismissed as wild-eyed crazy tree-huggers. If you get put in the wacko alarmist box, no one listens to a word you say, however valid or correct it might be.

how true is that. And once you’re branded (rightly or wrongly) then it’s only ever about the loony messenger and never the message. I sometimes felt Trump suffered from this.

The fat tails of the events modeled in the many climate models are only one concern. The climate statistics are not static — means and variances change as the climate grows more angry. The fat tails can grow fatter.

I have the impression that much of the content in the IPCC reports is derived from climate models. That might be well and good if the models were complete and all the parameters well known. The climate of the geologically recent past experienced many abrupt and wrenching changes in response to a much smaller forcing than Humankind has wrought. The climate models are fine in producing things like carbon budgets and refining calculations of the Earth’s temperature sensitivity to CO2 in the atmosphere. Budgets work nicely to enable Humankind’s continued practices that dump CO2 into the atmosphere. Budgets work nicely for constructing Markets. I view the IPCC as enabling Neoliberal solutions.

Jeremy, I think your final sentence is too strong. More prefereable, for me at least, is to say that the report does little or nothing to undercut neoliberal practices.

And I should add ‘or its narrative’.

Well that seems good. There’s more people signing up than I thought.

Someone still needs the industrialized countries with high exports to work on this. But a place like China needs an environmental movement, not to mention a labor movement.

I don’t find net zero by 2050 pledges convincing, whether they’re made by private corporations or governments. They allow for far too much can-kicking and faith in technologies that either don’t exist or haven’t been proven to be economically viable, assuming that the dramatic transformation we need can wait until 2030 or 2040 to really get underway. The key takeaway from this report (and we’ll have to wait for WG3 to see if this plays out) is if an entity is doing anything less than aggressively cutting fossil fuels and emissions and deploying the technologies we already have in the next decade, you’re engaged in denial.

David Roberts has been good on this recently in discussing the climate aspects of the US infrastructure and reconciliation bills.

Also wanted to mention that Canada has a net zero by 2050 pledge. Nothing we’re doing right now is going to help us get there. In fact our federal government bought an $11 billion pipeline project that would have otherwise failed, to give our shitty oil safer transport and access to new markets. All while insisting they have a serious climate strategy.

@Eelok: Aye. I also find the “net zero by 2050” pledges unconvincing. Right now most of the pledges are simply words on paper. They don’t change anything.

For change to happen, the pledged have to be backed by real plans. Detailed plans that address as many sources of CO2 emissions as possible. Feasible plans that honor real-world resource restrictions and can be implemented in a timely manner. Effective plans that actually perform as advertised.

Most of the “plans” out there are PR pieces filled with sound bites, platitudes, and arm-waving. Other ignore critical requirements or presume resources that aren’t available. A few countries have actually taken honest shots at it, but their plans failed. Take Germany’s Energiewende, for example:

In 2011, German authorities decided to phase out nuclear power based on an analysis by Klaus Topfer and Mattias Kleiner, who said that Germany could phase out nuclear and fully transition to renewables within a decade. Well, the decade has come and gone, and renewables provide less than 50% of their electricity. New installations have largely stalled out. They’re still burning large amounts of brown coal. The Nord Stream 2 pipeline is about to go online. And electricity prices for German consumers have doubled. Topfer and Kleiner’s analysis was clearly flawed.

It is not climate change. It is not big energy ruining the world.

It is simple ARSON.

Some so-called greenies and jacobins are willing to burn down the nation in order to promote their deindustrialization and redistribution agenda.

https://sacramento.cbslocal.com/2021/08/11/college-professor-accused-of-setting-fires-in-dixie-fire-area/

Or, is it more accurately terrorism since the goal is to force political and socioeconomic changes upon a society that the society would not otherwise tolerate?

You read too many comic books. None of your alternative hypotheses hold water as there is no evidence for them. There is some fragile evidence for arson in one of the fires — though not the largest. But the rest, floods and fires both, look like what they are, consequendes of climate change.

I can’t quite tell if you have an especially dim opinion of the commentariat’s intelligence, or a drastically over-inflated estimate of your own.

The dry lightning strikes in the bay area this time last year approximated a terrorist/arsonist in a fashion in that it wasn’t a whole lot different than say a bad guy from the middle east (stereotypes happen-could just as easily be somebody from Cali that wants it all to burn down) who lands in SF, is gone over with a fine tooth comb and the authorities find nothing.

He then rents a car, drives over to O’Reilly auto parts and buys 36 road flares, setting off fires all along the foothills of the Sierra from the Gold Country to the Kern. There’d be no way really to stop him.

When we lived in LA County and would drive north and see the Los Angeles Aqueduct, the main water supply for the city, right out there in the open, for miles and miles and miles, I would shudder.

