Some time ago, I learned about a strange and heartbreaking moment that had transpired outside Sitting Bull's cabin while he was being assassinated by tribal police during an arrest. A horse was tethered to a railing and at the sound of gunfire, it started to "dance," trained to do so while he was in the Wild West, Buffalo Bill's famous spectacle, which Sitting Bull was a part of for four months during 1885.

For months I couldn't shake the image and as I began to look into it, I learned that the horse had been a gift to Sitting Bull from Buffalo Bill, presented to him when he left the show. The fact that Buffalo Bill had given Sitting Bull a horse was significant. This was the animal that transformed the West—and was stripped from the tribes in order to vanquish them. It was a gift Sitting Bull treasured, along with a hat Cody had given him. After Sitting Bull was killed, Buffalo Bill bought the horse from Sitting Bull's widows and, according to some accounts, rode it in a parade. And then the horse disappears from the record.

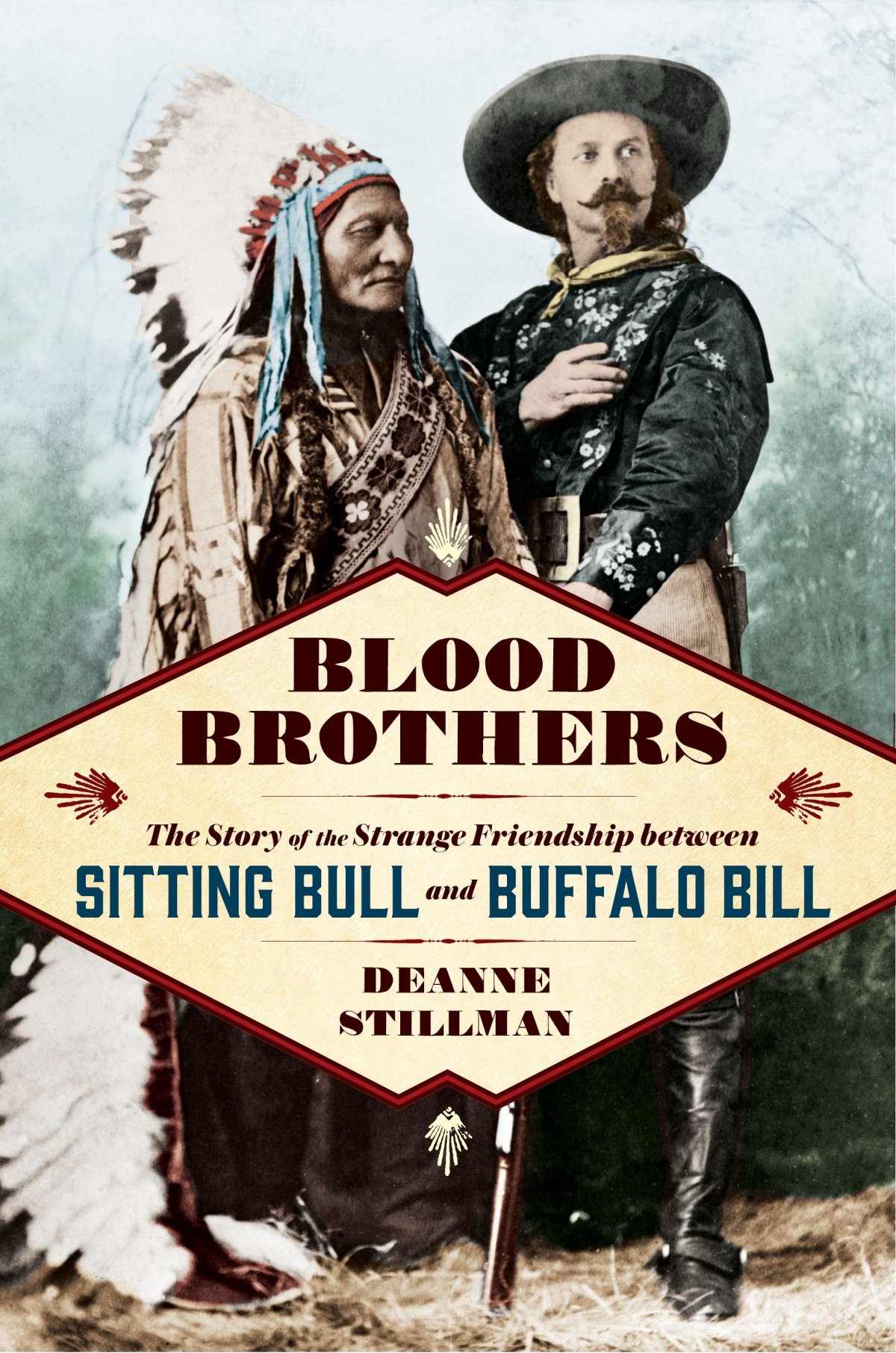

It was the legend of the dancing horse that led me into the story of Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill, for it symbolized so much. Later, as I was well along that path, I came across another image that also captured my attention. It was taken for publicity purposes while Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill were on tour in Montreal, and its caption was "Foes in '76, Friends in '85." I began to imagine these two men on the road, Sitting Bull on that horse, criss-crossing the nation, visiting lands that once had belonged to the Lakota, appearing as "himself" on crowded thoroughfares that were built on top of ancient paths made by animals and the people who followed them, with William F. Cody, another mythical figure of the Great Plains, re-enacting wartime scenarios that had one outcome—the end of the red man and the victory of the white—leading the whole parade in a celebration of the Wild West that became the national scripture. What were the forces that brought these two men together, I wondered, and what was the nature of their alliance? Theirs was certainly an unlikely partnership, but one thing was obvious on its face. Both had names that were forever linked with the buffalo, and both led lives that were intertwined with that animal. One man was "credited" with wiping out the species (though that was hardly the case) and the other and his fellow Lakota were long sustained by it. They were, in effect, two sides of the same coin; foes and then friends, just like the photo caption said. Here were two American superstars, icons not just of their era and country, but for all time and around the world. What story was this picture telling and how was it connected to the dancing horse outside Sitting Bull's cabin?

To find out about other underpinnings of this story, I spent much time on the Plains. I have attended memorials of the anniversary of the Little Bighorn, the infamous battle from which this country has yet to recover, the one in which the Lakota and Cheyenne defeated Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer and his 7th Cavalry in 1876, leading to the roundup of remaining "renegade" Indians, the flight of Sitting Bull and his people to Canada, his ultimate return as a pariah only to be blamed for the murder of Custer and then celebrated as a brave and defiant rebel. I have visited Mt. Rushmore and the Crazy Horse Memorial nearby, traveled the Badlands where the remnants of the horse tribes sought refuge after the massacre at Wounded Knee, explored the terrain of William F. Cody in Cody, Wyoming, the town that he founded. I have communed with wild horse herds that