Among the political figures who congratulated Donald Trump on his surprise election victory was the politician to whom the billionaire real estate mogul and reality television star has most often been compared: Silvio Berlusconi.

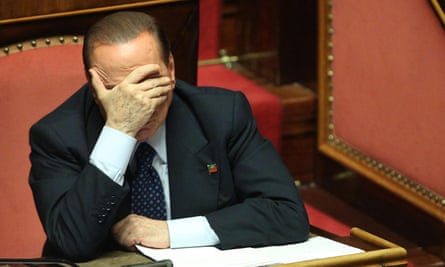

The rightwing former Italian prime minister and billionaire media mogul, who was dogged by claims that he used an underage prostitute at his infamous “bunga bunga” parties and counted Vladimir Putin as a close ally and friend, said the comparisons between the two were “obvious” and that Trump would rule with “authority and equilibrium”.

If it’s true that Berlusconi and Trump, two showmen who have railed against immigrants, mocked women and targeted press freedom, are indeed cut from the same cloth, it may also be the case that few will understand liberal Americans’ consternation in coming years like the Italians.

Here, then, are some warnings – and a few words of advice.

Political opposition: ‘Stop crying and try to understand his voters’

For years, Berlusconi’s boorish behaviour was a gift to political opponents and journalists who were free to ridicule him. But ultimately they did not prove an effective opposition.

“Berlusconi’s opponents had a very wide and open avenue and they couldn’t resist walking down that avenue. This brought them to a number of defeats. Because when he said: ‘The west is [superior]’, and opponents said: ‘How politically incorrect, white imperialist’, the reality is that a huge part of the Italian voters said in private: ‘He is right,” said Giovanni Orsina, author of Berlusconism and Italy, an exploration of how Berlusconi held on to power.

Opposing Berlusconi by ridiculing him, Orsina said, was a way to preach to the converted, as were attempts to warn that Berlusconi’s rule represented the end of Italian democracy.

“The most powerful way to oppose him, but it was never really done seriously, was to try and understand what his voters want and try to address the need of his voters. No jokes, stop shouting, stop crying, stop saying: ‘It is a horror and disaster’; try and seriously understand what his voters want, and the left was never really successful in doing that,” Orsina said.

Press freedom: journalists ‘must be wary of complicity’

Trump has made no secret of his disdain for the media, having promised during his campaign to “open up our libel laws” to make it easier to sue media organisations for damages – singling out the New York Times, CNN, and the Washington Post, among others – and promising: “If I become president, they’re going to have such problems.”

Berlusconi’s rise in Italy was inexorably linked to his control of the media. He not only exerted influence over state-controlled organisations through his role as prime minister, but through his own media empire, including a major broadcaster and publishers.

“Many journalists were complicit even without being controlled, for example by accepting conditions, or when he chose journalists he preferred for interviews,” said Jacopo Iacoboni, a political journalist at La Stampa.

In what was later called “the Bulgarian edict”, Berlusconi in 2002 accused journalists at state-controlled RAI of using “television as a criminal means of communication”, in part because of reports that alleged Berlusconi had ties with organised crime. The journalists were subsequently fired and banned from working for RAI.

Everyday sexism: prepare for a new feminist fightback

Berlusconi was ultimately acquitted of knowingly hiring an underage prostitute at his infamous “bunga bunga” parties, and of abusing his position to cover it up. But his tenure became synonymous with the everyday demeaning of women – particularly on television – as sex objects, as the prime minister regularly insulted and mocked women in public, even making sex jokes at public events meant to honour women’s achievements.

In Berlusconi’s Italy, a woman’s looks were paramount. The prime minister even appointed a former model and showgirl to serve as equal opportunities minister.

Trump’s obsession with women’s looks has similarly been well documented throughout his campaign for president, including his rating women on a scale of 1-10, and numerous accusations of sexual harassment and assault.

But in Italy there was also a backlash, and an awakening among some Italian women, according to Emma Bonino, the former foreign minister and feminist who helped secure abortion and divorce rights in Italy in the 1970s.

“Berlusconi’s attitude prompted a sort of revolt from women, and women’s groups, who had been silent and absent for years, even on important women’s issues,” Bonino said. It prompted opposition to female stereotypes, particularly in the media, and the scourge of domestic violence, which had often gone unacknowledged, she said.

The religious right: an unholy alliance?

Berlusconi had an unspoken agreement with the Roman Catholic church that helped him hold on to power.