Wow. Guy is innocent until proven guilty but if this is the guy who did it, it’s pretty wacky.

If people won’t even willingly wear masks during a pandemic, there is little hope of successfully addressing climate change. So much for the “rational actor” model of human behavior!

Overall, in highly developed ostensibly representative governed (Western) countries, climate policy like worker’s rights largely continues to come under the heading of campaign promises by those who make policy. Short term profits, on the other hand, continue to come under the heading of pants on fire must accomidate immediately -and make it look like I had no choice- by those who make policy (I’m abbreviating the well known and oft discussed process by which this happens).

And this continues with what must be considered only half-hearted, hollow campaign promise category, non effort effort to recognize, never mind address the problem, such as climate accords with no teeth, or vague (and frighteningly irresponsible) promises that technology will solve all, given the extraordinary starkness of the situation on the ground. If fires consuming entire parts of states, entire water systems disappearing, hurricanes wiping out entire countries, heat waves never seen before in contemporary history, aren’t enough to make our so called leaders take climate change seriously, I don’t see how a more aggressive IPCC report will do it, at least in any thing even approximating a workable time frame.

Seriously addressing major calamities in our (again Western) history always seem to take place well after the event. As we are seeing now, it doesn’t work well for pandemics or major economic depressions and will work even less well for near or total extinction events.

Humans can be persuaded to believe and do almost anything. Fly a hulking plane to drop tons of explosives on cities, killing sleeping children and old people? No problem.

Believe that Father, Son and Holy Ghost sit up in the sky, directing human traffic, and be willing to burn alive people who believe otherwise? No problem.

Believe that human activity including the burning of fossil fuels, blowing up mountain tops, clear cutting forests, letting toxic tailings from mining activities leach into waterways, allowing top soil to dry up and blow away, is destroying the livability of Earth? Nah.

One thing I amuse myself by imagining …… List the top five greenhouse-gas-emitting things you could do without:

1. Those lumbering red Coca Cola trucks delivering sugary, bubbly water in plastic (!!) bottles to stores.

2. Plastic (!!) holiday ornaments (and home decorations) shipped from Asia on ginormous cargo ships.

3. Cheap (and not-so-cheap) clothes shipped from Asia on ginormous cargo ships.

4. Yellowish slimy chicken and pink slimy beef from CAFO’s.

5. A new smart phone every two years.

Oh, and how about ‘rationing.’

I remember WW2 ration books. Everybody got a stickers for a pair of shoes, meat, a new winter coat. Didn’t matter that you had enough money to buy a thousand pairs of shoes. You were allowed one pair per year (maybe two.) Sure, there was a black market, but the penalties, if you were caught, were severe.

Ration gas. Year one, start with a generous allowed amount. Then decrease, allowing people to adjust their lifestyles.

Have climate town meetings, with suggestions for reducing greenhouse gas emissions coming from the grassroots up though state, regional and national levels.

And don’t say we can’t do it. This is a nation that went from building fewer than 1,000 war planes in 1939 to producing over 96,000 in 1944. OK, we had a nascent plane manufacturing culture, but we also had a belief that, like the Seabees, “The difficult we do now, the impossible takes a bit longer.” Scratch the American Couch Potato and you find a Seabee. Just a bit out of practice.

I love this:

“And don’t say we can’t do it. This is a nation that went from building fewer than 1,000 war planes in 1939 to producing over 96,000 in 1944. OK, we had a nascent plane manufacturing culture, but we also had a belief that, like the Seabees, “The difficult we do now, the impossible takes a bit longer.” Scratch the American Couch Potato and you find a Seabee. Just a bit out of practice.”

Attitude counts for a great deal in human endeavors.

If I had a magic wand, this aspect of our current culture would get a major “twinkling”.

=====

Do I advocate building war planes? Certainly not. Did I need to point that out? I hope not.

Re: building war planes. Well, we have, as a nation, tended to get off our tushies only for a good ole’ war. It’s all a matter of focus; concentrate on one thing: defeat the enemy.

The entire planet changing is too big to even comprehend, much less develop a plan and get the entire nation (almost) to go along. So, maybe, getting people together on a local level: e.g., how has the ecosystem of the Gulf Coast changed over the past 100 / 50 / 25 years. The ‘elders’ know. What factors /actors are responsible. What changes can we make.

All regions of the country are experiencing changes, but they differ; more rain, drought, fire, flooding. Some are subtle (my spouse, having grown up in the house we now inhabit, and been ‘away’ for 40 years, remembers veggie gardens that did not have to be fenced in like a high security correctional facility to protect against marauding deer. And the slugs! Aiyee!)

Yes! Little boxes of plastic forks, for heaven’s sake, shipped across the ocean. What the heck??

