Free Black Thought

Campus Week: The case for heterodoxy in views on race

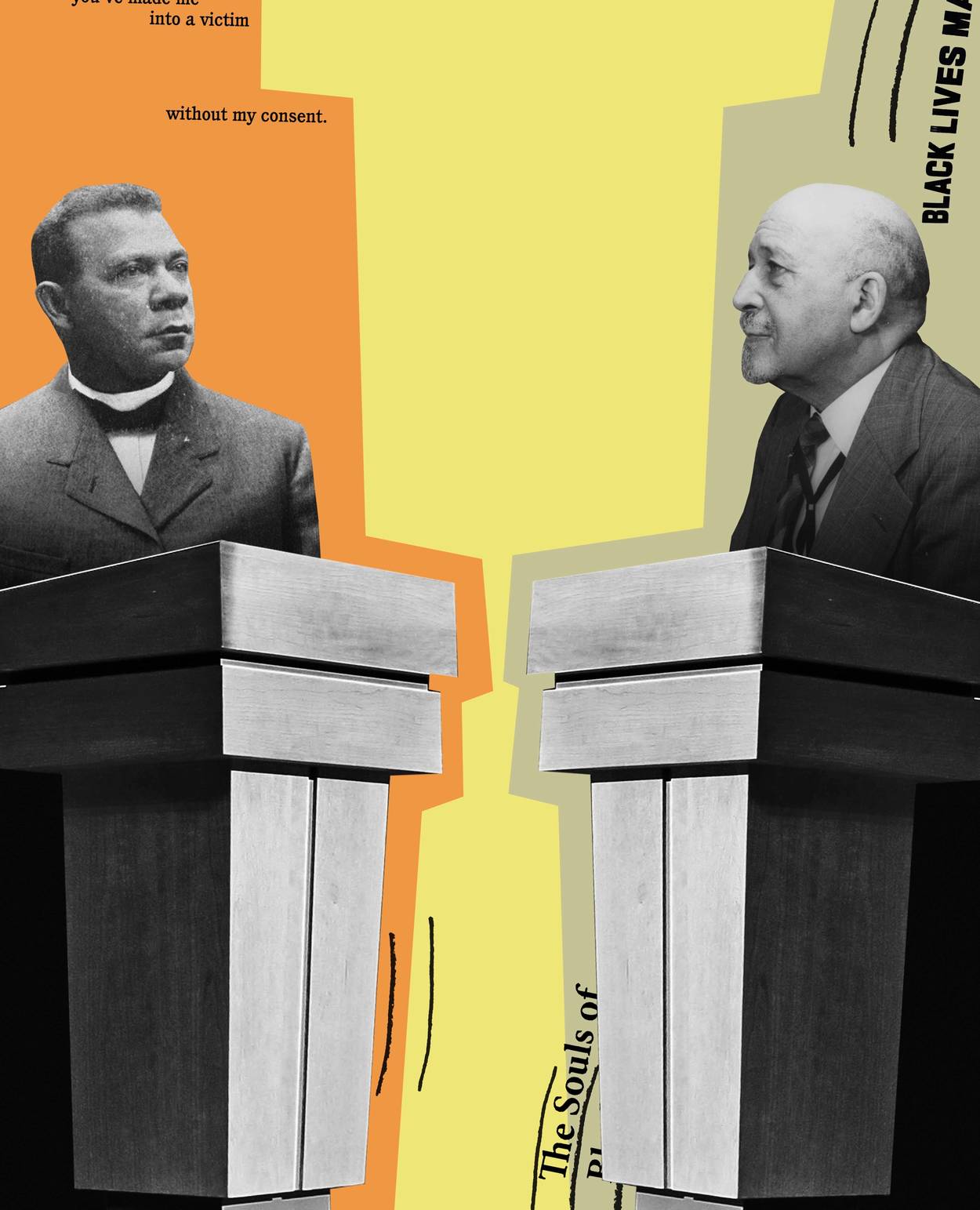

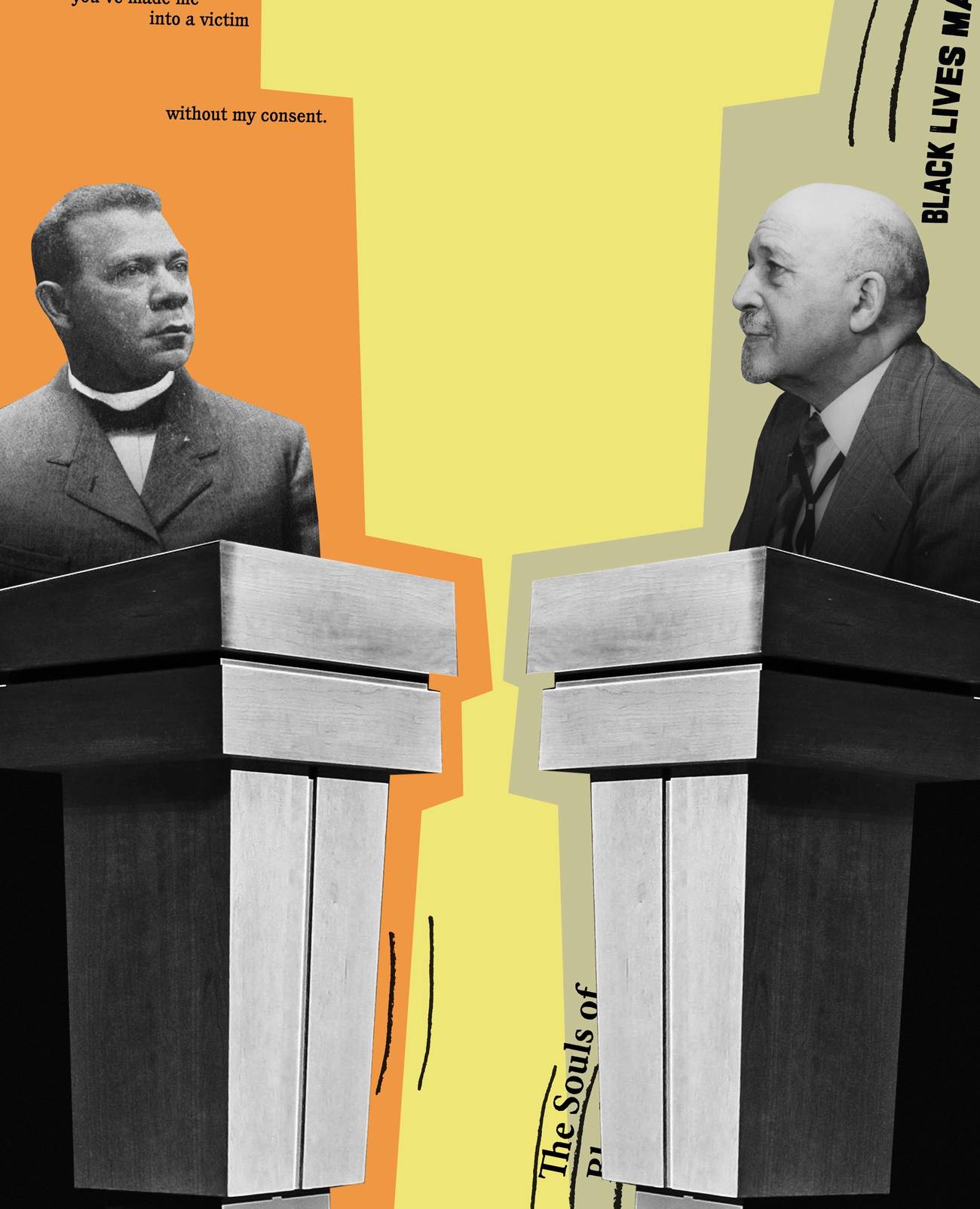

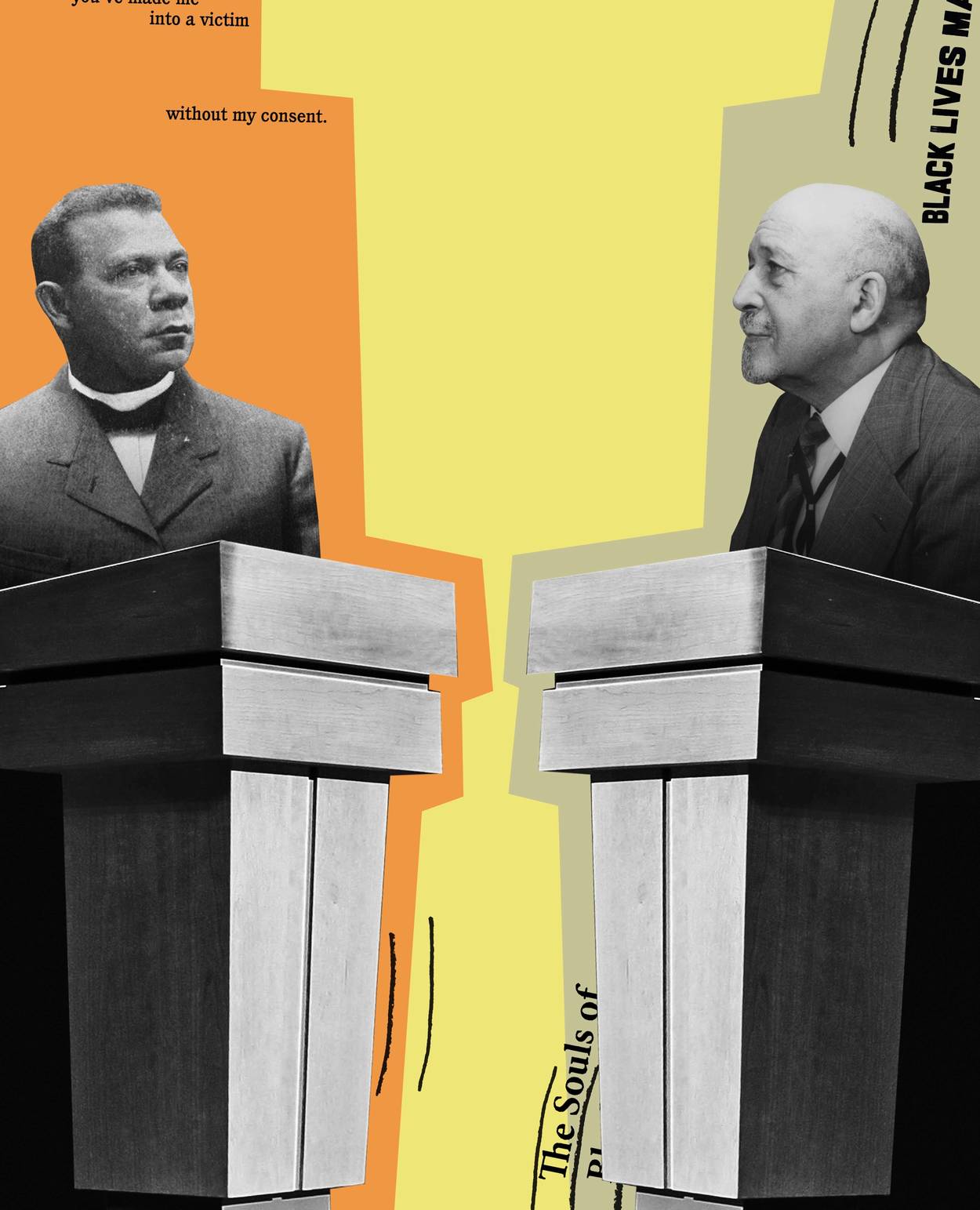

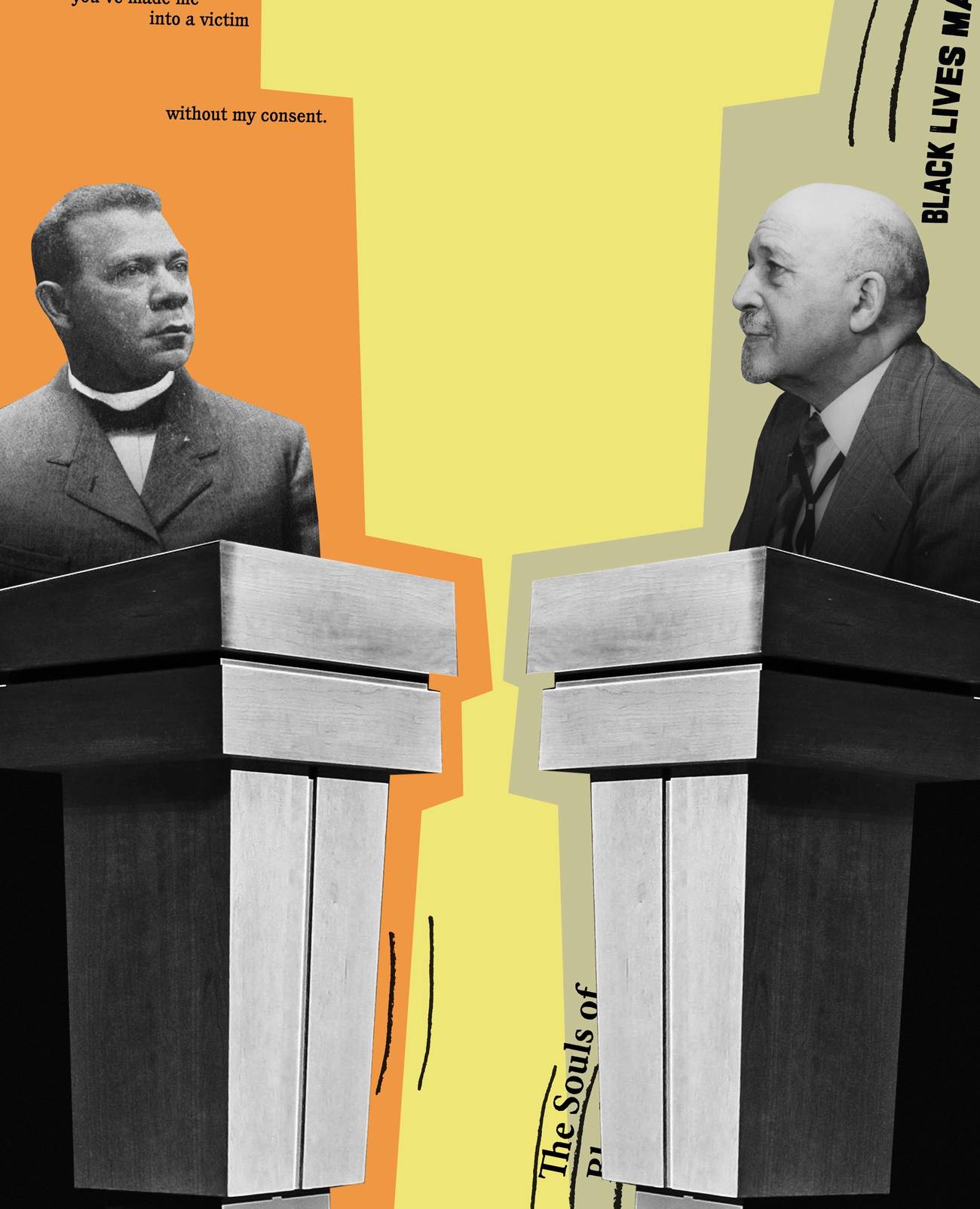

We’re more than 20 weeks into the COVID-19 pandemic and 75 days post-George Floyd. While the street marches for justice have not ceased, and conversations on virtual platforms and social media have proliferated, the genesis of the current conversation within the Black community goes back more than 100 years to the famous debates between the educator Booker T. Washington and sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois three decades after the Emancipation Proclamation. Both men publicized their ideas on how to strive for racial deliverance, but their visions sought opposite directions.

In his famous Atlanta compromise address, Washington advocated that the Black community should accept the inevitable racial barriers they’d face. Progress and privileges, Washington believed, would come as “a result of severe and constant [hard work] rather than of artificial forcing,”—which is to say, demanding obligatory apologies and spiritual transformations inadvertently keeps Blacks subordinate to whites rather than establishing the foundation for both groups to be peers.

