Out in the Sonoran desert, about 25 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border, the Arizona city of Yuma and its neighboring suburb Somerton continue to host a steady stream of asylum seekers.

Some days the city has seen more than 100 asylum seekers. On other days far less, but as of late, the daily count has stood at a steady 25.

These individuals find themselves in the area at the behest of U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP). Entering the country to flee persecution in their homelands, the people entering Yuma County start their journey by submitting themselves to CBP custody as they undergo screenings prior to receiving admittance.

However, as America grapples with an immigration system that experienced a new peak of over 178,000 land encounters at its Southwest border during the month of April, Arizona's migration processing teams find themselves stretched for resources.

Under normal circumstances, asylum seekers are processed within 72 hours, then transferred to U.S. Immigration and Customs' (ICE) Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) unit in Phoenix, where those who pass background tests are released from detention while they await a legal hearing for their asylum claim. Individuals released from detention may travel to other areas of the country and stay with friends, family, or sponsors as they wait to present their case before a judge.

Right now, in Yuma County things look quite different.

Given the current numbers of migrants, ICE's ERO unit in Phoenix lacks a sufficient number of beds to host Yuma's asylum seekers, as well as enough adequate transport to take them to Phoenix. Under CBP's National Standards on Transport, Escort, Detention, and Search, the agency must generally hold individuals for no more than 72 hours. When the time elapses, asylum seekers are dropped off at the nearest viable town.

That often means Yuma or Somerton.

Under the Anti-Deficiency Act of effective September of 1982, CBP must avoid spending federal dollars beyond its appropriation, meaning the agency needs to provide the lowest available transportation cost. So, instead of being transported to a city like Phoenix with a robust nonprofit support system and steady means of transportation, asylum seekers find themselves in Yuma and Somerton.

As somewhat isolated cities with populations of 96,000 and 16,000 respectively, and a GDP per capita of $30,000, less than half the national average of $65,000, the communities face challenges as they respond to the situation.

Yuma's mayor told Newsweek that if the area's nonprofit organizations had not risen to the occasion, Yuma could have found itself in a state of crisis.

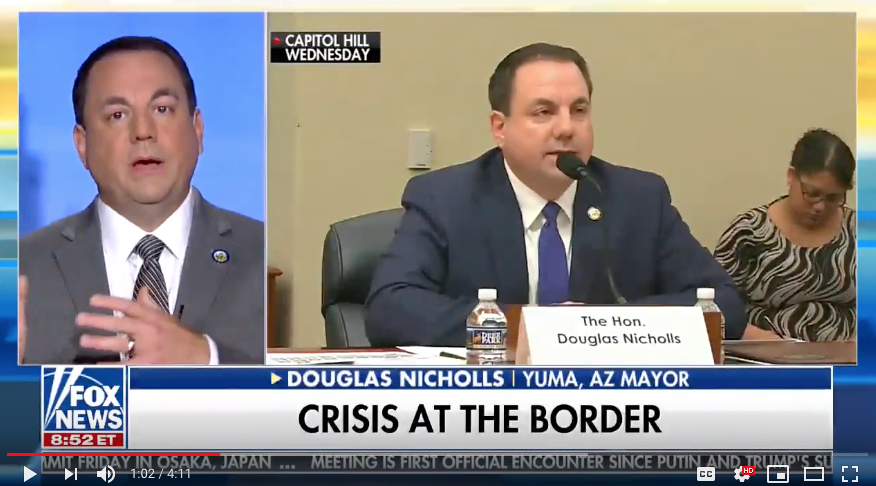

"Nonprofits are extremely critical to making sure that there aren't additional humanitarian issues," Yuma's Republican Mayor Douglas J. Nicholls told Newsweek. "The robustness of the smaller communities along the border just doesn't exist."

Prior to receiving aid from Yuma's nonprofits, Nicholls said hundreds of asylum seekers found themselves on the city's streets. The city's small size and economic pressures had already stretched nonprofit and homeless shelters networks. But since the pandemic, those problems only worsened.

Currently, only one bus comes on a daily basis to transport individuals from the city, and a second bus comes periodically through the week. Nicholls said some people wait longer than three days for a ticket.

To keep asylum seekers from spending days outside in the 80- and 90-degree heat, Campesinos Sin Fronteras, a Somerton nonprofit historically focused on supporting the migrant agricultural community, not asylum seekers, stepped up.

The agency stationed volunteers to support migrants through providing personal protection equipment and helping them take the initial steps to connect with their U.S. contacts and arrange passage to their final destination. For those in need of shelter, Campesinos works to connect them with transitional centers.

Along with Campesinos, the Regional Center for Border Health, a nonprofit clinic, arranged for free COVID-19 testing and started funding the bussing of migrants to areas with greater capacity to care for them, like Tucson and California's Imperial Valley. For those in need of housing, churches like Iglesia de Dios Nuevo Nacimiento provide safe shelter.

However, despite their efforts, the phenomenon still exceeds Yuma's capacity to handle it.

"We did not expect for this to happen," Campesinos spokesperson Janeth Gonzalez told Newsweek. "We are not equipped, nor do we have the resources to respond right away, but we've quickly adapted."

Gonzalez said many of the individuals arriving in the area come from countries ranging from Romania to Brazil, from Cuba and Haiti to Venezuela. The diversity in experiences and spoken language presents a number of logistical challenges for groups like Campesinos trying to connect asylum seekers information and medical services. Some of the individuals have limited means of communication, and many have no idea where they are or how to get where they intend to go.

They want to make this experience as bad as possible to dissuade other people from doing it. That's kind of the underlying assumption of a lot of immigration enforcement actions.

Jeremy Slack, a professor of geography who runs the Immigration and Border Communities Research Experience for Undergraduates at the University of Texas, El Paso said the challenges facing asylum seekers are intentionally worked into the system itself.

"A lot of this is predicated on the fact that they want to make it hard on people," Slack told Newsweek. "They want to make this experience as bad as possible to dissuade other people from doing it. That's kind of the underlying assumption of a lot of immigration enforcement actions.

Even with a legal immigration process like asylum, Slack said the system intends to deter others through the experiences of those going through it. This deterrence may lead to a long-lasting impact on those who go through the system. A study published by the Journal of the American Medical Association wrote that a growing body of evidence shows that policies of deterrence add to the post-migration stress already facing asylum seekers, leaving them more vulnerable to psychological disorders in the future.

Addressing this problem starts with securing reimbursement for the city and nonprofits involved. Nicholls has requested funding from FEMA. But beyond the short-term economic remuneration, Nicholls said the system needs reform, which he and the city are looking to help push.

Nicholls has called on the Department of Homeland Security to provide transportation to communities with greater capacity to support those seeking asylum. He also hopes to use an open room in Yuma's federal courthouse dedicated to asylum seeker cases to help expedite the process. He hopes that by supporting the hearing process those seeking safety will be welcomed into the country sooner, as he knows they've already faced a number of challenges on their way over.

"People that are being transported to this country face rape, extortion, neglect, and potentially death," Nicholls told Newsweek. "Until we have conversations (about what is happening), I think we're going to continue as a country to be divided. But once we do have that conversation, I don't know anybody in this country that will find these things acceptable."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Alex J. Rouhandeh serves as Newsweek's congressional correspondent, reporting from Capitol Hill and the campaign trail. Over his tenure with ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.