Eclair, you make a good arguement.

Contributing solutions just all around–at Human scale and not Technical scale.

Ration gas–ironically I have been thinking on this a lot over the last week. An example of what manifestations that ‘Radical Conservation’ can have.

Rationing would raise the ISSUE to everyones consciousness, and force decision making–a good thing.

It would also dovetail nicely into the ‘Community Building around Action’ for your second, almost benign, second suggestion:

Have climate town meetings

Because everyone has a stake and needs to feel ownership, as Individuals and as Communities.

Also, as you illustrate, because bottom up starts simple, has more variations , and better ‘buy in’

‘One big pill’ isn’t going to fix anything, anytime, in time.

https://rebellion.global/news/#blog

and this

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/extinction-rebellion-plan-endless-mass-climate-change-protests-in-london-d7bgzmwp0

I honestly think that your description of the WW2 rationing system will be our future blueprint as things start to fall apart. Any changes in the end will always have to be on a local level and so yes, town meetings will be a big feature rather than waiting for a Federal government or even a State capital to take any sort of lead. Going by their pandemic response, most State governments will be still denying that anything has to change.

I’d go even closer in looking to the past, when austerity was a way of life during the Communist bloc party, where lines might form for canned yams. It was a rough method of getting people used to living with less, but it worked for 40 years.

You say “…Believe that human activity including the burning of fossil fuels, blowing up mountain tops, clear cutting forests, letting toxic tailings from mining activities leach into waterways, allowing top soil to dry up and blow away, is destroying the livability of Earth? Nah. ..”

I’m not sure the majority of people, who aren’t interested in change (not saying I am) don’t believe those things effect the liviablity of the planet. I just think for various reasons (I wouldn’t think to know them all), that they’re not going to change. Not so much not convinced as not motivated.

Or maybe futilitized. Or maybe effitized.

Or maybe have already decided to ” Let’s let this bitch burn to the ground in hopes the fire reaches the Big House on the Hill.”

Rationing and Government directed investment in producing war planes, and some of the Government actions during the Great Depression were done before Neoliberalism. Actions and measures that were effective in handling past threats to our Society would be effective now. But they are not Market solutions. Neoliberalism cannot allow non-Market remedies. The failure of the Market has been clear for decades, yet the Power Elite continues to profit itself by dealing with the failures of the Market by creating new Markets. Until something changes the morality of our Power Elites Humankind faces an unhappy future.

Or until something exterminates the Power Elites we have now and replaces them with a better set of Power Elites.

Yesterday Biden asked the OPEC to increase oil production!

I don’t see any discussion of impacts to agriculture. Hopefully that will be part of the reports by the other working groups. Sea level rise over decades just doesn’t motivate immediate change quite like the threat of crop failures and famine from extreme heat waves, droughts, and floods.

That omission is indeed glaring. How Climate Chaos might affect the many tipping points of human systems is a potato too hot for the IPCC to touch. I believe one of the later reports will discuss possible impacts of Climate Chaos on human systems — touch upon them but lightly.

Until China is addressed all the rest is just further abusing western corporations that have already done most of the heavy lifting and extracting further from the lower and middle classes without any actual demonstrable ‘climate’ benefit.

Aside:

Exxon paid for the Valdez. Corporate Liability.

BP paid for the Deep Water Horizon. Corporate Liability.

We accept ( demand? ) it for petroleum, gas, and minerals providers..

Why should pharma or anyone else be exempted from liability for their products and any/all environmental and/or human damages they or their products may cause?

China?

Why not consumption in general?

Because shipping matter to China in order to turn it into crap to ship back here requires the additional carbon skyflooding of shipping it there and shipping it here, on top of the carbon skyflooding of turning the matter into crap.

If we turned the matter into crap right here, at least we would spare ourselves the additional carbon skyflooding of all the shipping of matter to China and crap back to here.

If we can terminate economic contact between China and America, then we can start to focus on “consume less home-made crap” right here, and move on to less crap and more conservation.. 2X less shit and 1X more shinola.

But that won’t happen as long as we have Free Trade Agreements and World Trade Organizations.

One sign of a commitment to energy conservation right here would be a rigid hard ban on 5G technology here in America. Not just Huawei’s 5G. Anyone’s 5G. Everyone’s 5G. Ban 5G from America. People who won’t even support that . . . won’t support anything at all.

And that would be a decision to go Full Metal Joker and watch the world burn.

China?

Why not consumption in general?

Chinahand Peter Lee is a bit more gloomy about this: https://www.patreon.com/posts/unlocked-end-of-54113371

If he is correct, then we should all take 5 minutes to go to the kitchen, stick our head in the freezer, and kiss our ice goodbye.