are said to be descendants of Buffalo Bill's horses, on their home turf in Wyoming where they flourished until recent round-ups obliterated them and their history, and I have spent time with mustang herds on a sanctuary in South Dakota where descendants of cavalry horses live out their lives, and where descendants of Sitting Bull's horses carry on in a national park nearby and where at night, under the northern lights, you can hear the thundering hooves of the ancient steeds if you get quiet and listen for the sounds behind the winds that are forever wailing.

What divided Indians and the white man during Sitting Bull's life is still in play. Out on the Great Plains last year, a staging ground for the original cataclysm, there was a face-off in North Dakota at a place called Standing Rock, where Sitting Bull was essentially a prisoner when the land became a reservation and before that lived in its environs as a free man. An oil company would like to force a pipeline through sacred lands on Indian territory and those who first dwelled there were saying no. They feared a spill that would contaminate the waters which flow nearby. They were joined by thousands of Native Americans from across the country, who arrived on foot, by canoe and on horseback. It was the largest such gathering of the tribes in one place in America's history, and many of these tribes were historic rivals. Thousands of war veterans also came to Standing Rock in support of Native Americans.

To celebrate this union and mark the victory against the pipeline, on December 6, 2016, at the Four Prairie Knights Casino and Resort on the reservation, descendants of soldiers who had fought in the campaigns against Native Americans knelt before Lakota elders. They were in formation by rank, with Wesley Clark, Jr., son of former army general Wesley Clark, Sr., at the forefront. "Many of us, me particularly, are from the units that have hurt you over the many years," Clark said. "We came. We fought you. We took your land. We signed treaties that we broke. We stole minerals from your sacred hills. We blasted the faces of our presidents onto your sacred mountain…we've hurt you in so many ways but we've come to say that we are sorry. We are at your service and we beg for your forgiveness." In return, Chief Leonard Crow Dog offered forgiveness and chanted "world peace" and others picked up the call. "We do not own the land," he said. "The land owns us."

The ceremony was marked by tears—and then whoops of joy. Outside, the winter snows began to overtake the plains and soon, the veterans dispersed to the four directions.

Elsewhere, atonement and forgiveness between the white and red tribes has unfolded in a quieter manner. After a prolonged battle over who determines American history and to what end, the U.S. Board of Geographic Names recently voted to change the name of Harney Peak in the Black Hills of South Dakota—"the heart of all there is" for the Lakota—to Black Elk Peak. This highest peak east of the Rockies was where Black Elk had his famous vision about a mythological figure known as White Buffalo Calf Woman, a dream that revealed the role of the buffalo and the horse and the four directions in the life of his people and showed how all these elements were woven together. The peak where it came to him was not the place where he physically had his vision (he was a young boy, at home), but the place to which his spirit traveled while experiencing it. As it happened, the site later became known for something else—the Massacre at Blue Water, in which Brule women and children were killed in 1855, and it was named for General William S. Harney, who led the assault, even though that massacre occurred in Nebraska, not South Dakota.