Du Bois opposed Washington’s position. A proponent for combating racial oppression through activism, he held the U.S. government responsible for legislating civil rights and economical repair for the Black community—beliefs that pushed him to co-organize the NAACP. Additionally, these beliefs shaped his celebrated book, The Souls of Black Folks—where Du Bois dedicated a chapter to critiquing Washington’s Atlanta speech, stating, “Mr. Washington’s program practically accepts the alleged inferiority of the Negro races.”

It was around this time when the terms “Black conservatism” and “Black radicalism” were defined—thus constructing a binary division within the Black community that has persisted through the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s and into the 21st century. Let’s jump a couple of hundred years to another debate between two other black men: former Atlantic writer and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates and Quillette columnist and philosopher Coleman Hughes. On Juneteenth in 2019, at the U.S. House Judiciary, Coates and Hughes testified on H.R. 40—a bill for reparations.

Coates championed the bill stating, “The method of cultivating this asset was neither gentle cajoling nor persuasion, but torture, rape, and child trafficking.” He believed the implications of American slavery are not only historical but present within “vagrancy laws, red-lining, racist GI bills, poll taxes, mass incarceration.” The federal government was responsible for ills within the Black community since the nation’s wealth is “simply complicit in it.”

Coleman Hughes argued back, believing reparations would be “condescending” to all Black Americans—especially the 33% that polled against the bill. He stated, reparations “would insult many Black Americans by putting a price on the suffering of their ancestors,” and “will make one-third of the Black community victims without their consent.” Likening Booker T. Washington, Hughes stressed that H.R. 40, “would turn the relationship between Black Americans and white Americans from a coalition into a transaction—from a union between citizens into a lawsuit between plaintiffs and defendants,” sentiments that Hughes shared in his piece, “The Case for Black Optimism.”

After the congressional hearing, Coates was lauded in the media as the voice of the American Black community: Vox praised his testimony, calling it a “history lesson” for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. On the other hand, Hughes’ testimony was deemed ignorant and even “anti-Black”—where Rae Sunni, a Black columnist and comedian, tweeted, “Coleman Hughes is arguing against reparations. He’s Cooneman Hughes.” Hughes continues to be the object of ad hominem attacks today, while Coates remains the champion of the trial.

Except, there’s a major contradiction here. We, as Black Americans, dislike being stereotyped based on our color. Isn’t pigeonholing a person based on their skin color the definition of anti-Black? Shouldn’t the community protect the right to diverse thoughts? Furthermore, wouldn’t that diversity help destroy the stereotype that Black Americans are monolithic?

There’s a difference between millions of minds attached to a thought versus millions of thoughts critically agreeing with an idea. This isn’t to say that Coates’ testimony wasn’t valuable and true because it also was popular. It’s to say, his testimony shouldn’t be considered impeccable or universally representative based solely on its popularity. In the same vein, Hughes’ testimony should not be disregarded because his position was anomalous.

I remember watching the congressional hearing at New York University where Ta-Nehisi Coates teaches—and where he formerly taught me. I also remember hurling racial epithets at Hughes, calling him a “coon” as I applauded Coates’ pro argument. I don’t regret cheering for my former professor. But I do regret opposing Hughes without considering his argument. After rewatching the debate, about 20 times, I still see Coates as eloquently accurate; but I also view Hughes as controversially truthful. Even more importantly, I realized that if I disagreed with either, my analysis should critique their argument, not denigrate their identity.

And since we’re on the subject, I would like to briefly discuss cultural critic Thomas Chatterton Williams. After reading his Atlantic piece “Unraveling Race,” and his New York Times op-ed against Coates, and attending his talk on Self-Portrait in Black and White: Unlearning Race at New York University, I was not his biggest fan. During grad school, I wrote a vicious polemic about Williams. Instead of criticizing his ideas on race, I attacked Williams’ racial identity—writing something like:

Thomas is black, and Thomas is white, but Thomas is light. Thomas is, in fact, closer to white. And with the addition of his white wife, his light children, the “bright” aesthetic of his life—perhaps, that’s why he can write, “What Mr. Coates has lost sight of, is the fact that so long as we fetishize race, we ensure that we will never be rid of the hierarchies it imposes.” I am concerned, that Thomas, and other blacks who unjustly convict black people—they are indeed “coasted into hounds” not only at their brothers’ heels but also at their own.

