We live in an e-commerce utopia. I can call out orders and my demands are satisfied through an automated, seamless transaction. I just have to ask Alexa, or Siri, or one of the other digital assistants developed by Silicon Valley firms, who await the commands and manage the affairs of their human bosses.

We’re building a world of frictionless consumerism. To see the problems with it requires you to stop and think, which itself runs against the grain of this technology. Utopia is in the eye of the beholder. One person’s utopia is another’s dystopia. Take the obese humans in Pixar’s Wall-E: never having to move from their mobile chairs with screens they use to get their food delivered to them. The point is not that Alexa will make us obese. Rather, it’s that intelligent technology can manage much more than isolated purchase orders of books, or the devices and systems in our homes. It can manage our lives, who we are and are capable of being, for better or worse.

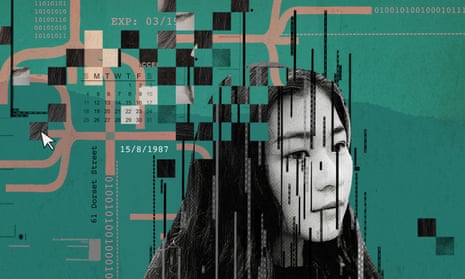

Silicon Valley’s pursuit of frictionless transactions in our modern digital networked environment is relentless. It has given rise to surveillance capitalism – the extraction and monetisation of our data – and the creeping use of such data to “scientifically” manage most facets of our lives, in order to efficiently deliver cheap bliss and convenience.

Yet there is much more to being human than the pursuit of such shallow forms of happiness. Flourishing human beings need some friction in their decision-making. Friction is resistance; it slows things down. And in our hyper-rich, fast-paced, attention-deprived world, we need opportunities to stop and think, to deliberate and even second-guess ourselves and others. This is how we develop the capacity for self-reflection; how we experiment, learn and develop our own beliefs, tastes and preferences; how we exercise self-determination. This is our free will in action.

We don’t want too much friction, either: it is, after all, costly. Paralysis by analysis is a frightening prospect. It’s easier to abandon such deliberations and accept defaults, often set by others. The insights from behavioural economics tell us we choose not to choose. This convenient “choice” is only made easier in our modern data-rich economy.

Consider, for example, Facebook users’ relationship with Facebook. The relationship begins when users click through to Facebook’s sign-up page, which forms a binding legal contract and authorises Facebook’s extensive data collection and sharing practices. The transaction costs are minimal. Trust is essential. Yet it is and has been unwarranted. As the recent Cambridge Analytica debacle highlights, Facebook has enabled third parties – and there are many – to use Facebook users’ data to develop sophisticated psychological profiling and personalisation algorithms, to influence their beliefs and votes. In the end, the debacle is merely a symptom of a diseased digital networked environment optimised for frictionless data flows, advertising and e-commerce.

Some digital tech cheerleaders like to describe data as “the new oil”, the raw material that will drive economic growth. But data is oil-like in more than one way: it eliminates friction and has the potential to re-engineer the environments within which we live – our workplaces, schools, hospitals and homes – so we risk becoming increasingly predictable and programmable.

Consider a simple example. Modern electronic contracting often depends on a seamlessly designed human-computer interface that creates a binding contract through the simple act of clicking or tapping a virtual button. Some economists celebrate this mechanism for minimising transaction costs and eliminating friction in the formation of a contract.

This view is dangerously myopic. It focuses on efficiency gains and ignores subtle but powerful impacts on human autonomy. It makes it rational for a user to blindly accept terms of use. To read the terms would be a waste of time, an irrational and futile exercise. Even if you’re a glutton for punishment, how would you choose which e-contract is worth the time and effort? After all, you enter into so many of them, and they’re spreading like wildfire, from apps and smart TVs to all the devices in your workplace, car and home that are destined – according to e-commerce gurus – to be integrated into the Internet of Things. So people just default to clicking “I agree”. This is not only a predictable response, it is arguably a programmed one.

Frictionless e-contracting makes a mockery of contracting, which is premised on parties genuinely exercising their autonomy when deciding to enter into a binding legal relationship. At best, it generates the illusion of consent through automatic and even programmed behaviour. Repeat interactions with this and other similar mechanisms risk habituation to mindless clicking.

One response to this social dilemma is to deliberately engineer friction into modern consumer choices – to design transaction costs into technology. How should we do this? Too much would probably cause the digital economy to grind to a halt. It needs to be more a case of introducing some digital speed bumps that prompt consumers to slow down and think about the transaction they’re about to undertake in a way that preserves their autonomy. Ways of doing this include courts refusing to enforce automatic contracts and requiring evidence of actual deliberation by consumers about the most important substantive terms of a contract. Software could require a user to scroll over the most important terms and conditions before clicking the “I agree”, or it could even require consumers to answer substantive questions about the contract.

Technology enthusiasts celebrate the idea of frictionless commerce in the home with no trace of second thoughts. Consumers like instant gratification and convenience. And, of course, it’s super-exciting for the marketing folks just waiting to nudge people to make purchases.

But how will such seemingly perfect transactional efficiency affect how we behave in our own homes? How might it impact our willpower? Psychologists have shown that if we anticipate feelings of regret, that can moderate our behaviour in the face of temptation. But to what degree does anticipated regret depend upon the opportunity to reflect upon one’s preferences? As convenient as it may be, we should worry about technology creating a consumer world without friction.

- Brett Frischmann is the Charles Widger endowed university professor in law, business and economics at Villanova University, Pennsylvania, US, and an affiliated scholar of the Center for Internet and Society at Stanford Law School. His book, Re-Engineering Humanity, will be published on19 April