Every year around Valentine's Day millions of almond trees begin to bloom in an expanse of more than 800,000 acres stretching from Sacramento to Los Angeles. In the following weeks more than 30 different varieties of almond trees unfurl five-petaled white and pink flowers at different times. At the center of each flower a cluster of thin pollen-tipped stalks known as stamens surrounds a pollen-catching stigma. In order to produce nuts, an almond tree's flowers must receive pollen grains from a different type of almond tree. Mature flowers on any given tree are only receptive to pollination for five days. If almond farmers want their trees to produce as many nuts as possible, they cannot rely on wind alone to spread pollen, nor are there enough native insect pollinators like beetles and bumblebees to visit all of the 90 million trees during the two-week bloom. Such a Sisyphean task requires a massive army of a foreign pollinator that Americans depend on more than any other: a single domesticated species, without which the U.S. would effectively lose one third of all its crops, including broccoli, blueberries, cherries, apples, melons and lettuce.

Between October and February they come to California from all over the country, riding inside more than one million boxes loaded onto thousands of tractor–trailers. Workers maneuvering forklifts stack the boxes on the trucks in the dead of night, when the containers' residents are all home. They drape nets over the boxes to catch any curious scouts and begin the journey. Sometimes the trucks crash, spilling boxes onto the highway and unleashing living swarms that writhe with anger and confusion, but most of the travelers complete the journey safely. Once the trucks reach their destination, workers unload the cargo and open the boxes for the first time in months. If everything has gone well, a typical box might contain 19,200 adult European honeybees (Apis mellifera). If the majority of bees in a colony were not strong enough to make it through the winter—when they hunker down and live off their stores of honey—the number could be much smaller.

In all, more than 31 billion honeybees converge on California’s Central Valley each February to pollinate the almond trees. By the end of the bloom, having gathered plenty of nectar and pollen to feed their colonies, the honeybee population in the orchards may exceed 80 billion. These are the kinds of numbers you need when you're dealing with something like 2.5 trillion flowers, each of which likely requires several visits from pollen-laden bees to produce a nut. Each year, California produces between 50 and 80 percent of all the almonds harvested worldwide; this year California’s orchards are expected to yield 1.85 billion pounds of almonds, which works out to about 700 billion individual almonds. Every almond grows from a successfully pollinated flower, but the bees likely pollinated far more than 700 billion flowers this past spring. An almond tree can only support and nourish so many nuts, so in April and May the trees shed as much as 15 percent of their almonds, depending on the year.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