A reassessment didn’t make me a sudden admirer. But I think it’s proper to go after Williams’ concepts, not Williams’ identity as “Black” or his freedom to think or write what he believes. This year, he spearheaded “A Letter on Justice and Open Debate” in Harper’s—a piece that fought to protect writers, journalists, and critics’ “right” to use the First Amendment. A letter with over 150 signatories, a letter I shared on Facebook.

Now, don’t get me wrong. Some Black people do consider themselves “anti-Black” and proudly despise their race. Their fictional avatars might be Stephen Warren—the fictional nemesis of Django Unchained, or Ruckus from the Boondocks, the self-identifying “Caucasian” that suffers from “reverse vitiligo.” It doesn’t take much imagination to understand these characters are real somewhere. Still, they are drastically different than, say, Terry Crews or even Kanye West—a Black individual who holds “unorthodox” or polarizing views.

Let’s jump back in history, and revisit the moment when Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X met for the first time. They both were at Capitol Hill witnessing the derivation of the civil rights legislation before it was passed years later in 1964. After the Senate’s hearing, a brief encounter occurred facilitated by Malcolm’s friendly approach to King. Before this day, both King and X declared disapproval of the other’s tactics. Malcolm X was quoted, saying King is “a 20th-century Uncle Tom,” for his nonviolent approach to racial injustice. At the same time, King considered X’s “by any means necessary” method “dangerously radical,” stating, “urging Negroes to arm themselves and prepare to engage in violence can reap nothing but grief.”

But that brief exchange in Washington, D.C., subtlety changed each man and modified the trajectory of their movements. Malcolm’s rhetoric “softened”—as he later wrote, “I was no less angry, but at the same time, I recognize that anger can blind human vision. “King’s tone became bolder, adapting some of X’s unabashed nature to shake up the nation for equality—which helped when King opposed the Vietnam War and spoke out against the poverty plaguing the Black community.

Neither King nor Malcolm X transformed their viewpoints to match the other’s. Instead, they considered the other’s point of view

Diverse opinions about dismantling systemic oppression aren’t inconvenient stumbling blocks. They can be essential stepping stones. Let’s suppose that W.E.B. Dubois, Booker T. Washington, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Coleman Hughes are neither incorrect nor spot on. Suppose instead, they’ve simply offered up four different ways to inspect racial barriers—or even four different ways to attain liberation as a Black individual.

What if historical and contemporary critical thinkers, whether considered as “conservative” or “radical,” like writers James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Thomas Chatterton Williams, and Maya Angelou; or journalists, like Ida B. Wells, Gwen Ifill, Max Robinson, and Ta-Nehisi Coates; or economists, like Thomas Sowell, Phyllis Ann Wallace, and Walter E. Williams; and philosophers, like Coleman Hughes, Abram Lincoln Harris, and Fanon Frantz; or educators, like Cornel West, Angela Davis, W.E.B Dubois, and Booker T. Washington; and activists, like Fanny Lou Hamer, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and John Lewis—what if each of them, and the millions of other unknowns, were human beings who experienced and analyzed America’s race problem from different angles, and spoke their own truths, which may contain valuable answers to our current problems?

And what if the answer to our century-old question, “Where do we go from here?” can be resolved by considering what they’ve already offered up?

Four hundred years ago, everyone mentioned on the above list would’ve been murdered, because books and pens were criminalized in our ancestor’s hands. These laws weren’t only used to take hostage their ability to read and write, but to keep independent thinking captive. Literacy was a fatal crime, because once a slave could critically think they became dangerous, and therefore were better off dead. A literate slave could easily construct an argument justly opposing their captivity even against a manipulated doctrine proclaiming they weren’t human. And this is why I make a case for Black freedom of thought—an unconditional stance no matter if the next idea challenges mine.

Brittany Talissa King is a freelance writer and journalist.