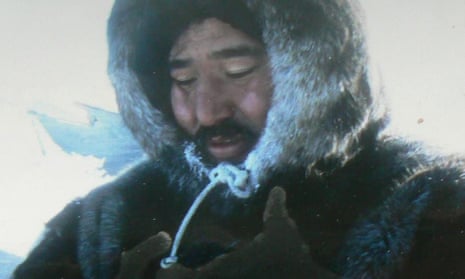

Growing up in the Canadian Arctic, Louie Kamookak was captivated by tales from Inuit elders of rusted utensils strewn along a remote shore and mysterious white men using ropes to haul a large ship through the ice.

Years later, he realized there was a striking resemblance between the stories of his youth and historical accounts of the ill-fated expedition of Sir John Franklin, whose two ships – and 129 crew members – vanished while searching for the North-West Passage in the 1840s.

Kamookak compared Inuit stories with explorers’ logbooks and journals to develop a working theory of where the ships might be.

He shared these thoughts with Canadian archaeologists, and was eventually vindicated in a spectacular fashion when, using his directions, divers located the HMS Erebus in 2014, and two years later, the Terror.

Both ships were found exactly where Kamookak had predicted.

Archaeologists and historians have paid tribute to the Inuit oral historian who helped solve a mystery that had confounded explorers for generations, after he died this week aged 58.

He is survived by his wife, Josephine, their five children and seven grandchildren.

“Louie was someone who devoted three decades of his life to understanding the puzzles and the clues surrounding the disappearance of the two ships,” said John Geiger, president of the Royal Canadian Geographic Society, calling Kamookak “the last great Franklin searcher”.

Born at a seal hunting camp and brought up in nomadic camps for the first decade of his life, Kamookak was long fascinated by stories he heard from elders.

With no written language for generations, Inuit have relied on oral history as a means of preserving knowledge of their surroundings, as well as unique and noteworthy events.

For years, European explorers and historians ignored that oral history, but Kamookak became convinced it was the key to discovering the location of the Franklin shipwrecks.

At least 36 expeditions from 1847 to 1859 searched for Franklin’s lost ships, with dozens more in the 20th century. All ended in failure.

“It’s usually politicians praising traditional knowledge, but not really respecting it completely, or academics using it in order to get entree into communities that really don’t want them there,” said Paul Watson, author of Ice Ghosts: The Epic Hunt for the Lost Franklin Expedition. “Louie showed that traditional knowledge really does mean something.”

In recognition of his “relentless dedication” to showcasing Inuit culture and history, Kamookak was recently appointed to the Order of Canada. He was also a fellow of the Royal Canadian Geographic Society and its honorary vice-president. The Society plans to create a medal in his name, said Geiger.

Kamookak spent much of his adult life in the community of Gjoa Haven, a hamlet above the Arctic Circle, working as a teacher and educating youth about the importance of oral history.

“He was concerned that the stories be passed along to young Inuit and that they wouldn’t be lost,” said Geiger. “He wanted to preserve the wisdom that comes from people who have lived for centuries on the land and understand it innately.”

Until his death, Kamookak remained steadfast in his pursuit of Franklin’s remains. He knew of stories in which Inuit hunters witnessed the burial of a ship’s captain, which Kamookak suspects was Franklin.

“As recently as two months ago he was planning to return to the Arctic this summer and continue his search for the tomb or grave of Sir John,” said Geiger. “He’s someone whose search for understanding of the terrible disaster really never ended. It was with him until the very last days of his life.”