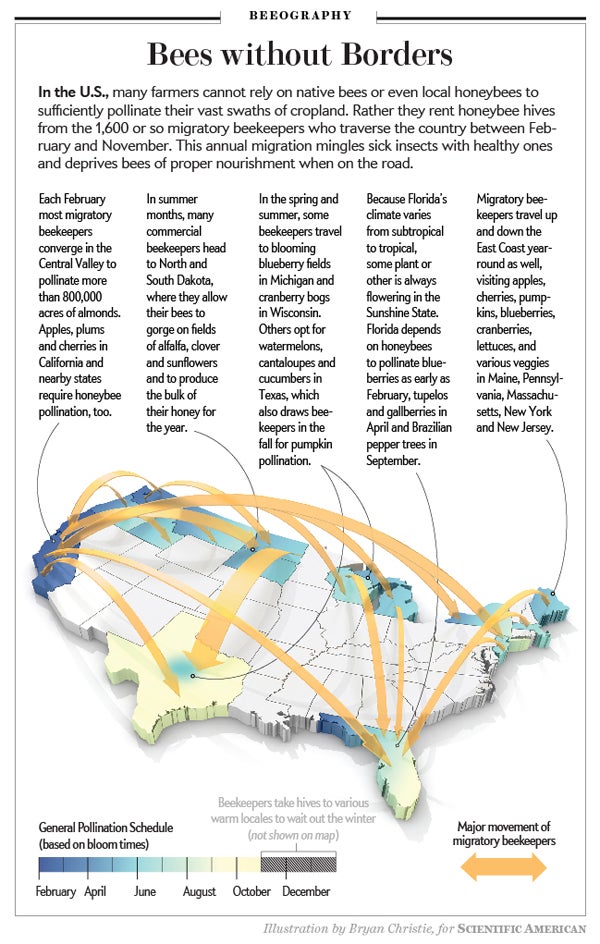

California's almond orchards are the most important stop on a massive annual migration of around 1,600 of the nation's beekeepers and their colonies. Today, many beekeepers make at least half of their annual income not from selling honey, but rather from renting their hives to farmers to pollinate crops nationwide. After the almond bloom some beekeepers take their honeybees to cherry, plum and avocado orchards in California and apple and cherry orchards in Washington State. Come summer time, many beekeepers head east to fields of alfalfa, sunflowers and clover in North and South Dakota, where the bees produce the bulk of their honey for the year. Other beekeepers visit squashes in Texas, clementines and tangerines in Florida, cranberries in Wisconsin and blueberries in Michigan and Maine. All along the east coast migratory beekeepers pollinate apples, cherries, pumpkins, cranberries and various vegetables. By November, beekeepers begin moving their colonies to warm locales to wait out the winter: California, Texas, Florida and even temperature-controlled potato cellars in Idaho. The bees stay inside their hives, eating the honey they made in the summer and fall. Several decades ago beekeepers could let their colonies overwinter in a place as cold as Minnesota without worrying about too many bees dying. That's no longer true; in the past 10 years, many American beekeepers have lost between 30 and 60 percent or more of their hives each winter.

Some researchers, beekeepers and journalists have argued that migratory beekeeping is one of the primary reasons that so many bees die each winter as well as an explanation for colony collapse disorder (CCD)—the sudden and mysterious disappearance of an entire hive's residents, save for the queen and a few stragglers. Bringing so many bees together all at once in Central Valley and other flowering sites guarantees that they will spread viruses, mites and fungi to one another as they collide midair and crawl over each other in the hives. Forcing bees to gather pollen and nectar from vast swaths of a single crop deprives them of the far more diverse and nourishing diet provided by wild habitats. The migration also continually boomerangs honeybees between times of plenty and borderline starvation. Once a particular bloom is over, the bees have nothing to eat, because there is only that one pollen-depleted crop as far as the eye can see. When on the road, bees cannot forage or defecate. And the sugar syrup and pollen patties beekeepers offer as compensation are not nearly as nutritious as pollen and nectar from wild plants. Scientists have a good understanding of the macronutrients in pollen such as protein, fat and carbohydrate, but know very little about its many micronutrients such as vitamins, metals and minerals—so replicating pollen is difficult.

If migratory beekeeping contributes to CCD and honeybee deaths in general, it is likely one of many different causes: Pesticides that linger in plant tissues and weaken the bees' immune systems, tenacious varroa mites that suck out the bees' vital fluids, drought and reduced genetic diversity are also partially responsible. Any one of these threats alone would worry beekeepers; together, they have many crying crisis. And if the beekeepers are that concerned, everyone in the U.S. should be too: as honeybee colonies collapse, so will our agricultural system.

For Scientific American’s special issue on food, Hillary Rosner wrote about one way researchers are trying to lessen honeybees’ workload and save the crops that depend on them: recruiting some major assistance from the thousands of native bee species buzzing about the country: There are blueberry bees that vigorously vibrate their flight muscles to shake pollen free from blueberry flowers; there are cuckoo bees that, like parasitic cuckoo birds, lay their eggs in other bees’ nests; there are plump carpenter bees that burrow in dead wood; metallic sweat bees attracted to the salt in human perspiration; and solitary mason bees that build nests from soil and leaves.

Before European colonists brought the honeybee to America, native bees alone pollinated all the wild flowering plants and the crops grown by indigenous peoples. Of course, that was before we replaced so much diverse habitat with monoculture. With fewer places to live and less to eat, native pollinators have been declining. Now some scientists hope to make our farms appealing to native pollinators and dramatically increase their numbers. The more native bee species pollinate our crops, the less we depend on honeybees, which means less migration and less disease spreading; the more wildflowers we sow, the more both native bees and honeybees have to eat. It all adds up to healthier bees. Farmers can restore wild habitat by planting a mix of native flowering shrubs on fallow fields near croplands for around $600 per acre. Scientists have shown that such newly planted wild habitat attracts native bees, which increases crop yield by 10 to 15 percent and makes honeybees themselves more efficient pollinators. And the increased yield is high enough for farmers to recoup the cost of setting up new habitat in a few years’ time. Now that’s the kind of math that could save the bees—and our food.

Almond pollination math

California’s Central Valley has 810,000 acres of almond trees with an average of 112 trees per acre according to the latest data (pdf) from the U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). That comes to 90,720,000 trees in all.

On average, each almond tree yields around 7,000 almonds, each of which comes from a successfully pollinated flower. Researchers and growers estimate that about 25 percent of a tree’s flowers turn into almonds, which means each tree has about 28,000 flowers.

28,000 flowers per tree X 112 trees per acre = 3,136,000 flowers per acre

3,136,000 flowers per acre X 810,000 acres = 2,540,160,000,000, or 2.54 trillion, almond flowers in the Central Valley.

The USDA estimates that California will produce 1.85 billion pounds of almonds in 2013. Each individual almond weighs at least 1.2 grams.

1.85 billion pounds = 839,145,884,500 grams ÷ 1.2 grams = 699,288,237,083, or about 700 billion almonds.

That means honeybees successfully pollinated at least 700 billion almond flowers, which is almost one third of the total 2.5 trillion flowers in the orchards. The bees likely pollinated quite a bit more than 700 billion flowers, however. Almond tree expert Joe Connell of the University of California Cooperative Extension explains that each tree can only support and nourish so many nuts. In the spring, the trees shed between zero and 15 percent of their almonds, depending on how thoroughly they were pollinated.

If each of the 810,000 acres of almond trees in California receives two hives—the recommended minimum—then the orchards host 1,620,000 hives total each February. About 400,000 of those colonies are from California; the remaining 1,220,000 come from other states. Depending on their size, tractor–trailers can fit between 200 and 400 colonies, so transporting all those out-of-state bees to California would require between 3,050 and 6,100 trucks.

In 1985 entomologists Michael Burgett and Intawat Burikam of Oregon State University anesthetized honeybee colonies with carbon dioxide in order to count and weigh the adult bees. They determined that, on average, an eight-frame hive contains 19,200 adult worker bees (2,400 bees per frame). Based on these numbers, more than 31 billion bees descend on California each February (19,200 X 1,620,000 = 31,104,000,000).

But a colony’s size depends on its overall health and the time of year, among other factors. By the end of the almond bloom, when bees have gathered lots of nectar and pollen to feed new generations, a really booming hive could have up to 50,000 bees, in which case there would be something closer to 81 billion bees in the Central Valley all at once (50,000 x 1,620,000 = 81,000,000,000).

Honeybee expert Eric Mussen of U.C., Davis, thinks many colonies arriving in California in recent years are only about 12,000 bees strong (total population = ~20 billion) and that they each gain only one or two frames’ worth of bees by the end of the bloom, which would increase the population to between 23 and 27 billion.

Foragers make up about 25 percent of a colony, so there would be 4,800 foraging bees in a colony with 19,200 bees, which works out to 9,600 foragers for every acre of almond trees with two hives. Based on research conducted among flowering blueberry bushes by Frank Drummond of the University of Maine and his colleagues, a honeybee forages for four hours and visits 1,200 flowers on average each day. Therefore, 9,600 foragers have the capacity to visit 11,520,000 flowers in one day; the bees in two colonies could make four visits to each of the 3,136,000 flowers in one acre in one day. A single colony would perform half as well, which is still efficient enough to make two visits to each of the three million flowers in an acre in one day; in five days, one colony could visit each flower in an acre 10 times.

If each bee visits only 500 flowers a day, then the bees in two colonies can make only one visit to each flower in an acre in a day and, on its own, a single colony would not be able to visit all the flowers in an acre in one day. But in five days one colony could make nearly four visits to each of the three million flowers in an acre.

How much time bees spend collecting pollen and nectar—and how efficiently they pollinate almond trees in an orchard—depends, however, on a daunting litany of environmental variables, not to mention quirks of bee behavior. If almond flowers are full of pollen and nectar, as they usually are in the morning near the start of the bloom, bees will spend more time on each individual flower, which means less time flying between flowers. Researchers are also uncertain how often honeybees fly between different cultivars of almond trees, which is necessary for pollination, as opposed to sticking to the flowers of one cultivar; it’s also unclear how much bees mingle compatible pollen while rubbing against one another inside the hive, a behavior that makes cross-pollination more likely. Bees are less inclined to emerge from their hives when the temperature drops below 50 degrees Fahrenheit, when winds blow faster than 25 miles per hour, or when it is raining or too cloudy. During the almond bloom even a few days of bad weather can dramatically reduce their pollination efficiency. That’s why many almond growers prefer to rent at least two or more hives per acre. If the weather works against them, the sheer number of bees pollinating on the good days might be enough to make up for the lost time. The outcome of this strategy is the largest managed pollination event anywhere in the world.