The name change is significant. Black Elk was the second cousin of Crazy Horse, and he participated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn as a young boy. Later he fulfilled the vision that transported him to that mountain peak, and he became a medicine man. His teachings were passed on in Black Elk Speaks, regarded by leaders of many denominations as one of the great works of spiritual import. When the sacred hoop of his kind had been broken, when the Great Plains were no longer limitless and the circle that linked all elements and all living things was severed, he joined the Wild West and traveled the world with Buffalo Bill. "Pahaska had a strong heart," Black Elk said when Cody passed away, invoking the native name meaning "Long Hair" which many Lakota Indians used for both Buffalo Bill and Custer. It is a statement that many do not know or have forgotten.

In a recent ceremony to mark the transfiguration of the peak, two families gathered in a circle at a nearby trailhead. They were seventh-generation descendants of the general's family, according to Indian Country Today, and the family of the chief whose people were wiped out. The rite was organized by Oglala Lakota Basil Brave Heart so that members of the general's family could apologize to members of the chief's, and to seek forgiveness and healing. In turn, members of the chief's family were there to publicly forgive and support the reconciliation offered by the renaming. The event had been several years in the making, involving many talks between the families, prayer walks, and facing down a range of anger and resentments in both communities. In fact, the renaming was something that few believed would happen.

When the ceremony at Black Elk Peak concluded, members of the Harney and Little Thunder families smoked the peace pipe and embraced, planning to continue acts of public healing between whites and Native Americans, culminating in the near future with a long-needed event at Wounded Knee. "Foes in 76, friends in 85"—the slogan deployed for the partnership of Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill—could have been the caption for a photograph of the ceremony at Black Elk Peak, with only a change of dates. It would seem that America has embarked on the painful and long-needed journey of healing our original sin—the betrayal of Native Americans. This is the fault line that runs through America's national story, and perhaps the brief time that Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill were together can serve as a foundation upon which this rift can be fully repaired.

And now, let us return to their final connection—that horse Cody gave to Sitting Bull after his last performance in the Wild West. A while ago, I called Chief Arvol Looking Horse to seek his insight into this matter. He is the 19th Generation Keeper of the Sacred White Buffalo Pipe for the Lakota Indians, which was given to his people by the woman in Black Elk's vision. He has led ceremony regarding environmental and other sacred concerns at Standing Rock, the United Nations, and elsewhere. I had met him several years earlier at a wild horse preservation event in Las Vegas; at its conclusion, everyone in attendance joined him in a prayer circle in a ballroom at the South Point Hotel, hotels and their ballrooms with garish chandeliers being the location of many such events because they are among the central gathering places of our time. "What was the symbolism of the dancing horse outside Sitting Bull's cabin?" I asked him in our phone conversation. "Was he responding to the sound of the gunfire, as the story goes?" There was a long silence and I hesitated to break it. But after a few moments, this is what he said: "It was the horse taking the bullets," he told me. "That's what they did."

I had long thought about the horse outside Sitting Bull's cabin at the time of his killing. He too was part of the Ghost Dance, I realized, the apocalyptic frenzy which swept the horse tribes, calling for a return to the old ways when all was right and the buffalo were plentiful. It was at the height of this dancing that Sitting Bull was killed, blamed yet again for leading "renegades" in an act of insurgency. In one of history's near-misses, his assassination was nearly headed off by Buffalo Bill, dispatched to Sitting Bull's cabin by General Nelson Miles to convince his old friend to surrender. And thus, it was presumed, that the dancing would end, along with Sitting Bull's power. But en route, Cody was waylaid by enemies of Sitting Bull, given false information and plied with drinks. Most likely, he was fending off a hang-over as he left Standing Rock following his failed mission.

When Chief Looking-Horse suggested that the dancing horse was something more than I had first imagined, that it was the horse metaphorically taking bullets for Sitting Bull as he was being assassinated, I had to take a moment or two, and I am still taking them, for of all the images that have come my way while writing this book—Sitting Bull's son handing Sitting Bull's rifle to the authorities at his father's request upon their return from exile; Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill meeting for the first time in Buffalo, of all places; Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill posing for a photograph in full dress – this is the heartbeat behind the story, the trinity of the West, the two icons nearly crossing paths just before Sitting Bull died, and joined in the end by a horse that "died" along with our great Native American patriot.

And now, I must add a final note: not everyone believes that the horse danced. But I do. And that's how I came to write Blood Brothers, and perhaps after reading it, you'll have your own thoughts about what happened on a winter's dawn of 1890, and all of the matters and forces that preceded it.

Adapted from Blood Brothers: The Story of the Strange Friendship between Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill by Deanne Stillman

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.