Italian bishops looked the other way and did not criticise what might otherwise have been deemed less-than-Christian behaviour, as long as Berlusconi helped them on their legislative agenda, including blocking same-sex unions, limiting fertility treatments opposed by the church, and generally addressing their fear of being “swallowed up by secularisation, Islam [in the form of immigration], and liberalisation”, said Massimo Faggioli, a church historian at Villanova University.

Five years after his resignation from office, Italy still has no prospects of passing same-sex marriage into law (though civil unions are now legal), lesbian and gay parents do not have legal rights over their children, IVF treatment is limited to married couples, and surrogacy – strongly opposed by the church – is illegal.

Similarly, the thrice-married Trump - who has never convincingly spoken of having religious faith – won the support of four out of five white evangelicals, largely based on their hopes that Trump would elect conservative anti-abortion judges on the supreme court. While it has received scant attention, Trump has also promised to repeal a 1954 ban that prevents tax-exempt organisations like churches from getting involved in politics, a change that could give churches an even more powerful role in US politics.

Berlusconi and the law: a worrying precedent

Last week Trump settled fraud lawsuits relating to Trump University for $25m, removing a legal headache despite having pledged to fight the cases to the bitter end.

He has also alleged that he is the subject of an audit by US tax authorities and, before his election, had threatened to sue women who had accused him of sexual harassment and assault.

Berlusconi faced similar entanglements with the judicial system and the issues ultimately pressured him and constrained his ability to pass legislation. Prosecutors who sought to charge him with crimes were derided as unelected communists, and there a poisonous relationship soon developed between judges and prosecutors and the prime minister’s office.

“Berlusconi tried to use his political power to defend himself, making laws and using his position as prime minister to delay trials. There were also several legal attempts – like making a law that as president of the republic you cannot go to trial as long as you are in power – but he never really succeeded,” said Orsina.

Trump enters the White House after a contentious election in which he derided federal investigators at the FBI, but also after he was seen as having been helped by the FBI director, James Comey, who made a surprise announcement about the continuation of a probe into Hillary Clinton – which was later dropped – 11 days before the election. Trump has also sought to delay a civil fraud trial into one of his businesses until after his inauguration.

Minority rights: ‘Migrants were scapegoated for societal decline’

Like Trump, Berlusconi’s rise was fuelled by his anti-immigrant views, particularly against the Roma and, later, migrants. In his final years in office, defections from Berlusconi’s Forza Italia party forced him to look to Italy’s far right – even more than he had before – to keep his coalition, essentially forcing him to lock arms with the xenophobic Northern League, which has called for the expulsion of migrants. A similar dynamic may soon be at work in the US.

While Donald Trump this week called for the deportation of 2 million to 3 million undocumented immigrants who have allegedly committed crimes, he left the door open to even more deportations later on, even as the Republican speaker of the House, Paul Ryan, who is a mainstream conservative, denied there was interest in a “deportation force”. A rupture between Trump and Ryan could force Trump to seek alliances among even more rightwing Republicans on immigration policy.

The position of minorities in Italian society, according to the senator and human rights expert Francesco Palermo, was “affected severely”, in large part due to a series of “emergency decrees” that sought to expel the Roma from Italy. Funds for traditional minorities were reduced and are now 1/10 of what they were in 2000, Palermo said, and migrants “were scapegoated for the overall decline of society”.

“I do not believe minorities will be a direct target under the Trump administration, as this would immediately be under the spotlight. But more worrying, the deterioration of their situation will be a consequence of the societal climate. This is somewhat similar to the trend we observed in Italy under Berlusconi,” Palermo said.

The damage done

Berlusconi did not ultimately vanquish Italy’s democratic institutions. But the lasting damage he inflicted, according to Guy Dinmore, a former correspondent for the Financial Times who covered Berlusconi’s final term, came in the way his three-time premiership celebrated and normalised the flouting of rules, including on paying taxes.

“What he did was to perpetuate the old system he inherited, which was a clientelist system where meritocracy had no place, and corruption is rife, and people were almost encouraged by Berlusconi not to pay their taxes. Italy was a swamp … and he made it worse,” Dinmore said.

Journalist Iacoboni agreed, saying the lasting impact of Berlusconi was “the cultural idea that you could do anything in your own interests.”

“He legitimised every kind of infraction of rules, going back to his television career in the 1980s. It was as if to say: ‘You Italians like to be gross with women? Well, I say to you, you can do this.’ I think this [idea you can do anything to further your own interests] is much worse than even the legal accusations.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion